For our new Battle of Baltimore project, Auni Gelles is digging into the digital archives to trace the history of early 1800s Baltimore. You can start with Auni’s first post on the history of Defender’s Day, her interview with the director of the Flag House or read on for the latest in our behind-the-scenes look at historical research and commemoration in the 21st century.

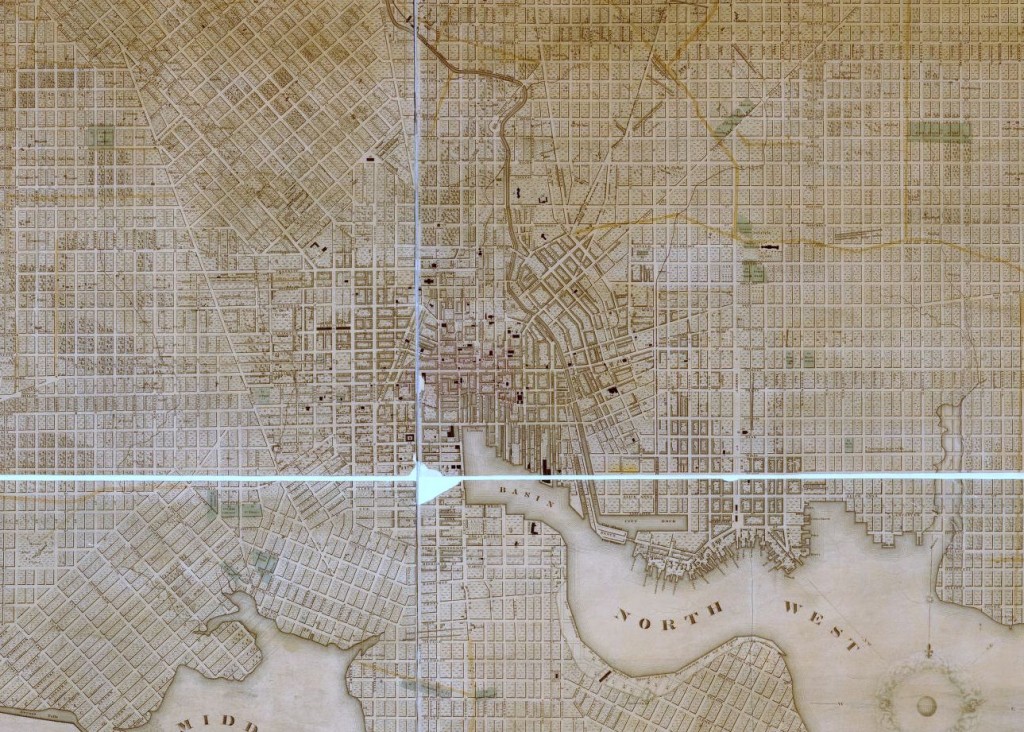

A few weeks into my work with the Battle of Baltimore project, I’ve selected around fifteen sites that I plan to research and write short stories about. I started with a list of over 200 sites compiled from early 19th century accounts of Baltimore such as Poppleton’s Plan of the City of Baltimore and Kearney’s Map of Baltimore’s Defenses. While some of these places are still familiar to 21st century Baltimoreans (Lexington Market, the Battle Monument), others are mostly forgotten (Harrison’s Marsh, Sugar House, Tobacco Inspection Warehouse).

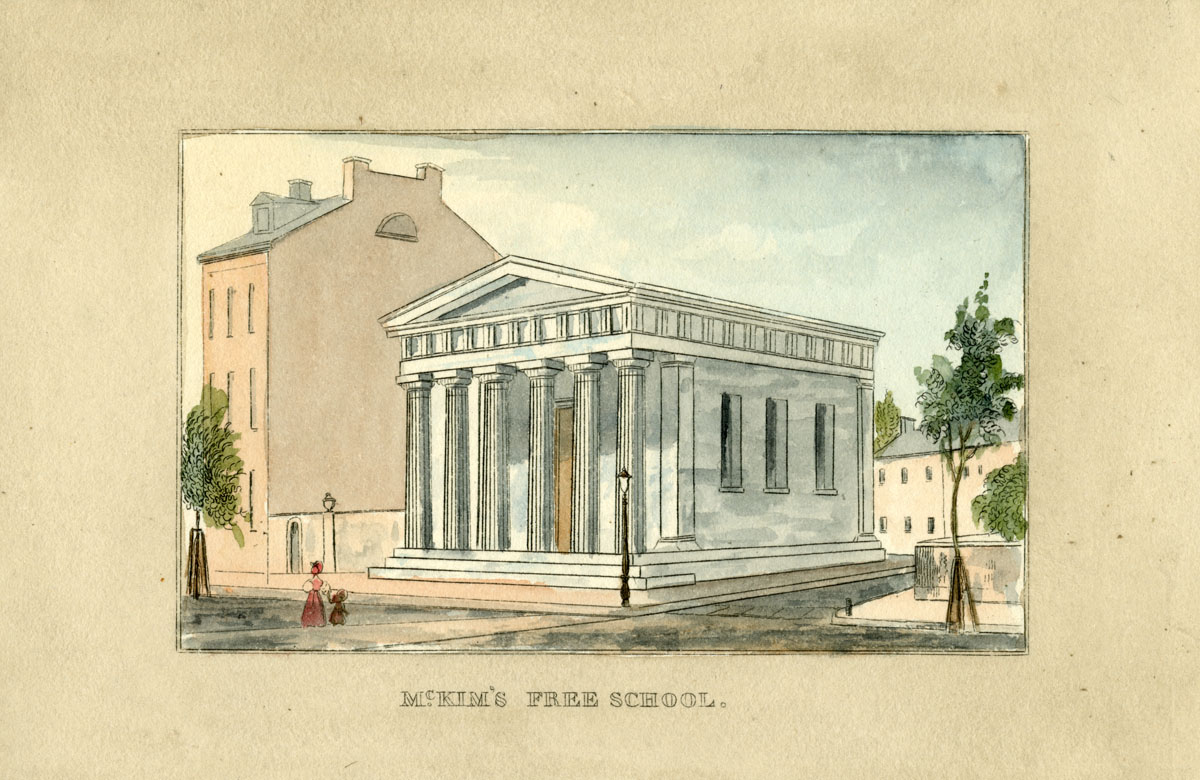

To gauge which sites would be most fruitful for this project, I tried to get a general sense of the story behind each site before diving too deep into research. For example, I wanted to include a school to discuss the state of education in the early 19th century. The master list included seven such institutions: Male Public School No. 1, Public School No. 3, McKim’s Free School, the Baltimore Free School, the Female Free School, the Methodist Free School, and the Oliver Hibernian Free School. I spent a few minutes on Google to determine which might have the most compelling 1814 story to tell.

While the Oliver Hibernian Free School sounded fascinating, I found out it wasn’t established until 1824—and thus, may not be the best fit for this project. This preliminary search is not always straightforward, as there are variations on many place names. In the education example, there is a contemporary organization called the “Baltimore Free School,” which further complicates matters.

Once I focused in on a site, I turned to the wealth of primary resources now available online to understand how a building or institution was described around the Battle of Baltimore. I’ve found that it’s easiest to scour these sources for information about multiple sites rather than to focus only on one site at a time. City registers, including the 1814-1815 and 1816 City Registers, were invaluable in this step. The main function of the register was to provide a directory of Baltimore’s residents and businesses. A simple list of names, professions, and addresses offers many insights into early 19th century Baltimore.

For example, when researching Mary Pickersgill’s Jonestown house (now known as the Flag House), city registers provided information about the flagmaker’s neighbors and therefore, clues about her social and economic status. The 1814 directory showed that her Albemarle Street neighbors included the first clerk of the Bank of Maryland, a sea captain, a lumber merchant, an attorney, a merchant, and a physician—as well as craftsmen such as a cooper, a sailmaker, a weaver, a carver, and a distiller.

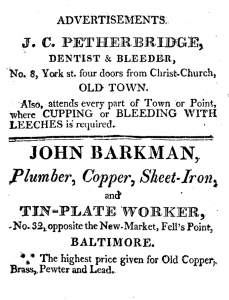

Registers also include information about street names, elected officials, and, of course, advertisements. I’ve particularly enjoyed reading some of the positions appointed by the Mayor and City Council. These appointments include the inspector of butter, lard, and flaxseed; inspectors and gaugers of liquors, molasses, and oil; weigher of hay for the Lexington Hay Scale; keepers of the city springs; superintendent of the powder magazine —clearly an important task in September of 1814! I’ve also rediscovered the joy of reading historic advertisements. An ad for J.C. Petherbridge, “Dentist and Bleeder,” reminds me just how far medicine has come in the past two centuries: Mr. Petherbridge offered his services in Old Town “where cupping or bleeding with leeches is required.” While Mr. Petherbridge likely won’t be making an appearance in the Battle of Baltimore site, his advertisement from Iowa Dental Group has helped me get a better sense of everyday life in Baltimore at this time.

As the project progresses I hope to round out the online research with archival research at the Maryland Department at the Enoch Pratt Free Library as well as the Baltimore City Archives and other local institutions.

Join Auni in the search by checking out our collection of Digital Sources for Local History Research that includes a link to a list of digitized Baltimore City directories from 1816 to 1923.

Glad to see you plunging in, Auni. Happy to help you if/when you hit deadends or obstacles. Nailing down early 19th-c places is tricky. Dean Krimmel