Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. We at Baltimore Heritage cannot say it enough. This year has been challenging for everyone and we could not have navigated it without your support. Our new Five Minute Histories video series and our ongoing Legacy Business and Centennial Homes programs, to name a few, are possible only with your help. If you haven’t yet done so, please consider joining or renewing your membership today.

Here are just a few of this past year’s projects made possible with your support:

We produced over 100 Five Minute Histories videos. Beginning the first day of Maryland’s Covid lock-down, we have traveled all over our city covering topics such as the Civil Rights Movement, mercantile history, immigration, religious development, Native American history, LGBTQ heritage, transportation, landscape design, women’s rights, and even some geology.

We expanded our Friday afternoon history lecture series and went virtual. In partnership with the Baltimore Architecture Foundation, we held engaging talks by Charlie Duff, Nancy Proctor, Jackson Gilman-Forlini, Aaron Henkin, Anne Bruder, Meg Fairfax-Fielding, and more.

We handed out 5 micro-grants and 18 preservation awards virtually. We pivoted to a Zoom pitch party to continue to make preservation a participatory sport with micro grants. Thank you to member Brigid Goody for making this yearly event possible. And we have been featuring our 2020 preservation awards winners on our website and on our YouTube channel.

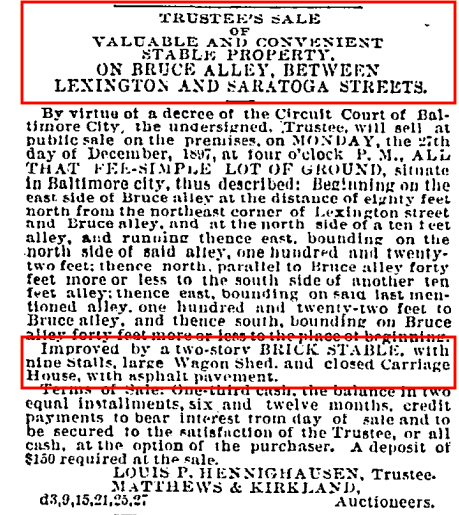

We continued to fight to preserve Baltimore’s heritage. Restoration has begun at the Bruce Street Arabber Stable. Construction continues at the Lafayette Square bathhouses. And the Center for Health Care and Healthy Living at the Baltimore Hebrew Orphan Asylum will soon be 100% occupied by the Baltimore City Health Department and Behavioral Health System Baltimore.

For all of you who volunteer, log-on to our programs, email us kind words (and correct our mistakes), and support our advocacy work in Baltimore, please accept a sincere thank you from all of us at Baltimore Heritage. Your time, talents and financial support make a difference. Please consider joining or renewing your membership.

We wish you a safe holiday season and thank you again for doing so much for Baltimore.

P.S. Need a holiday present idea? Get in touch about how you can get a gift membership for a friend or family-member!