We are glad to share this last post in the series from Tom Hobbs, President of the Guilford Association highlighting 100 years of history in Guilford.

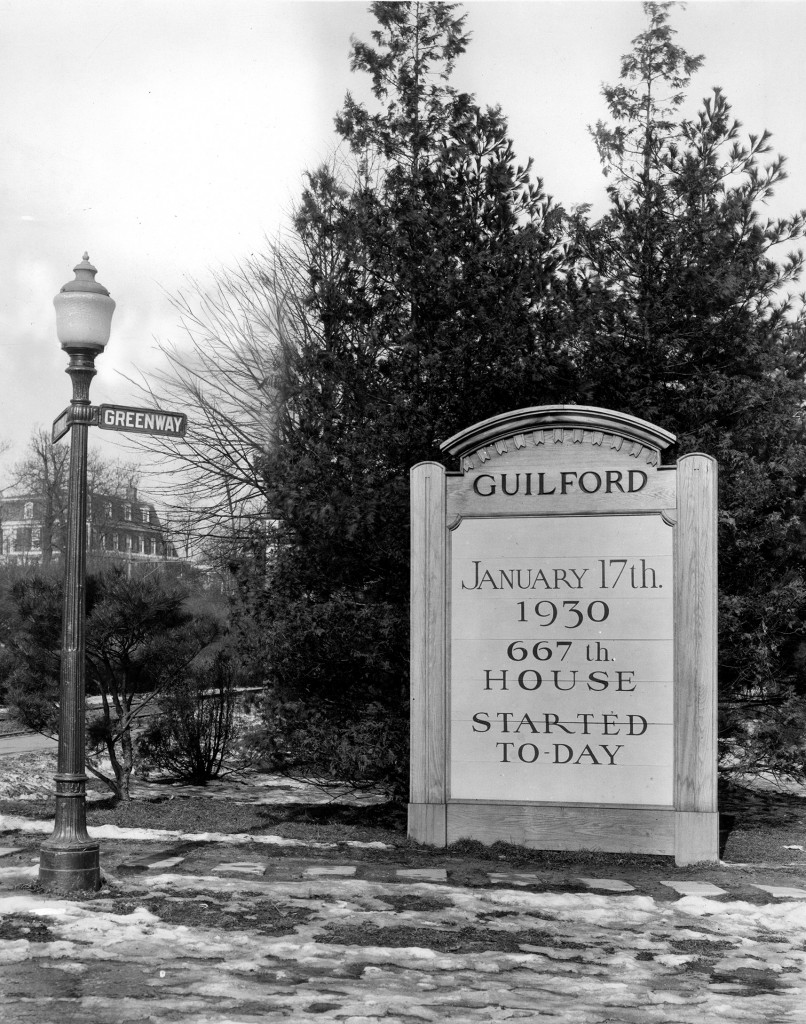

By 1912, construction of the roads and infrastructure was well underway in Guilford and marketing of building sites began in earnest. The sales office was initially located in an original house of the Guilford estate close to Chancery Road. Prospective residents were directed into the community from the southern beginnings of Greenway along a sycamore tree-lined Chancery Road to the sales office and then to the Company-developed Chancery Square.

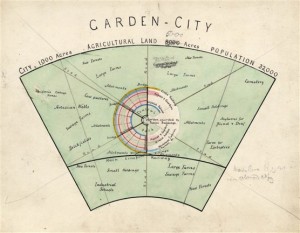

The Roland Park Company built other model homes, many of them designed by Edward Palmer, scattered throughout the development to further the marketing efforts. The success of the garden suburb of Roland Park and the established aesthetic and social value of the community as a desirable area was extended to and enhanced in Guilford. The Roland Park Company marketed the Roland Park-Guilford connection and the desirability of the area as Baltimore’s prestigious location. The prospects for Guilford were made even greater by the move of Johns Hopkins University to the Homewood campus, the decision of the Maryland Episcopal Diocese to purchase the southern tip of Guilford with the intention of building a huge, twin-towered cathedral, and the access to downtown that was direct by extended trolley lines.. These houses were intended to influence the architecture in that particular section but most of the lots were sold to be developed by the buyer and their selected architect. While the Roland Park Company prided itself on planning Guilford for residents with a range of incomes accommodating cottages to mansions, as James Waesche observes in Crowning the Gravelly Hill, “ its intent in Guilford was clear— plenty of room for Baltimore’s biggest spenders.”

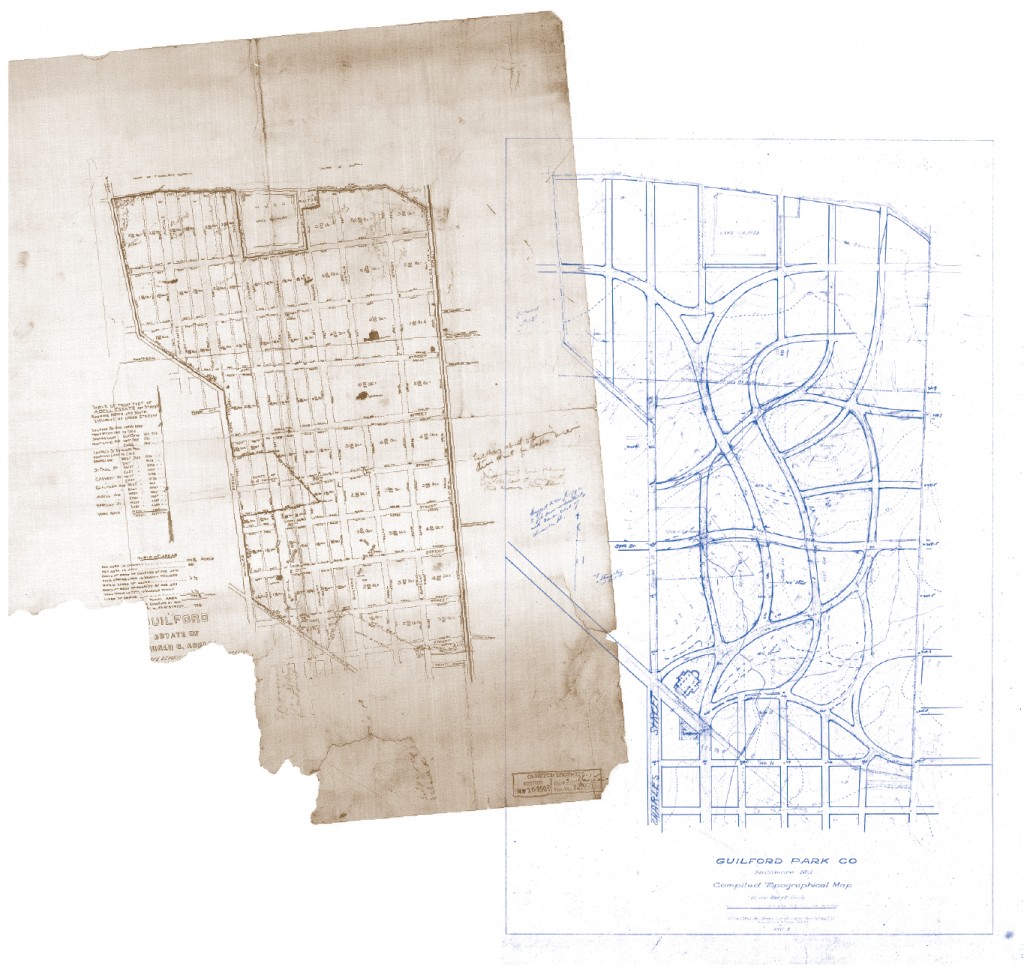

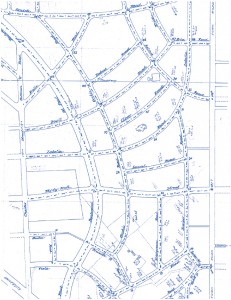

The gently rolling and forested character of the land of the Guilford estate presented an opportunity for a variety of lot sizes. Olmsted’s plan accommodated that intent and further preserved the natural setting in three community parks and private parks spotted in the center of 10 blocks. (Only one of the private inner block parks remains as commonly held by surrounding residents—the block bounded by Northway, Greenway and Stratford Road but in other blocks the areas remain open and undeveloped.)

Along the three boulevard-like spine roads of Charles Street, St. Paul Street and Greenway and in locations adjacent to them sites were divided for the development of large homes, many of which when built have been called “little short of baronial.” J. William Hill, the realtor whose company represented property transfers in the community, commented that “Guilford won almost immediate acceptance as the place to buy, and lawyers, bankers and a number of Hopkins and University physicians set the standard.”

The Roland Park Company’s architectural review committee had to approve all design proposals but allowed development of a number of architectural styles so long as they were skillfully executed, built of fine materials, compatible with the surroundings and “reasonably in accordance with the canons of good taste.” Within fourteen months of the start of sales, 38 houses had been erected and 54 were under construction.

New highly sought after commission opportunities were created for the finest architects to demonstrate their skills. The houses that resulted were to be an expression of the owner’s social status and taste. As Egon Verheyen states in the book Laurence Hall Fowler, Architect, “he was a society architect and the documents assembled in the file on individual commissions attests to his role and the function architecture played in the circles which he frequented.” Styles of Guilford homes were typically based on classic colonial American architecture or European models but the Arts and Crafts influence is also seen particularly in cottage designs. The community thrives on the variety of styles in harmonious relationship.

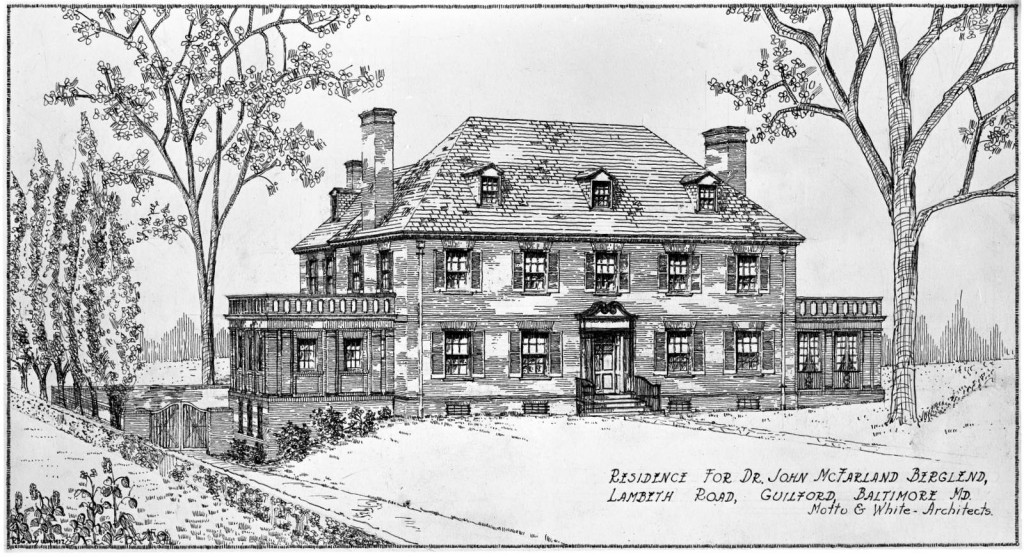

A previous article in this series has discussed the great influence Palmer and Lamdin had on Guilford architecture through the design of many of the community’s most admired homes. Also particularly Palmer was a significant force as the architect for the Roland Park Company and later during the development of Guilford as a key member of the Company’s architectural review committee. The Company retained a list of recommended architects that had demonstrated their residential design skills. The inclusion on this list was highly sought after. Interestingly in the Roland Park files there is a 1913 letter from Mattu & White to Edward Bouton that attests to the value of being on the approved list. They state in the letter:

“. . . as we think our past work compairs (sic) favorably with the work of many of the thirteen Architects on your list, we respectfully request you add our name to your list of Architects which you recommend in connection with the development of Guilford. . . . The discrimination against us is not only harmful to our practice, but most damaging to our reputation. . . .”

Mattu & White ultimately met the screening test and went on to design many of Guilford’s impressive homes.

The core group of architects that molded Guilford, in addition to Palmer and Lamdin, include Laurence Hall Fowler, Howard Sill, John Russell Pope, Mattu & White, Bayard Turnbull and several other designers who had multiple commissions for Guilford homes.

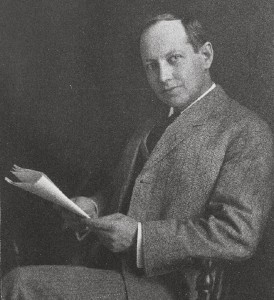

Laurence Hall Fowler was classically trained as an architect. He graduated from Johns Hopkins University and Columbia, traveled through Italy and after a brief apprenticeship in two New York architectural firms he left for Paris in 1904 and was admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He returned to Baltimore and worked briefly at the firm of Wyatt and Nolting. In 1906 he opened his own office making his name designing the homes for those who could afford the luxury of fine taste in Guilford, Blythewood, Gibson Island and the Greenspring Valley. The Garretts were long-time clients and he redesigned the interior of Evergreen House, including the addition of the library. Fowler designed 15 Guilford homes. Examples can be seen 105 and 107 Charlcote Road, 24 and 26 Whitfield Road, and 205 and 207 Wendover Roads. At 33 Warrenton Road there is a particularly fine Tudor revival home that Fowler designed for Harry C. Block. Fowler designed his own home on a Highfield Road site in Tuscany Canterbury— the property currently owned by John Waters.

Howard Sill was a student of colonial American architecture and his designs were focused primarily on modern adaptations of colonial homes. He had carefully studied and measured details and proportions of 18th century Maryland and Virginia buildings and he executed his designs with great care to capture authenticity. In Roland Park he had designed homes on Overhill and Somerset Roads, Merryman Court and Northfield Place and University Parkway. He was well known to Bouton and he like Palmer and Fowler participated on the Architectural Review Committee. He designed at least 13 Guilford homes. Examples can be seen at 204 E. Highfield Road (the Sherwood House), 4405 and 4214 Greenway, 36 Charlcote Place and 3901 St. Paul Street.

In 1914, New York based architect John Russell Pope was selected by James Swan Frick to design Charlcote House on the site in the center of Charlcote Place. Pope studied architecture at Columbia, won the Rome Prize and attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His designs were considered part of the American Renaissance expressed through revival and adaptation of classic styles. He designed homes for the Vanderbilts and many public buildings including the National Archives, the National Gallery, the Jefferson Memorial and the Baltimore Museum of Art where he worked with Howard Sill. While Charlcote House is the only Pope designed house in Guilford, its impact has been great. The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Mattu & White designed 19 Guilford homes – after protesting to Bouton about their exclusion from the Roland Park Company list of approved architects! They proved to be talented in interpreting a number of architectural styles. Their designs can be seen at 3907, 4402 and 4110 Greenway, 3, 16 and 34 Whitfield Road and 40, 42 and 43 Warrenton Road, 229 Lambeth Road and 6 Wendover Road.

Bayard Turnbull is perhaps best known for the design of his artist sister’s home at 223 Chancery Road and for renting a cottage on his Towson property to F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. The Grace Turnbull house is distinguished by its architectural style, an eclectic mix of Spanish Mission and Arts and Crafts elements— a unique structure in Guilford. Turnbull in architectural circles is also noted for designing the Italianate mansion at 4101 Greenway and 4105 Greenway.

This group of architects because of their stature, their skill in interpreting classic designs and their influence within the Roland Park Company are in large part responsible for setting the stage for the architectural quality found in Guilford. A number of other skilled architects contributed to the community whole through their commissions adding significant designs to the harmonious blend of consistently high design standards. The quality of design and construction and the Roland Park Company’s planning, standards and controls together with the provision for continuing oversight have left a legacy that ensures that Guilford will endure as one of the region’s prime places to live.

Thank you again to Tom Hobbs for sharing his writing and research. This piece was originally published in the Spring 2013 issue of The Guilford News.