We are so thrilled to be returning to our regular walking tour programming that we have decided to add even more options! Please check out the following new additions to our tour schedule.

Jonestown & the Shot Tower Jonestown is one of Baltimore’s oldest and most historic neighborhoods. On April 8, we hope you’ll join Baltimore Heritage and tour guide Bev Rosen as we stroll past a series of firsts: the McKim Free School, the city’s oldest education building from 1833, the Lloyd Street Synagogue, the first synagogue in Maryland and the third oldest in the country, and the 1808 home of Charles Carroll, the longest living signer of the Declaration of Independence. And of course, what is a visit to Jonestown without a stop at the iconic Phoenix Shot Tower! Register here.

Maryland Women’s Heritage Center On April 20, join Baltimore Heritage on a special behind-the-scenes tour of the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center with its Executive Director, Diana Bailey! Formerly the Woman’s Industrial Exchange, the third oldest women’s exchange in the country, the building continues to honor Maryland women with art installations and exhibits including the MD Women’s Hall of Fame and “Valiant MD Women: The Fight for the Vote.” Over wine and cheese, we’ll be joined by Dr. Amy Rosenkrans to hear the stories behind the artifacts. Register here.

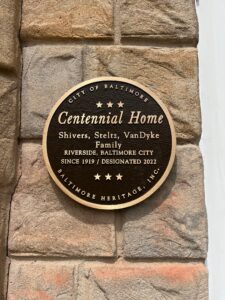

Liberty Ship S.S. John W. Brown On May 17, join Baltimore Heritage on a special behind-the-scenes tour of S.S. John W. Brown, one of only two remaining, fully operational Liberty ships that participated in World War II. One of 384 vessels built at Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard, S.S. John W. Brown could carry almost 9,000 tons of cargo, about the same as 300 railroad boxcars, and could transport every conceivable kind of cargo during the war – from beans to bullets. On May 17, join us to go below deck and explore this preserved piece of history! Register here.

LGBTQ Heritage in Charles Village On June 3, celebrate Pride Month with us on a LGBTQ Heritage walking tour of Charles Village! Guides Richard Oloizia, Louis Hughes and Kate Drabinski will take us on a walk past local landmarks from the original home of the Gay Community Center of Baltimore, now the GLCCB, to the St. Paul Street church that supported the growth of the Metropolitan Community Church, Baltimore’s oldest LGBT religious organization, and the radical feminist writers and publishers that gave a voice to lesbian authors who might not otherwise have been read. We hope you’ll join us to celebrate Pride and the incredible community that called Charles Village its home. Register here.

The Catacombs Under Westminster: Two Hundred Years of Tombs and Edgar Allan Poe’s Gravesite On June 24 and July 15, join us to explore the eerie catacombs underneath Baltimore’s First Presbyterian Church, now called Westminster Hall, and the graves that surround it, including the final resting place of Edgar Allan Poe. The burial ground predates the church, which was built on arches above the gravesites, so that the graveyard and its tombstones lie both underneath and around the building. All told, the compact cemetery next to the University of Maryland School of Law is the final resting place for over 1,000 individuals. We can’t wait to see you “Where Baltimore’s History Rests in Peace!” Register here: June 24 & July 15

We will be updating our tour schedule to include more Behind the Scenes tours of places all over city, so please continue to check our website. Find all of our tours and more here!

– Johns Hopkins, Executive Director

The Baltimore

The Baltimore