Enjoy a unique behind the scenes look at the former Centre Theater in today’s photo-filled post on the layered history of 10 East North Avenue. Brennen Jensen is a freelance writer who tromped through many abandoned-but-slated-for-

The painted message high on a cement wall reads “Roll Slow Blow Horn”—not that you can see (or photograph) it all at once through the tattered remains of an erstwhile drop ceiling. I’m standing inside the Centre Theatre building at 10 E. North Ave. Its deco-moderne facade of white travertine and contrasting black soapstone dates to 1939, but as this signage from the past shows, the structure—at least some of it—had an earlier life.

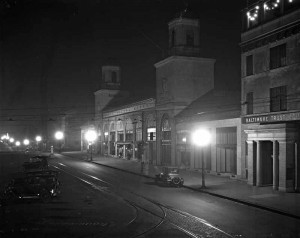

Before it was a glamorous movie theatre and home of once-mighty WFBR radio, old Sun stories indicate it was a car dealership and bi-level parking structure erected in 1913 as the Colonial Garage. The horns that sounded here belonged to Studebakers and Ford Phaetons. The Centre Theatre would see its own adaptive-reuse/destruction in 1959 when it was ignobly carved up into offices for the Equitable Trust Company. And now the nonprofit developer Jubilee Baltimore is on the cusp of adapting the structure once again, as creative space—potential studios, classrooms, performance venues—in keeping with the spirit of the Station North Arts District in which it now resides. There’s a lot of history in these walls, and I have about an hour to see it all.

My guide is Jonathan Lessem, a friend and an architect with Baltimore’s Ziger/Snead, the firm charged with reimagining the edifice for the 21st century. He only has an hour to spare for this impromptu look-around, and beyond that, the place is so overrun with mold that you really can’t stomach a longer visit. The air is positively fetid. And it’s pitch black inside. A flashlight’s slender beam is swallowed up by a vast and gloomy squalor. The largest first floor room sports dark granite tiles beneath a layer of filth. This was likely a public lobby area for the bank. A pair of potted plastic plants is a forlorn and surreal addition.

Traces from its garage days are scant, too. Jonathan opens a door and shows me a corner ramp where cars once drove to upper floors. It later became a convenient place for retrofitters to shove air ducts and other mechanical equipment. A 1913 Sun article describes how part of the second floor housed a chauffeur’s lounge, replete with smoking room and billiard tables. (If you were rich enough to own a car back then you were likely loaded enough to hire someone to drive it.) The garage/dealership changed hands and makes of cars sold several times. Early on, a car called a Haynes Light Six was sold here, the onetime motoring pride of Kokomo, Indiana.

The glass block window lighting up a corner stairwell provides the only hint of an earlier 1930s aesthetic. (However, there are plants—real ones this time–growing on the stairs.) A church owned and occupied the rear of the building and walking through its former sanctuary and offices is decidedly spooky because it appears as if the congregation left in a hurry. We’re talking suddenly, and overnight sometime in 2008. They walked away from all manner of office and audio equipment, with Sunday school rooms full of books and half-finished bible lessons on chalkboards. Of course everything is moldy-gross now. It’s amazing what a few years without heat, AC, or a watertight roof can do to a building and its contents.

A backstairs leads us to the truly historic and utterly cool studios of WFBR 1300 AM. A half-moon shaped console festooned with banks of analog meters, lights, and large black dials looks like a steam punk version of spaceship bridge, or perhaps some Dr. Strangelove-era nuclear redoubt. This is the silent, decayed heart of what was once one of Baltimore’s most prominent media outlets. The radio rooms here date to the glamour days of broadcasting, the age of live orchestras and shows such as “Every Woman’s Hour” and “Moonlight in Maryland.” But the station was riding high up through the 1980s. Crazed morning-man DJ Johnny Walker worked here from 1974 to 1987, creating an immensely popular shock-jock shtick long before the likes of Howard Stern. (And Stern’s giggling sidekick, Robin Quivers, worked at WFBR for a bit.) The station broadcast Orioles games between 1979 and 1986, a pretty good run with a World Series in the middle. But the birds flew to another station in ’87, by which time stereo FM already had static-prone AM on the ropes. Walker soon split and the station was sold, ending its days simulcasting an FM station out of Washington—including the Howard Stern Show.

Most of the old equipment here is going to be salvaged, I’m told. Indeed, most of the cool artifacts within have already been tagged for removal prior to the demolition work slated to begin here anytime now. A sun-splashed record library sits silent and empty now, with its ranks of shelving labeled “Greatest Hits” and “Oldies Collection.” I stick my head into a room marked Studio E—and pull it out again in a hurry. Mold and mildew have run rampant on the soundproofed walls and carpeted floors.

In a ramshackle closet full of debris, a reach blindly into a box of old papers to pull out a random sheet to photograph. What I snag is a brief carbon paper dated November 20, 1969 stating that, “Due to Mohawk air crash we deleted one AM and one PM spot.” The airline, you see, crashed a plane into an Upstate New York mountaintop the day before, killing all 14 people on board. I imagine you wouldn’t want jaunty ads promoting an airline’s virtues at the same time that the news carried grim details of a fatal crash. I’ve only heard of Mohawk from AMC’s Mad Men program, where the airline is one of the fictional advertising company’s clients. Indeed, some Mad Men fan blogs have speculated that this very crash might figure in the plot of the upcoming season, which is set in 1969.After a visit to the station’s former lobby/reception area—a study in mid-century modern—we move onward and upward into vast office floors sporting buckling carpet tiles and graffiti. Billions of dollars of bank transactions must have moved through these now decrepit spaces. Only a few rusty vaults provide evidence of their former monetary use. The top floor sports a massive roof failure where sunlight—and mold-engendering rain—enters the building. We can step out on the roof here, right behind the marquee tower, which is revealed to be totally hollow inside. As phony as a movie set.

It’s safe to say my trip up through a century of Baltimore history has been breathtaking, even if sometimes it was a little hard to breath.