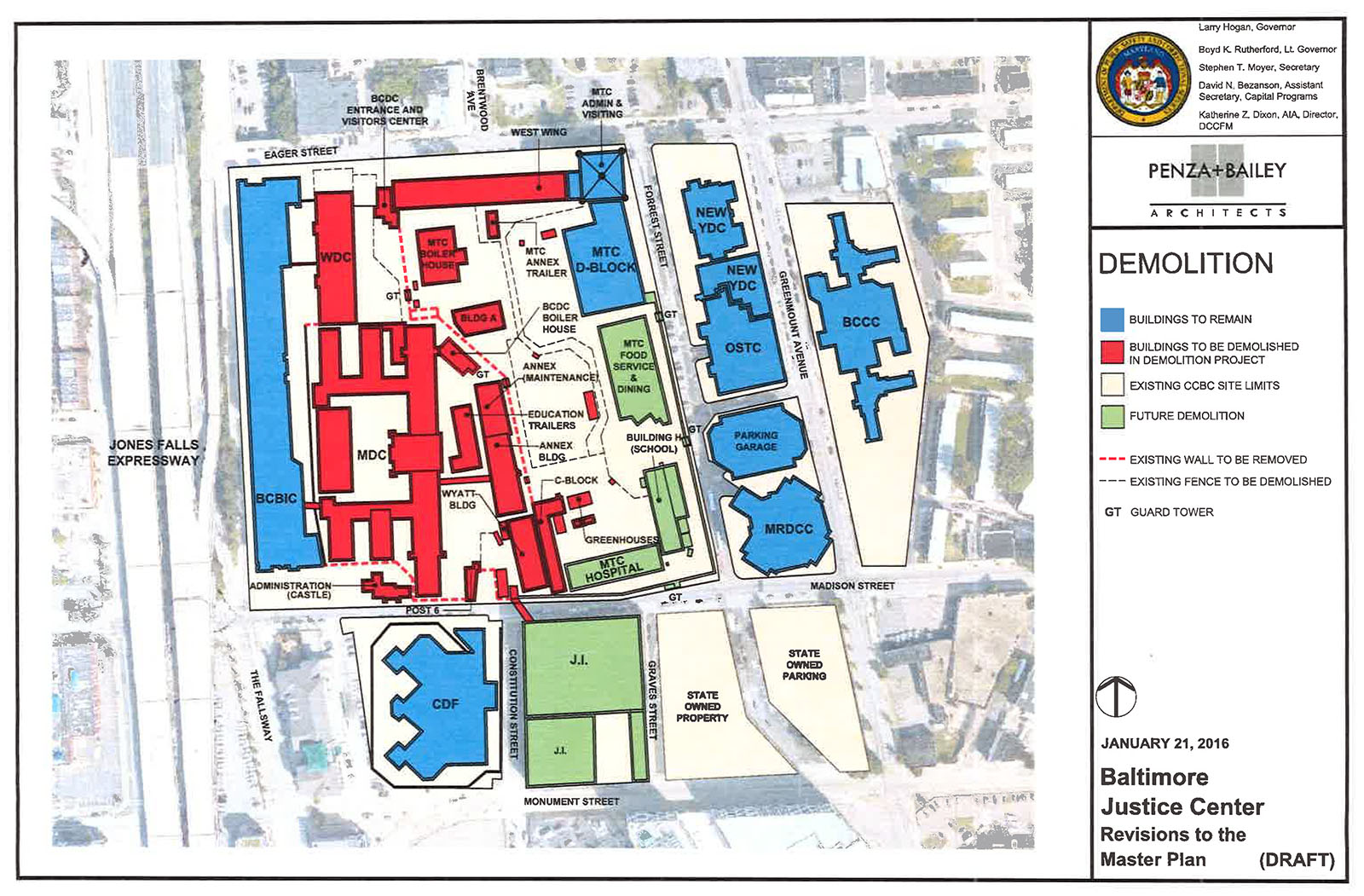

Last month, the Maryland Department of Corrections (MDC) released their preliminary plan for the demolition of the Baltimore City Detention Center. Governor Larry Hogan announced the immediate closure Baltimore jail last July following years of concerns and controversy over conditions for inmates and corrections officers. MDC is now seeking to tear down several significant historic buildings including the 157-year-old Warden’s House and the west wing of the iconic Maryland Penitentiary whose turrets have stood out in the Baltimore skyline since the early 1890s. If the Maryland General Assembly funds the project, estimated to cost $482 million, MDC hopes to start design work in July 2016 and start demolition in March 2017.

We recognize the urgent need to fix the long-standing issues at the facility but we believe both the Warden’s House and Maryland Penitentiary building can be reused by the Maryland Department of Corrections or partner organizations. Baltimore Heritage is opposed to the current plan to tear down these significant buildings and we are committed to seeking alternatives to demolition.

The Baltimore Jail is a complex of buildings occupying the block between Madison and Eager Streets just east of the Jones Falls Expressway. In addition to the Warden’s House on East Madison Street and the west wing of the Maryland Penitentiary on East Eager Street, the demolition proposal also includes tearing down the Men and Women’s Detention Center Buildings completed in 1967, and a historic laundry, school, and power plant all dating back to the 19th century.

Warden’s House (1855-1859)

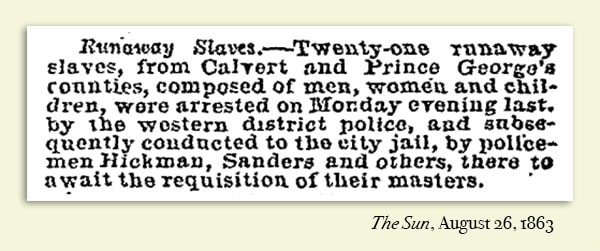

Known to many simply as the “Castle”, the Warden’s House won recognition for its unique Gothic design when it was designated a Baltimore City landmark in 1986. Despite the designation, state agencies like the Maryland Department of Corrections are not bound by local protections for landmark structures. Noted as the work of local architects James and Thomas Dixon, the Warden’s House is perhaps even more important as a reminder of Baltimore’s antebellum history of slavery.

From 1859 to 1864, the Baltimore Jail was used to hold hundreds of “runaways” along with Marylanders, both white and black, who assisted enslaved people as they fled to freedom. At the time, a number of private slave jails operated around the Baltimore Harbor but none of those buildings have survived through the present. Today, the Warden’s House is a rare physical reminder of how the slave trade and resistance to slavery dominated Baltimore’s civic life.

Maryland Penitentiary (1897)

The Maryland Penitentiary on Eager Street is remarkable in other ways. Completed in 1897, as part of a prison reform building boom, the building was designed by architect Jackson C. Gott. Gott served as one of eight founding members of Baltimore’s chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1870. He designed the Masonic Temple and Eastern Pumping Station in Baltimore, as well as Western Maryland College (now McDaniel College) in Westminster. For the Penitentiary, Gott’s Romanesque Revival design and his choice of heavy Port Deposit granite created a landmark whose appearance truly reflects its somber purpose.

MDC cited structural concerns in their proposal to demolish the west wing of this structure but, based on our recent site tour, the issues only affect the interior metal structure that makes up the cells. State officials acknowledged that they have not seen any structural issues with the exterior stone walls.

What happens next?

State law requires the Maryland Department of Corrections to participate in a preservation review process administered by the Maryland Historical Trust. Baltimore Heritage, along with Preservation Maryland, is working through the review process to seek a revised proposal that preserves these important landmarks. We want to hear your comments, questions and concerns. Please get in touch or sign up below for updates as we continue work on this issue throughout the year.

[gravityform id=”25″ title=”true” description=”false”]

All you have to do is look at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia to see how successful a redevelopment of a place like this can be.

Why can’t they build on the State-owned block bounded by Madison, Graves, Monument and Greenmount, which is completely vacant and essentially across the street? They could still demolish the southern and eastern parts of the existing compound, essentially scooting the entire footprint to the southeast. That would allow them to save the West Wing, which would make for an interesting property for St. Frances and other like minded youth-positive organizations to move into.

It saddens me that the initial plan for old buildings is demolition. Repurposing these structures allows us to find new innovative uses for them while maintaining our architectural history.

Ignorance perpetuates itself among those who have nothing from the past from which to learn from.

I can’t believe they plan to spend around $482,000 just to demolish these buildings when we have a problem with homelessness and job training in Baltimore and in Maryland. Why not redevelop the building to house the homeless, provide food for them and working poor (a “soup kitchen” for lack of a better term) and a training center. The homeless can learn job skills in food service while working in the kitchen at the facility as well as computer skills, hospitality training, etc. Remove the bars such as shown in the top photo and replace the cell doors with regular doors, remove the lead paint and/or asbestos.

Its $482 million, not thousand.

I am all for that.

Craig is right. Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia has been successfully repurposed. The historic buildings should be preserved.

I’d like to see some bigger thinking for the real estate between the Johns Hopkins Medical Complex and Downtown Baltimore. Creating synergy between the two would be good for both Johns Hopkins and downtown. Imagine a central city that had residents and commerce completely integrating the two, instead of being utterly isolated from each other.

I wonder how many of the commenters would want the home “repurposed” where their loved one was raped or murdered? Or let’s repurpose the basement of a structure where you were held hostage and brutalized. These discussions are always conducted by people who have no first hand experience with the thing that represents pain and trauma for many. Those who are traumatized are rarely the ones who want to keep reminders of the source of their trauma. That usually comes from those who are high minded and idealistic about “remembering”.

True, but at the same time that violence & brutality is part of the city’s history. I wouldn’t advocate tearing down slave quarters or concentration camps either (different but same principle). Those are structures that bring traumatic histories to the public in a tangible way right in the community. I would argue it’s worth preserving to help future generations understand that history (and yes, the violence and pain that was very much a part of it) even if it represents moments we are not proud of. I don’t think it’s idealistic, who wants to remember the hard stuff? But necessary to understanding who we are as a city and where we come from.

So then why don’t we tear down every house in the city, because i’m sure terrible things happened there too. The money could be put to better use.

Pretty building. Hope they save it.

I worked in corrections for 21 years and retired as a

Lieutenant. I worked in this building for three years in an administrative position. It would be a historical travesty to demolish a timepiece such as this, that takes us back to one of the most important

events of humankind. I always appreciated the opportunity to actually work on property that my people were apart of the deep rich history.

This place needs to be preserved in the same way the Bastille was.

The fight for historical preservation cannot just be rhetorical. We must stop the bulldozers.

#MobTown