Thanks to Baltimore Heritage intern Elise Hoffman for her research on the history of the Parren Mitchell House. This post is cross-posted from the Friends of West Baltimore Squares blog.

The grand brick rowhouse at 828 North Carrollton Avenue may look like many others in West Baltimore but it has a unique history all its own as the former home of Congressman Parren Mitchell, the first African American congressman from a Southern state since Reconstruction, who lived on Lafayette Square from his retirement in 1988 until shortly before his death in 2007. Even before Parren Mitchell moved to the neighborhood, the house had a long history of civil rights activism as the home of Methodist Bishop Alexander P. Shaw during the 1940s and an office for Bishop Edgar A. Love in the 1950s. Still farther back, when the neighborhood remained segregated white, the rowhouse was home to Colonel J. Thomas Scharf, one of Baltimore’s foremost early historians, who himself opened a window into the early history of West Baltimore neighborhoods.

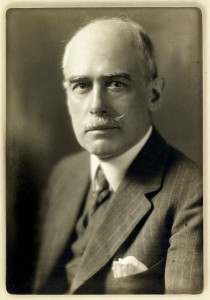

Built in 1880, this six-bedroom Federal style house was built with a red brick façade and an ornate interior including ten fireplaces with marble mantles, crown molding, and the original wood flooring.Colonel Scharf lived at the house soon after its construction, as early as 1888. His most significant work, The Chronicles of Baltimore; being a complete History of Baltimore town and Baltimore city from the earliest period to the present time, was reviewed as “the most comprehensive and complete book upon the subject ever offered to the public” and remains an essential history of Baltimore. Dr. William B. Burch, a well known community physician, moved his offices into the North Carrollton Avenue address in the early 1900s, joined by the Maryland State Vaccine Agency around 1905 which offered vaccination services to area residents.

Built in 1880, this six-bedroom Federal style house was built with a red brick façade and an ornate interior including ten fireplaces with marble mantles, crown molding, and the original wood flooring.Colonel Scharf lived at the house soon after its construction, as early as 1888. His most significant work, The Chronicles of Baltimore; being a complete History of Baltimore town and Baltimore city from the earliest period to the present time, was reviewed as “the most comprehensive and complete book upon the subject ever offered to the public” and remains an essential history of Baltimore. Dr. William B. Burch, a well known community physician, moved his offices into the North Carrollton Avenue address in the early 1900s, joined by the Maryland State Vaccine Agency around 1905 which offered vaccination services to area residents.

From the 1920s through the 1930s, Lafayette Square was a neighborhood in transition from a largely segregated white neighborhood, anchored by segregated white congregations and institutions like the “Presbyterian Old Folks Home,” also known as the “Presbyterian Home for the Aged of Maryland,” in the Carrollton Avenue home, to become the vibrant African American community that later attracted Parren Mitchell. The Presbyterian Old Folks Home soon relocated to Towson, Maryland and African American congregations moved to occupy all of the churches around the square by the early 1930s. By 1941, Methodist Bishop Alexander P. Shaw moved his offices into the building. Shaw served as the Resident Bishop of the Baltimore Area with a responsibility over 1,300 African American Methodist churches in Maryland, Delaware, DC, North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee. A 1950 Time Magazine profile described Shaw as “consistently [advocating] self-improvement and development” sharing his views in a book, What the Negro Must Do to be Saved, in which he advocated for self-reliance for African-Americans in the face of continuing segregation. Bishop Shaw retired in 1952 and moved to Los Angeles in 1953.

Even after Shaw left, the home on Carrollton Avenue continued to serve as a base for the Methodist Church, becoming the office of Reverend Samuel M. Carter and Bishop Edgar A. Love in 1955. Born in Harrisonburg, Virginia, Edgar Love first came to Baltimore to attend Morgan College for his undergraduate education, later receiving a Doctor of Divinity. Bishop Love was an active advocate against segregation within the Methodist Church, describing it as the “smaller foe” in the battle against segregation and racism. In one of his first acts as a Bishop within the church, Love arranged a meeting with then President elect Dwight Eisenhower leading to the creation of a commission to study segregation practices against minority groups in the United States. Through the 1950s, Love worked against segregation within the church, pushing for Methodist churches, colleges, and hospitals open their doors to all people regardless of race.His achievements and work as a civil rights advocated were well recognized with Love participating as an honored guest at the 1963 March on Washington and later serving as a member of the Maryland Interracial Commission.

With such a rich legacy of civil rights activism in Lafayette Square it came as no surprise when in 1988 Congressman Parren Mitchell moved from his home on Madison Avenue to the rowhouse at Carrollton and Lafayette. Elected in 1971, Parren Mitchell was the first African American congressman from the state of Maryland, the first from a southern state since Reconstruction, and soon became a founding members and leading voice within the Congressional Black Caucus. Born in Baltimore in 1922, Mitchell graduated from West Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School in 1940. After service in WWII, Mitchell graduated from Morgan State University with honors in 1950 but segregation at the University of Maryland College Park campus barred him from attending the University of Maryland Graduate School. On the advice of his brother Clarence Mitchell Jr., who worked as the chief lobbyist for the NAACP for nearly 30 years, Parren Mitchell and his lawyer Thurgood Marshall successfully sued the University of Maryland, gaining his admission to the graduate school and becoming the first African-American to graduate. As a congressman from 1971 through 1988, Mitchell established the Minority Business Enterprise Legal Defense and Education Fund and ensured millions of dollars of support for minority business owners. Since his death in 2007, the home has remained well maintained but empty, waiting for the next resident interested in taking on the home’s tremendous legacy.

With such a rich legacy of civil rights activism in Lafayette Square it came as no surprise when in 1988 Congressman Parren Mitchell moved from his home on Madison Avenue to the rowhouse at Carrollton and Lafayette. Elected in 1971, Parren Mitchell was the first African American congressman from the state of Maryland, the first from a southern state since Reconstruction, and soon became a founding members and leading voice within the Congressional Black Caucus. Born in Baltimore in 1922, Mitchell graduated from West Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School in 1940. After service in WWII, Mitchell graduated from Morgan State University with honors in 1950 but segregation at the University of Maryland College Park campus barred him from attending the University of Maryland Graduate School. On the advice of his brother Clarence Mitchell Jr., who worked as the chief lobbyist for the NAACP for nearly 30 years, Parren Mitchell and his lawyer Thurgood Marshall successfully sued the University of Maryland, gaining his admission to the graduate school and becoming the first African-American to graduate. As a congressman from 1971 through 1988, Mitchell established the Minority Business Enterprise Legal Defense and Education Fund and ensured millions of dollars of support for minority business owners. Since his death in 2007, the home has remained well maintained but empty, waiting for the next resident interested in taking on the home’s tremendous legacy.

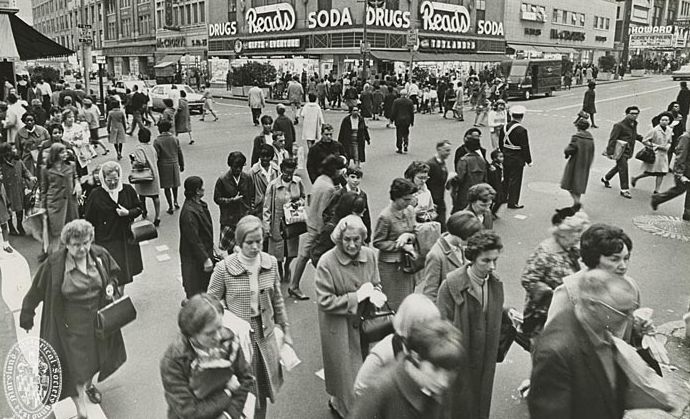

For over two hundred years this neighborhood has been a center of activity to entrepreneurs and merchants of all kinds, suffragists and civil rights protestors, and much more. With all of these diverse stories to tell, we’re bringing back last winter’s Why the West Side Matters series here on our website and offering a new set of lunch time walking tours on the second Wednesday of each month from January through April 2012.

For over two hundred years this neighborhood has been a center of activity to entrepreneurs and merchants of all kinds, suffragists and civil rights protestors, and much more. With all of these diverse stories to tell, we’re bringing back last winter’s Why the West Side Matters series here on our website and offering a new set of lunch time walking tours on the second Wednesday of each month from January through April 2012.