Thanks to Kathleen Kotarba, Executive Director of Baltimore’s Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation, for sharing a guest post on the Defender’s Day Weekend rededication of two War of 1812 monuments in Federal Hill Park and the story behind their conservation.

Join Governor Martin J. O’Malley, former Senator Paul Sarbanes, Congressman John Sarbanes, Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, Major General Jeffrey S. Buchanan, Commanding General of the Military District of Washington, and South Baltimore neighbors celebration and rededication of the Sam Smith Monument and Armistead Monument at Federal Hill Park. The US Army 3rd Infantry’s “Old Guard” Fife and Drum Corps, the Maryland National Guard Honor Guard, and the Maryland Defense Force Buglers will perform, accompanied by a Military Retreat and lowering of Federal Hill’s distinctive 15-Star Flag.

Celebrate and Rededicate War of 1812 Monuments on Federal Hill

Saturday, September 14, 2013, 5:00pm

Federal Hill Park, 300 Warren Avenue, Baltimore, MD 21230

The ceremony is co-hosted by South Harbor Renaissance, Inc. and the Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks, with the cooperation of the Maryland Military Monuments Commission and the Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation.

Major General Samuel Smith Monument, 1917

The Samuel Smith Monument was one of several sculptural monuments commissioned in recognition of Baltimore’s Centennial of the War of 1812. General Smith was commander of the Maryland forces that repulsed and defeated the British in the Battle of Baltimore at North Point and at Fort McHenry on September 12-14, 1814. Previously, Smith had been a hero of the Revolutionary War. After his exemplary military career, he continued his public service by serving forty years in Congress including becoming President of the U.S. Senate, serving as Secretary of the U.S Navy, and at the age of 80 serving as the Mayor of Baltimore.

Prominent Baltimore sculptor Hans Schuler received three commissions during the Centennial of the War of 1812, including the monument to General Smith. Schuler’s sculpture artfully presents the strength of the General, standing in his military uniform from the War of 1812. This 1917 monument has been relocated twice and was originally located in the southeastern edge of Wyman Park. In 1953, the monument moved to a park named for Samuel Smith at the corner of Pratt and Light Streets. In 1970, General Smith’s monument was moved to its current Federal Hill Park location, overlooking the grand view of Baltimore’s harbor and skyline.

In January of 2012, the Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation (CHAP) determined that structural conditions within the monument’s base required the City’s immediate attention. In Summer of 2013, CHAP engaged Conservator of Fine Art, Steven Tatti, to conduct a comprehensive conservation of the monument, including the necessary reconstruction of the base.

The bronze statue of Samuel Smith was removed and secured to allow for the dismantling of the granite base. The statue of Smith was carefully cleaned and the bronze received a heated wax conservation treatment. The granite sections of the monument base were completely dismantled and placed adjacent to the monument. The existing structural pad was then cleaned and prepped for the reconstruction of the base. The one broken section of granite was repaired prior to reinstallation. The granite sections were gently cleaned to avoid potential damage. The monument base was then reconstructed and repointed, course by course, to restore its stability. It was very important to get each course level and plumb to insure that the bronze statue could be reinstalled securely.

Once the granite base was reconstructed, the bronze statue of Smith was returned the top of the monument. The projected was funded by the City of Baltimore, through CHAP’s Monument Restoration Program in the Department of Planning, with additional contributions of the Maryland Military Monument’s Commission.

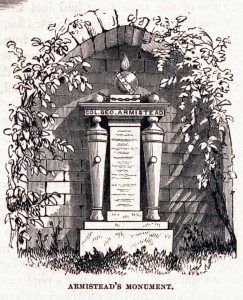

Colonel George Armistead Monument, 1882

The Mayor and City Council of Baltimore erected the Colonel George Armistead Monument on Eutaw Place on September 12, 1882. Armistead was commander of Fort McHenry during the British attack of September 13-13, 1814. The architectural firm of G. Metzger designed this monument that features the outline of Armistead’s career in the inscription on the shaft. The marble block of fourteen feet rests on a base a foot and a half high. This monument was commissioned as a “substitute” for an earlier ca. 1828 tablet of commemoration that became defaced and destroyed by time.

As with the Samuel Smith Monument, the Armistead Monument was moved from its original location. Designed for its initial installation on Eutaw Place, the monument was subsequently moved to Federal Hill after residents protested that its height did not harmonize with the loftiness of their homes. Today, the strong architectural presence of the Armistead Monument anchors the Federal Hill overlook in close proximity to the Samuel Smith Monument.

In summer of 2013, CHAP engaged Conservator of Fine Art, Steven Tatti, again to conserve the Armisted Monument. The original lower tier of the stacked stone foundation was cleaned and shimmed as needed. The stone foundation, as well as the joint between the foundation and the monument base, was then repointed with an appropriate sand cement mortar mix. The monument itself was gently washed, carefully avoiding damaging the fragile stone. The ornamental fence was then cleaned, prepped and repainted with alkyd black semi-gloss paint. The projected was funded by the City of Baltimore, through CHAP’s Monument Restoration Program in the Department of Planning, with the additional contributions of the Maryland Military Monument’s Commission and the City-wide Adopt A Monument Fund.

This post is based on the September 2013 Monument Project Conservation Report available from CHAP.