A panel from the Urban Land Institute that Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake engaged around the redevelopment of downtown’s “West Side” recently delivered preliminary recommendations (more from the Baltimore Sun). As the area continues to be in the spotlight and we continue working towards a renewed and revitalized West Side, we thought it would be helpful to provide a short recap of how redevelopment plans that have evolved from early proposals calling for widespread demolition to current plans based on both preservation and redevelopment.

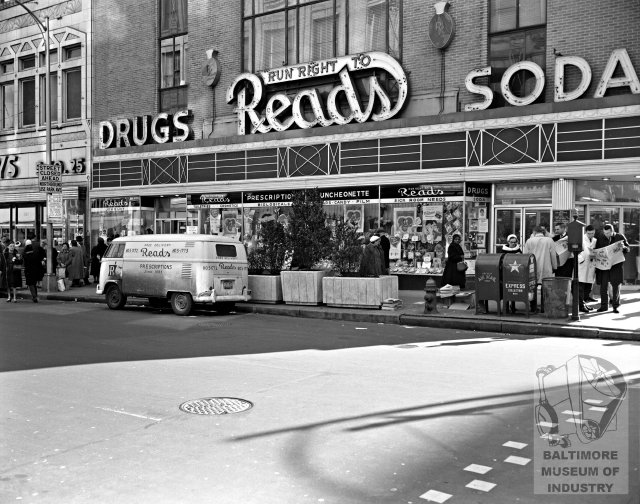

The “West Side” of Baltimore’s downtown is an area roughly bounded by Pratt Street (south), Read Street (north), Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard (west), and Liberty Street/Charles Center (east). From the late 1700s through the 1940s, the West Side grew as a vital center of transportation, commerce, and cultural life. This growth first began with Lexington Market in 1782–a place that inspired Ralph Waldo Emerson to declare Baltimore the “Gastronomical Center of the Universe”– and continued in the early 20th century with the construction of dozens of premiere department stores and movie theaters that many Baltimoreans still remember fondly. Unfortunately, in the late 20th century retail shopping and investment drifted out to Baltimore’s suburbs, many of these businesses closed, and their buildings began to decay from neglect.

View West Side’s Market Center Historic District in a larger map

After years of decline, Baltimore City proposed a plan in the 1990s that took an old-fashioned urban renewal approach to redevelopment and threatened to demolish 150 or more historic buildings (See Baltimore City Council Ordinance 98-333, 1998). In response, Baltimore Heritage and our partner Preservation Maryland developed a preservation based strategy for the revitalization of the West Side (PDF). This strategy proposed focusing new construction on existing vacant lots, rehabbing existing buildings for new uses, and reducing the number of historic buildings slated for demolition. In 1999, the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed Baltimore’s West Side on its annual list of 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in recognition of the threat to one of the best collections of historic buildings in any downtown. In 2000, the National Register of Historic Places listed the West Side as the Market Center Historic District designating hundreds of West Side buildings as significant historic structures.

In 2001 with strong encouragement state legislature, Baltimore City adopted a new preservation-based strategic plan (PDF) and signed an agreement with the Maryland Historical Trust laying out a process for preserving historic buildings and moving forward with revitalization. Many of us celebrated the agreement, which has been in effect in the decade since and continues to guide development today. This agreements supported the rejuvenation of nearly 50 historic buildings, including the rehab of the former Stewart’s Department Store as Catholic Relief Services, the Hippodrome Theatre’s transformation into the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center, and the reuse of a handsome retail block on Franklin Street as St. James Place. These projects and many more reflect hundreds of millions of dollars in public and private investment with substantial support from state and federal historic tax credits. However, the real challenge is that redevelopment has taken much longer than envisioned and much of the area, including the Superblock along Lexington Street east of Lexington Market and the Howard Street corridor, is still characterized by vacant buildings and limited street life.

Most recently, Mayor Rawlings-Blake convened a panel from the Urban Land Institute to provide recommendations to jump-start a new phase of revitalization on the West Side. The ULI panel provided preliminary recommendations on December 10, 2010 and final written recommendations from the ULI panel are due to the Mayor in the spring. In one of their most important points, the panel highlighted the West Side’s historic buildings as the area’s greatest asset. Baltimore Heritage is dedicated to supporting a process that can reestablish the West Side as a great Baltimore neighborhood with a distinctive historic character and thriving street life that can attract residents and businesses from across the city and the nation. Our series continues next week with a discussion on the “Superblock” and how historic Lexington Street–formerly known as the heart of downtown–is at the center of this effort to preserve and revitalize the West Side as a great place for Baltimore.