We were thrilled last month to receive the ONE PARK Award for our work with the Friends of West Baltimore Squares. Eli Pousson (with his daughter) accepted the award from Parks & People Executive Director Jackie Carrera. Learn more about award-winning greening projects and volunteers in West Baltimore from the Friends of West Baltimore Squares.

Tag: Friends of West Baltimore Squares

West Baltimore Squares – Upton gave a neighborhood its name and a unique architectural landmark

Thanks to Baltimore Heritage intern Elise Hoffman for her research on the history of the Upton Mansion. Do you want to share your photos or stories of West Baltimore landmarks? Please get in touch with Eli Pousson at pousson@baltimoreheritage.org or 301-204-337.

High on a hill at 811 West Lanvale Street, behind a chain link fence and past the overgrown yard, is the grand Upton Mansion— an architectural treasure by one of Baltimore’s earliest architects that has witnessed nearly 200 years of change in the Upton neighborhood that shares the building’s name. In the 1830s, Baltimore lawyer David Stewart hired architect Robert Carey Long, Jr., to design his country house. R. Cary (as he liked to call himself) was one of Baltimore’s first professionally trained architects designing the Lloyd Street Synagogue (now part of the Jewish Museum of Maryland), the Patapsco Female Institute in Ellicott City, and the main gate of Greenmount Cemetery among more than 80 buildings across the country. Son of a Baltimore merchant who armed seven schooners and two brigantines as privateers during the Revolutionary War, Stewart became a prominent local lawyer and got involved in politics, serving a brief month as a US Senator in 1849.

The mansion is widely recognized as the last surviving Greek Revival country house in Baltimore. It remains secluded in urban West Baltimore, sitting high above the neighboring buildings and surrounded by brick and stone walls. In the mid-19th century, you would have seen a grand porch with Doric columns and ironwork bearing the Stewart family crest. Inside the building, you could have observed more than a dozen marble and onyx fireplaces, a main entrance hall, a curved oak staircase, and a banquet room that was so large it has since been divided into multiple rooms. David Stewart enjoyed entertaining guests in his mansion and hosted lavish, indulgent parties there so frequently that he developed gout.

After Stewart’s death in 1858, the house was purchased by the Dammann family, who owned the house for so many generations that it became known as “the old Dammann mansion.” The family left in 1901, and the house found itself empty for the first time, but not the last. The mansion’s next owner, musician Robert Young, took a cue from David Stewart and used the spacious and opulent mansion to host “several brilliant social affairs where hundreds of guests moved about in the spacious rooms.” Young would be the last owner to use the building as a home, and his time there was short-lived – he found the mansion too drafty and abandoned after less than 3 years.

The commercial life of the Upton mansion began in 1930 when one of Baltimore’s first radio stations, WCAO, moved into the building. Extensive alterations were made to accommodate WCAO – tall twin radio towers were added to the roof, walls were torn down and rooms partitioned off to create studios and equipment rooms. The next commercial venture in the Upton mansion came in 1947, when WCAO sold it to the Baltimore Institute of Musical Arts. The school was originally opened with the intentions of creating a parallel program to that offered at Peabody, a renowned music school not open to African-American students at the time, though it eventually closed in the mid-1950s after desegregation granted black students equal access to public music schools. In 1957 the Baltimore City School System moved in to the building and used it first as the special education “Upton School for Trainable Children No. 303,” and then the headquarters for Baltimore City Public School’s Home and Hospital Services program. Unfortunately, Upton Mansion has sat empty since BCPS left in 2006.

The Upton mansion has a rich cultural legacy that extends beyond its use as a social hot spot, a radio station, and a school. In the 1960s, the mansion was chosen as the community namesake during an urban renewal project going on in the neighborhood at the time. As a physical landmark of the neighborhood for more than a century, the Upton mansion’s name was intended to serve as “the symbol of a physical and human renewal in West Baltimore.” Despite its presence on the National Register of Historic Places and the Baltimore Landmark List, the city-owned building remains empty and unmaintained in west Baltimore. In 2009, Preservation Maryland included in on a list of the state’s most endangered historic places, and the building is threatened by vandalism and neglect. Today, the mansion awaits a new owner, someone willing to restore the beautiful building to its historic potential.

West Baltimore Squares – Civil rights stories from Parren Mitchell’s home at Lafayette Square

Thanks to Baltimore Heritage intern Elise Hoffman for her research on the history of the Parren Mitchell House. This post is cross-posted from the Friends of West Baltimore Squares blog.

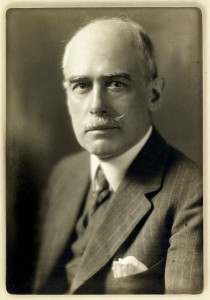

The grand brick rowhouse at 828 North Carrollton Avenue may look like many others in West Baltimore but it has a unique history all its own as the former home of Congressman Parren Mitchell, the first African American congressman from a Southern state since Reconstruction, who lived on Lafayette Square from his retirement in 1988 until shortly before his death in 2007. Even before Parren Mitchell moved to the neighborhood, the house had a long history of civil rights activism as the home of Methodist Bishop Alexander P. Shaw during the 1940s and an office for Bishop Edgar A. Love in the 1950s. Still farther back, when the neighborhood remained segregated white, the rowhouse was home to Colonel J. Thomas Scharf, one of Baltimore’s foremost early historians, who himself opened a window into the early history of West Baltimore neighborhoods.

Built in 1880, this six-bedroom Federal style house was built with a red brick façade and an ornate interior including ten fireplaces with marble mantles, crown molding, and the original wood flooring.Colonel Scharf lived at the house soon after its construction, as early as 1888. His most significant work, The Chronicles of Baltimore; being a complete History of Baltimore town and Baltimore city from the earliest period to the present time, was reviewed as “the most comprehensive and complete book upon the subject ever offered to the public” and remains an essential history of Baltimore. Dr. William B. Burch, a well known community physician, moved his offices into the North Carrollton Avenue address in the early 1900s, joined by the Maryland State Vaccine Agency around 1905 which offered vaccination services to area residents.

Built in 1880, this six-bedroom Federal style house was built with a red brick façade and an ornate interior including ten fireplaces with marble mantles, crown molding, and the original wood flooring.Colonel Scharf lived at the house soon after its construction, as early as 1888. His most significant work, The Chronicles of Baltimore; being a complete History of Baltimore town and Baltimore city from the earliest period to the present time, was reviewed as “the most comprehensive and complete book upon the subject ever offered to the public” and remains an essential history of Baltimore. Dr. William B. Burch, a well known community physician, moved his offices into the North Carrollton Avenue address in the early 1900s, joined by the Maryland State Vaccine Agency around 1905 which offered vaccination services to area residents.

From the 1920s through the 1930s, Lafayette Square was a neighborhood in transition from a largely segregated white neighborhood, anchored by segregated white congregations and institutions like the “Presbyterian Old Folks Home,” also known as the “Presbyterian Home for the Aged of Maryland,” in the Carrollton Avenue home, to become the vibrant African American community that later attracted Parren Mitchell. The Presbyterian Old Folks Home soon relocated to Towson, Maryland and African American congregations moved to occupy all of the churches around the square by the early 1930s. By 1941, Methodist Bishop Alexander P. Shaw moved his offices into the building. Shaw served as the Resident Bishop of the Baltimore Area with a responsibility over 1,300 African American Methodist churches in Maryland, Delaware, DC, North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee. A 1950 Time Magazine profile described Shaw as “consistently [advocating] self-improvement and development” sharing his views in a book, What the Negro Must Do to be Saved, in which he advocated for self-reliance for African-Americans in the face of continuing segregation. Bishop Shaw retired in 1952 and moved to Los Angeles in 1953.

Even after Shaw left, the home on Carrollton Avenue continued to serve as a base for the Methodist Church, becoming the office of Reverend Samuel M. Carter and Bishop Edgar A. Love in 1955. Born in Harrisonburg, Virginia, Edgar Love first came to Baltimore to attend Morgan College for his undergraduate education, later receiving a Doctor of Divinity. Bishop Love was an active advocate against segregation within the Methodist Church, describing it as the “smaller foe” in the battle against segregation and racism. In one of his first acts as a Bishop within the church, Love arranged a meeting with then President elect Dwight Eisenhower leading to the creation of a commission to study segregation practices against minority groups in the United States. Through the 1950s, Love worked against segregation within the church, pushing for Methodist churches, colleges, and hospitals open their doors to all people regardless of race.His achievements and work as a civil rights advocated were well recognized with Love participating as an honored guest at the 1963 March on Washington and later serving as a member of the Maryland Interracial Commission.

With such a rich legacy of civil rights activism in Lafayette Square it came as no surprise when in 1988 Congressman Parren Mitchell moved from his home on Madison Avenue to the rowhouse at Carrollton and Lafayette. Elected in 1971, Parren Mitchell was the first African American congressman from the state of Maryland, the first from a southern state since Reconstruction, and soon became a founding members and leading voice within the Congressional Black Caucus. Born in Baltimore in 1922, Mitchell graduated from West Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School in 1940. After service in WWII, Mitchell graduated from Morgan State University with honors in 1950 but segregation at the University of Maryland College Park campus barred him from attending the University of Maryland Graduate School. On the advice of his brother Clarence Mitchell Jr., who worked as the chief lobbyist for the NAACP for nearly 30 years, Parren Mitchell and his lawyer Thurgood Marshall successfully sued the University of Maryland, gaining his admission to the graduate school and becoming the first African-American to graduate. As a congressman from 1971 through 1988, Mitchell established the Minority Business Enterprise Legal Defense and Education Fund and ensured millions of dollars of support for minority business owners. Since his death in 2007, the home has remained well maintained but empty, waiting for the next resident interested in taking on the home’s tremendous legacy.

With such a rich legacy of civil rights activism in Lafayette Square it came as no surprise when in 1988 Congressman Parren Mitchell moved from his home on Madison Avenue to the rowhouse at Carrollton and Lafayette. Elected in 1971, Parren Mitchell was the first African American congressman from the state of Maryland, the first from a southern state since Reconstruction, and soon became a founding members and leading voice within the Congressional Black Caucus. Born in Baltimore in 1922, Mitchell graduated from West Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School in 1940. After service in WWII, Mitchell graduated from Morgan State University with honors in 1950 but segregation at the University of Maryland College Park campus barred him from attending the University of Maryland Graduate School. On the advice of his brother Clarence Mitchell Jr., who worked as the chief lobbyist for the NAACP for nearly 30 years, Parren Mitchell and his lawyer Thurgood Marshall successfully sued the University of Maryland, gaining his admission to the graduate school and becoming the first African-American to graduate. As a congressman from 1971 through 1988, Mitchell established the Minority Business Enterprise Legal Defense and Education Fund and ensured millions of dollars of support for minority business owners. Since his death in 2007, the home has remained well maintained but empty, waiting for the next resident interested in taking on the home’s tremendous legacy.

West Baltimore Squares – Remembering the Celestial Ceiling of the Harlem Theatre

Thanks to Baltimore Heritage intern Elise Hoffman for researching and writing this post on the history of the Harlem Theatre. This post is cross-posted from the Friends of West Baltimore Squares blog.

The Harlem Theatre, now known as the Harlem Park Community Baptist Church, is a local landmark on the western edge of Harlem Park– one of the city’s most extravagant African American movie theaters with a unique “celestial ceiling” featuring “twinkling electrical stars and projected clouds.” Built in 1902 as the home for the Harlem Park Methodist Episcopal Church, after they out grew their previous building, the structure still retains its ornamental Romanesque style with arched doors and windows made of rough blocks of Port Deposit granite.

Harlem Park Methodist Episcopal Church did not remain in the area long however. After the building opened in 1903, two destructive fires — in December of 1908 followed by an even more severe fire in 1924 — led the congregation to sell the building and move out to a new church at Harlem and Warwick Avenues at the western edge of the developing city. At the same time the neighborhood began to transition from a largely segregated white to a predominantly black community, a change that almost certainly influenced the white congregation. In 1928, the congregation sold the church to Emanuel M. Davidove and Harry H. Goldberg, owners of the new Fidelity Amusement Corporation, established to build “a 1,500 seat motion picture theatre for Negroes…to be known as Harlem Theatre.”

The company hired architect Theodore Wells Pietsch, a notable Baltimore architect who also designed Eastern High School and the Broadway Pier. Pietsch took the property’s history into consideration when designing the new building: the theatre was made fireproof through the use of steel and concrete, and a fire extinguishing system was also included in the building’s design. Pietsh’s new design had an elaborate Spanish Mission theme described at the time as one of most elaborate designs on the East Coast and promoted as “the best illuminated building in Baltimore.” The bright façade included a 65-foot marquee with 900 50-watt light bulbs illuminating sidewalk underneath, “tremendous electric signs” around the marquee, and a forty-foot tall sign that could be seen from two miles away.

The company hired architect Theodore Wells Pietsch, a notable Baltimore architect who also designed Eastern High School and the Broadway Pier. Pietsch took the property’s history into consideration when designing the new building: the theatre was made fireproof through the use of steel and concrete, and a fire extinguishing system was also included in the building’s design. Pietsh’s new design had an elaborate Spanish Mission theme described at the time as one of most elaborate designs on the East Coast and promoted as “the best illuminated building in Baltimore.” The bright façade included a 65-foot marquee with 900 50-watt light bulbs illuminating sidewalk underneath, “tremendous electric signs” around the marquee, and a forty-foot tall sign that could be seen from two miles away.

In October 1932, the owners organized a celebration to open the theater “in a blaze of glory” drawing jubilant crowds of 5,000 to 8,000 people. The jubilant scene was described by a journalist:

“The blazing marquee studded with a thousand lights made the entire square take a semblance of Broadway glamour. The marquees illuminated the entire Harlem Square which was crowded with those who lined the sidewalk unable to gain admittance.”

Over the next forty years, countless numbers of Baltimore residents enjoyed the theatre’s “cavernous three-story high ceiling, a balcony, carpeted floors and thick cushioned seats” and “celestial ceiling with twinkling electrical stars and projected clouds that floated over movie-goers’ heads.” The Harlem Theatre also hosted events supporting the broader community, such as a free “Movie Jamboree” in 1968 for the children of Baltimore workers donated by the theatre’s then-manager Edward Grot, and midnight shows to raise money for the local YMCA. Unfortunately for the Harlem, as movie theatres that previously discriminated against black customers began to desegregate in the mid 20th century, their business declined. By the mid-1970s, the Harlem Theatre had closed.

The building took on a new life in 1975 when Reverend Raymond Kelley, Jr. purchased the old theater and turned it into the Harlem Park Community Baptist Church dedicated on July 6, 1975. The building has been refurbished– the congregation traded in the old theater seats for pews and removed the large marquee–but much of the original historic character remains intact. Of course, the story of the Harlem Theatre also remains in the memories of thousands of Baltimore residents and we hope you can share your stories with us in the comments.

Do you want to share your photos or stories of West Baltimore landmarks? Please get in touch with Eli Pousson at pousson@baltimoreheritage.org or 301-204-337.

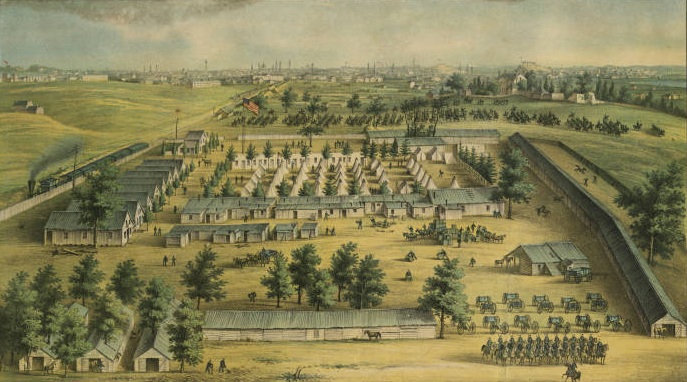

Civil War 150: West Baltimore’s Civil War History by Bike — Rescheduled

Many people know that President Street Station has its roots in the Civil War, but few know that Civil War history can be found throughout the city, including many sites in West Baltimore. In fact, West Baltimore neighborhoods served a central role in the conflict– housing Union troops on their south to fight, caring for injured soldiers, and witnessing the many ways in which the conflict on the battlefield came home to the city 150 years ago. As the home to the B&O Railroad, West Baltimore supported the movement of troops by train (a key advantage for the Union) and protected the city from invasion by Confederate troops through a ring of camps, hospitals and fortifications in Carroll Park, on Baltimore Street, in Lafayette Square and more.

West Baltimore’s Civil War History by Bike

Update: Due to today’s rainy and snowy weather, we have rescheduled our tour to Saturday, November 5, 10:00 am. Please contact Eli Pousson at pousson@baltimoreheritage.org or 301-204-3337 with any questions or concerns.

October 29, 2011, 10:00 am to 11:30 am

$10 for members & non-members, RSVP today!

This 90-minute bicycle tour starts and ends at the Mt. Clare Museum House rolling past rowhouses, parks, stables, and shops, scores of historic places grand and modest, where people lived and worked during the Civil War and its aftermath. We’ll learn about Confederate spies at Waverly Terrace in Franklin Square, take a look at the historic artifacts we recently dug up from the site of Lafayette Barracks, and trace the lives of immigrant workers who built the trains, bridges, and more that the Union military depended on at the Irish Shrine at Lemmon Street and the B&O Railroad Roundhouse. Please join us as we pedal through the history of the Civil War in West Baltimore and commemorate this nation-shaping event of 150 years ago.

Thanks to the support of Free Fall Baltimore at the end of the tour participants are welcome to take a free tour of the Mt. Clare Museum House. Mount Clare is a 1760 colonial Georgian home built by Charles Carroll and Maryland’s oldest house museum.

Connect with the Friends of West Baltimore Squares to learn more about heritage and community greening programs in West Baltimore neighborhoods!