Thanks to Baltimore Heritage intern Elise Hoffman for her research on the history of the Upton Mansion. Do you want to share your photos or stories of West Baltimore landmarks? Please get in touch with Eli Pousson at pousson@baltimoreheritage.org or 301-204-337.

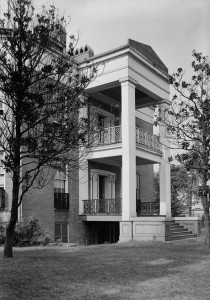

High on a hill at 811 West Lanvale Street, behind a chain link fence and past the overgrown yard, is the grand Upton Mansion— an architectural treasure by one of Baltimore’s earliest architects that has witnessed nearly 200 years of change in the Upton neighborhood that shares the building’s name. In the 1830s, Baltimore lawyer David Stewart hired architect Robert Carey Long, Jr., to design his country house. R. Cary (as he liked to call himself) was one of Baltimore’s first professionally trained architects designing the Lloyd Street Synagogue (now part of the Jewish Museum of Maryland), the Patapsco Female Institute in Ellicott City, and the main gate of Greenmount Cemetery among more than 80 buildings across the country. Son of a Baltimore merchant who armed seven schooners and two brigantines as privateers during the Revolutionary War, Stewart became a prominent local lawyer and got involved in politics, serving a brief month as a US Senator in 1849.

The mansion is widely recognized as the last surviving Greek Revival country house in Baltimore. It remains secluded in urban West Baltimore, sitting high above the neighboring buildings and surrounded by brick and stone walls. In the mid-19th century, you would have seen a grand porch with Doric columns and ironwork bearing the Stewart family crest. Inside the building, you could have observed more than a dozen marble and onyx fireplaces, a main entrance hall, a curved oak staircase, and a banquet room that was so large it has since been divided into multiple rooms. David Stewart enjoyed entertaining guests in his mansion and hosted lavish, indulgent parties there so frequently that he developed gout.

After Stewart’s death in 1858, the house was purchased by the Dammann family, who owned the house for so many generations that it became known as “the old Dammann mansion.” The family left in 1901, and the house found itself empty for the first time, but not the last. The mansion’s next owner, musician Robert Young, took a cue from David Stewart and used the spacious and opulent mansion to host “several brilliant social affairs where hundreds of guests moved about in the spacious rooms.” Young would be the last owner to use the building as a home, and his time there was short-lived – he found the mansion too drafty and abandoned after less than 3 years.

The commercial life of the Upton mansion began in 1930 when one of Baltimore’s first radio stations, WCAO, moved into the building. Extensive alterations were made to accommodate WCAO – tall twin radio towers were added to the roof, walls were torn down and rooms partitioned off to create studios and equipment rooms. The next commercial venture in the Upton mansion came in 1947, when WCAO sold it to the Baltimore Institute of Musical Arts. The school was originally opened with the intentions of creating a parallel program to that offered at Peabody, a renowned music school not open to African-American students at the time, though it eventually closed in the mid-1950s after desegregation granted black students equal access to public music schools. In 1957 the Baltimore City School System moved in to the building and used it first as the special education “Upton School for Trainable Children No. 303,” and then the headquarters for Baltimore City Public School’s Home and Hospital Services program. Unfortunately, Upton Mansion has sat empty since BCPS left in 2006.

The Upton mansion has a rich cultural legacy that extends beyond its use as a social hot spot, a radio station, and a school. In the 1960s, the mansion was chosen as the community namesake during an urban renewal project going on in the neighborhood at the time. As a physical landmark of the neighborhood for more than a century, the Upton mansion’s name was intended to serve as “the symbol of a physical and human renewal in West Baltimore.” Despite its presence on the National Register of Historic Places and the Baltimore Landmark List, the city-owned building remains empty and unmaintained in west Baltimore. In 2009, Preservation Maryland included in on a list of the state’s most endangered historic places, and the building is threatened by vandalism and neglect. Today, the mansion awaits a new owner, someone willing to restore the beautiful building to its historic potential.