Our latest post in our ongoing series on the 100 year history of Guilford is by Walter Schamu FAIA on the role of Edward L. Palmer. Enjoy Walter’s thoughtful history of Palmer and his firm Palmer & Lamdin:

It would be impossible to discuss the history of Baltimore’s Guilford community without serious attention being given to the architect Edward L. Palmer. Palmer and his firm of Palmer and Lamdin designed many of the significant residences in Guilford, as well as Roland Park, Homeland and Gibson Island.

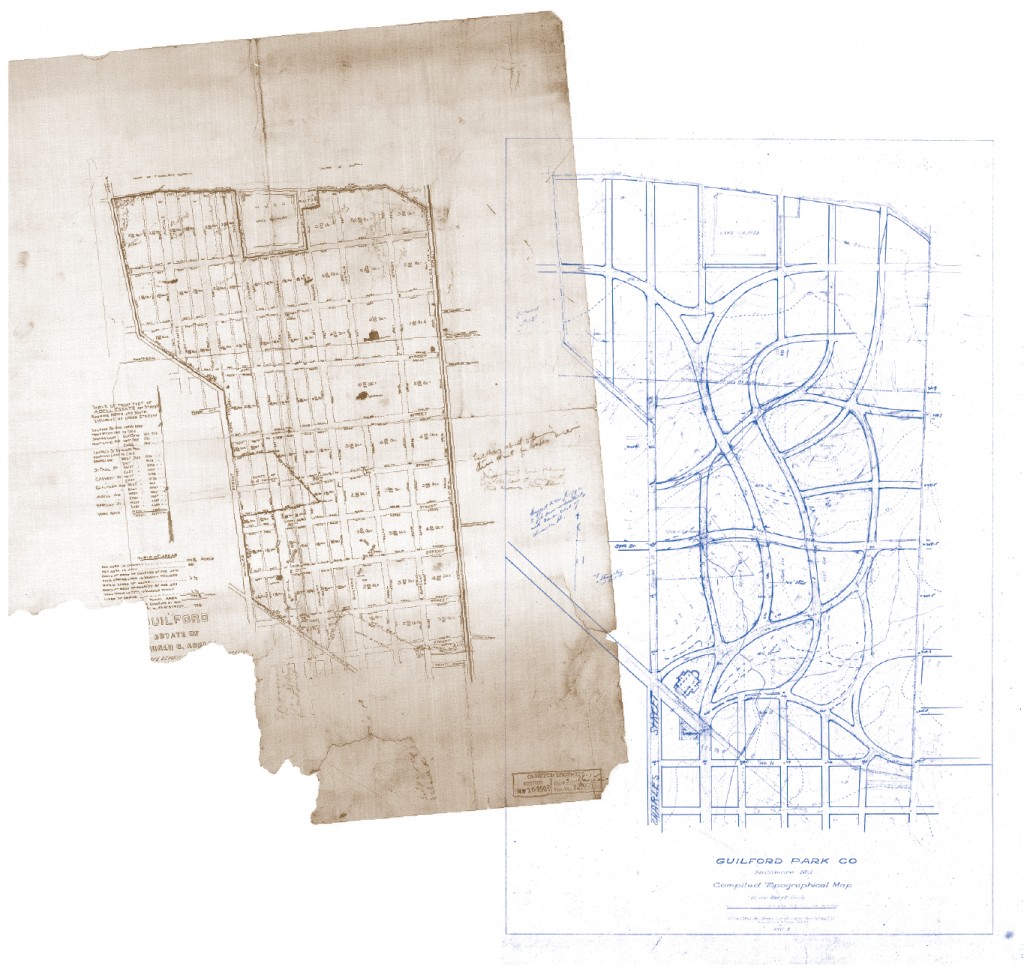

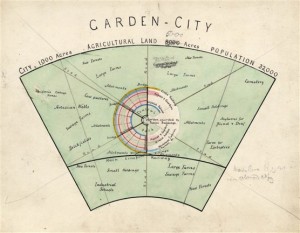

Edward L. Palmer was an 1899 graduate of Johns Hopkins and, in 1903, the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture. He began his career in architecture as the in-house architect to the Roland Park Company working for Edward Bouton, the developer of the new planned Roland Park community and Guilford. During the time as architect for the Roland Park Company he designed some of the first Guilford homes including the greatly admired Tudor Revival Bretton Place and Chancery Square (1913).

It was once reported by Palmer’s daughter, Ann Sinclair-Smith, that Bouton sent young Mr. Palmer to Switzerland to see, first hand, how houses can be constructed on steep slopes. No doubt this was to prepare him for the “unbuildable” terrain of much of northern Roland Park. In 1911 Palmer and Bouton traveled to Europe together looking for ideas and studying domestic architecture. In 1917 he left the Roland Park Company and began his firm as “Edward L. Palmer Jr. Architect.”At this point begins the story of a truly remarkable architectural firm which, through its many iterations, designed over 200 residences and hundreds of institutional, religious and corporate buildings in the Maryland region and beyond.

As quoted in Mr. Palmer’s obituary in the Baltimore Sun, October 27, 1945:

“It was during the period from 1907 to 1917, when he served as architect and a member of the Committee on Approval of Plans for the Roland Park Company, that Mr. Palmer’s work in residential development earned him national recognition among architects and real-estate developers. For under his guidance, the Roland Park Company was one of the first in the United States to employ competent landscape architects and engineers for site development, to require standards of excellence in design, to impose restrictions on land use and make adequate provisions for maintenance of streets, plantings and parks after completion of the initial development. As architects for the company, Mr. Palmer successfully demonstrated—by designing and supervising the construction of several hundred individual residences—that the insistence of high architectural standards was economically feasible.”

Early in his practice his work focused on two large housing developments. The first was for workers housing for the Bethlehem Steel Corporation in Dundalk, Maryland and the second was for the Dupont Company in Wilmington, Delaware. These were multi-unit, rowhouse type structures of a modest scale, but clearly with distinctive architectural character. But it was his private residential work in the still emerging neighborhoods north of Baltimore City that some of his best work can still be seen and enjoyed. This is especially true when, after 1920, William B. Lamdin joined the firm. In 1925, the firm name was changed by adding new partners to become “Palmer, Willis and Lamdin.” Again in 1929 it changed to simply “Palmer and Lamdin” which had it offices at 513 North Charles Street, in downtown Baltimore.

In the early years of his practice, Palmer set the course for his firm to eventually flourish in Baltimore. One of his first commissions in 1915, seemingly undertaken while he was still with the Roland Park Company, was a house for C. Braxton Dallam at 4001 Greenway. This house was constructed on the site of the original Guilford estate of A.S. Abell. Referred to by local architectural historian, Peter Kurtze, as a “baronial Jacobean mansion” the house is an imposing display of brick arches and steeply pitched roofs, ornate chimneys and other refinements that must have been the hot topic of its day.

Later on, in his work with partner Bill Lamdin, the firm began to develop a definite style, especially in the houses that recall English or French country architecture. Bill Lamdin, who joined the firm in 1923, had served as an Army artillery officer in France in World War I and must have seen and possibly sketched the vernacular architecture of rural France, as so much of its design characteristics are seen in their work.

For an article in the Baltimore News in April 1916, Edward L. Palmer is asked directly “What do you think to be the significance of the houses of Guilford from your point of view?” Palmer responded in his predictably modest manner:

“I can’t give a finished essay off hand on the subject but I can tell you in plain talk what I think it means for us. The main thing about the houses in Guilford, it seems to me, is that they show a serious attempt on the part of the architects to design stuff that is in ‘good grammar.’ That may sound queer, but it is the best simile I can think of. The architecture there is more comparable to correct English than anywhere else . . . Roland Park and Guilford are now really developments that we can be proud of. They possess some splendid houses and many more that are very good. For instance, it isn’t as if Guilford were a place you could find one or two examples of good architecture—the whole place is good.”

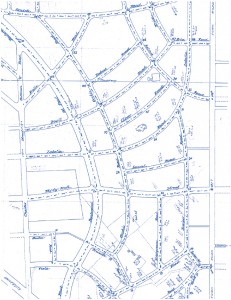

Charles M. Nes (who became a partner in the firm with L. McLane Fisher in 1945, after World War II, when the firm became “Palmer, Lamdin, Fisher, Nes”) said that once Bill Lamdin completed the “Gateway Houses” at Greenway and St. Paul Street in 1925, the firm’s future was secure.These two houses, 3701 St. Paul Street and 3700 Greenway, are not identical or mirror images, but rather complementary in design and present a classic example of the best of Palmer and Lamdin’s work. Bill Lamdin was the designer and his talents are on full display—all the trademark elements are handled with tremendous skill including the steeply pitched roof, the variegated and rusticated slate, decorative masonry, ironwork and ornate chimneys and cornices.These elements will occur again and again in the firm’s work with other touches often added such as stair tower turrets, dovecotes, stone and brick facade interplay.

Other notable and classic examples of their work can be seen throughout Guilford and include 14 St. Martins Road (1929), 3707 Greenway (1929), 4014 Greenway (1914), 4201 and 4205 Underwood Road (1926), 212 Wendover Road (1922), 219 Northway (1925), 4200 Greenway (1914). 101 Wendover Road (1929), 28 Charlcote Place (1929), 210 E. Highfield Road (1926), 7 Stratford Road (1928), The Roland Park Apartments (1925), Second Presbyterian Church (1924). The streets of Roland Park, Guilford and Homeland are rich with the architectural works of this firm. The architectural files of the Roland Park Company retained at the Langsdale Library of the University of Baltimore, document that Edward Palmer and Palmer and Lamdin designed more than 150 Guilford homes, many of them iconic examples of domestic architecture and displaying a mastery of many styles.

This piece was originally published in the Summer 2012 issue of The Guilford News. Walter Schamu FAIA, is president and founder of SMG Architects. He is respected throughout the region for his expertise in historic architecture, and is the founder of Baltimore Architecture Foundation.