Special thanks to Lisa Kraus, volunteer with the Northeast Baltimore History Roundtable, for sharing this guest post on a new preservation issue in the Westfield neighborhood.

Nestled in a tiny patch of woods at the heart of Northeast Baltimore’s Westfield neighborhood, the Christopher Family Graveyard has been all but forgotten over the last fifty years. An unknown number of Christopher family members were buried in the plot sold out of the family in 1962. Over the years, the lot has become overgrown, and only a few neighbors and family members remember that the cemetery is even there. The tombstones that once marked the graves have been displaced, damaged by vandalism, and stolen. Now there is a new proposal by the property-owner to develop the land and place a road where the cemetery still stands.

Family cemeteries like this one pose a unique set of problems not only for the descendants of the people buried there, but for city planners, developers, and neighbors. The state agency that oversees graveyards, the Maryland Office of Cemetery Oversight, does not regulate abandoned cemeteries, family cemeteries, or non-operational cemeteries. Cemeteries are sometimes listed in the National Register of Historic Places if they meet special criteria but small family cemeteries do not generally qualify. Even if they did, listing in the Register does not afford any protection if the land is privately owned. And while these resting places may contain valuable archaeological data, their cultural significance as inviolate places where the dead are memorialized typically takes precedence over any research questions their excavation might help to address.

The preservation threat to the Christopher Family Graveyard highlights questions that often arise when a family burying-place is found unexpectedly on land slated for development. How do cemeteries vanish from official documentation such as land records? How old is the cemetery, who is buried there, and how long was it in use? How many burials might there be, and what can be done to find out? And perhaps most important of all: who decides the fate of this modest family burial plot?

Intensive historical background research can address some of these questions. The Christopher Family Graveyard appears in maps and surveys as late as 1941, but current maps do not depict a cemetery at this location. This appears to be due, at least in part, to the manner in which the land was transferred away from the Christopher family in the early 1960s. The property was foreclosed upon by the City, and subsequently sold to a non-family owner. While our research is continuing, one consequence of the foreclosure and sale by the City was that the subsequent deeds for the property did not mention the cemetery.

Although the foreclosure, makes it difficult to trace the land back using deed research, but with diligence, this obstacle can be overcome. The land records reveal that the Christopher family lived on the land that included the quarter-acre plot set aside for the cemetery from 1773 until the land was foreclosed in 1962. The land parcel was known, in the 18th century, as “Royston’s Study,” and was originally surveyed for John Royston in 1724. John Christopher purchased Royston’s Study, which originally included fifty acres, on July 29, 1773.

The cemetery first appears in a deed dated October 2, 1851, in which all the land, except the quarter-acre containing the graveyard, was sold to John Gambrill, with the following provision:

“reserving, however, the right to access to and egress from the said graveyard, over the land hereby conveyed, to the heirs and relatives of said John Christopher, deceased, at and for the sum of two thousand dollars.”

Although the land was sold, the family of John Christopher (most likely the son of the John Christopher who originally purchased of the land) paid the Gambrills for the right to access the family plot, which remained in their possession.

The following year, Elijah Christopher bought back a little more than two acres of the family property. According to the 1860, 1870, and 1880 federal census, Elijah worked as a wheelwright and carriage maker, an occupation that undoubtedly benefited from the property’s location fronting on Harford Road (known then as the Baltimore and Harford Turnpike). Elijah and his family remained on the property, and likely handed it down through the generations until 1962. Elijah appeared as the owner of the parcel on G.M. Hopkins’ 1877 Map of Baltimore.

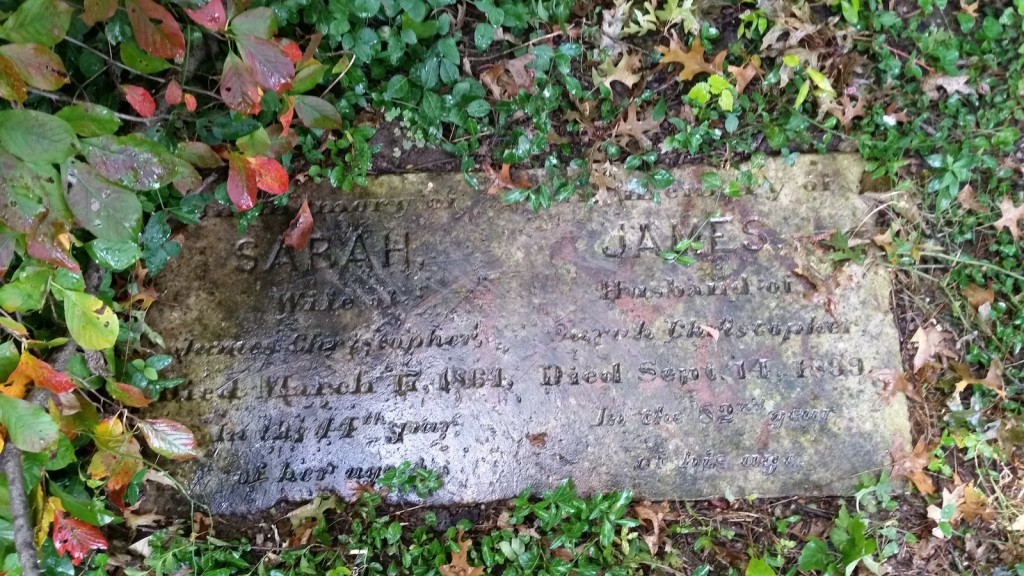

That the cemetery exists is not only demonstrable through an examination of land records; one headstone remains on the plot, that of James and Sarah Christopher. James’ date of death is listed as 1899.

Without conducting a careful excavation of the cemetery and the area immediately surrounding it, it is impossible to know the number of burials that may be present. Although the fact that the quarter-acre plot was reserved in the 1851 deed of sale suggests that the burials could be confined to that one parcel, the family had occupied the land for almost eighty years by that time. It is possible, even likely, that burials exist outside the known cemetery boundaries.

As for what will become of the little cemetery, that has yet to be seen. Human remains, gravestones, monuments and markers may be removed from an abandoned, private cemetery, if the removal is authorized by the local State’s Attorney. State law then requires remains and any markers to be placed in an accessible place in another cemetery.

In addition, cemeteries can be sold for other uses if a court decision is made in favor of redeveloping the land. The court generally requires the proceeds from the sale of the land to be used to remove all human remains and monuments from the property. When a judgment for the sale of a cemetery for use for another purpose has been entered, the buyer of the cemetery receives the title to the land free of the claims of the owners of the cemetery and of the holders of burial lots in the cemetery.

Was this issue the subject of the 1965 court case? Have the burials already been removed? If so, these facts remain to be documented, and it seems unlikely, since several current neighbors remember more monuments being present as recently as ten years ago. The descendants of the Christopher family who still live in the area have a variety of preferences concerning the development of the land, but all agree that at a minimum, they wish to ensure that their ancestors’ graves are either avoided by the proposed development, or else moved before a cul-de-sac is constructed over the cemetery parcel.