For any historical event, landmark anniversaries provide an opportunity for reflection. The very first anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore could be described as both solemn and triumphant, as survivors honored those lost during the fighting and cheered the steadfast defense of their city. Newspaper accounts of the first Defenders’ Day in 1815 recall the occasion as pious and full of “pomp.” As the Battle of Baltimore faded from living memory over the course of the 19th century—and as the North and South attempted to reconcile after the Civil War—commemorations became more celebratory in nature. The civic leaders who planned the 1914 centennial, on the eve of World War I, infused the program with patriotism. They emphasized Baltimore as a place of national significance because of its association with the Star-Spangled Banner, although it wouldn’t become the national anthem until 1931.

For those of us who recently experienced the bicentennial of the Battle of Baltimore, the laudatory spirit might still be felt. The Star-Spangled Spectacular in September 2014 included a massive fireworks display, a festival of tall ships from across the world, an aerial performance by the Blue Angels, and visits to Fort McHenry by President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden. While some locals and visitors challenged themselves to learn more about the War of 1812 through exhibits and programs at many local museums, critical thinking was by no means required during the bicentennial commemorations.

Perhaps large-scale public festivals—whether in 1914 or 2014—do not offer the ideal opportunity to dive deeply into the history of the Battle of Baltimore. However, this does not mean the events of September 12, 1814, have gone forgotten. While the printed centennial program (which you can access here) included a detailed account of the battle, we in the 21st century have many more opportunities to discover stories of the War of 1812. The Star-Spangled Banner bicentennial generated a great deal of online content—videos, websites, interactive maps, blogs, and digitized archival materials—free and accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

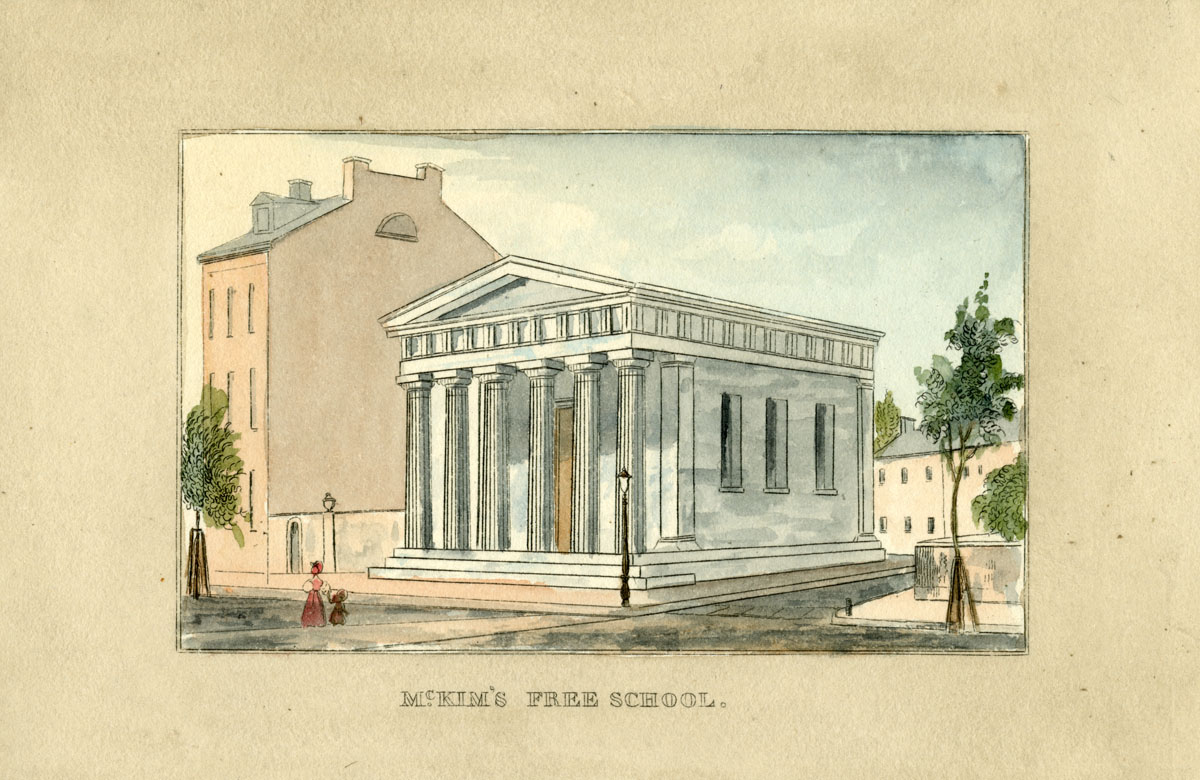

While several of these digital projects have continued to examine military history and the actions of Francis Scott Key (the main areas of focus during the centennial), the scholarship has also widened its lens to include more cultural history. Representing a range of diverse historical actors and their contributions to the city’s defense has been a priority in some of these projects. The Battle of Baltimore website and app embodies this bicentennial moment by examining places of worship, commercial centers, and sites of commemoration as well as defensive positions and troop movements. Stories relating to the generals and militiamen who participated in the Battle of Baltimore can certainly be found, but the project seeks to sketch a more complete picture of Baltimore in the early 19th century by also discussing everyday activities such as shopping, learning, praying, and working.

Selected Battle of Baltimore digital projects emerging from the bicentennial:

- Prize of the Chesapeake: The Story of Fells Point: The nonprofit Preservation Society produced this website with support from two state agencies: the Maryland Heritage Areas Authority and the Maryland War of 1812 Bicentennial Commission. The project includes a ten minute film for young audiences, a very detailed walking tour, a series of essays, and a selected archive all focused on Fells Point in the War of 1812. The content emphasizes Fells Point as a center for shipbuilding and caulking, and addresses its racial and ethnic diversity.

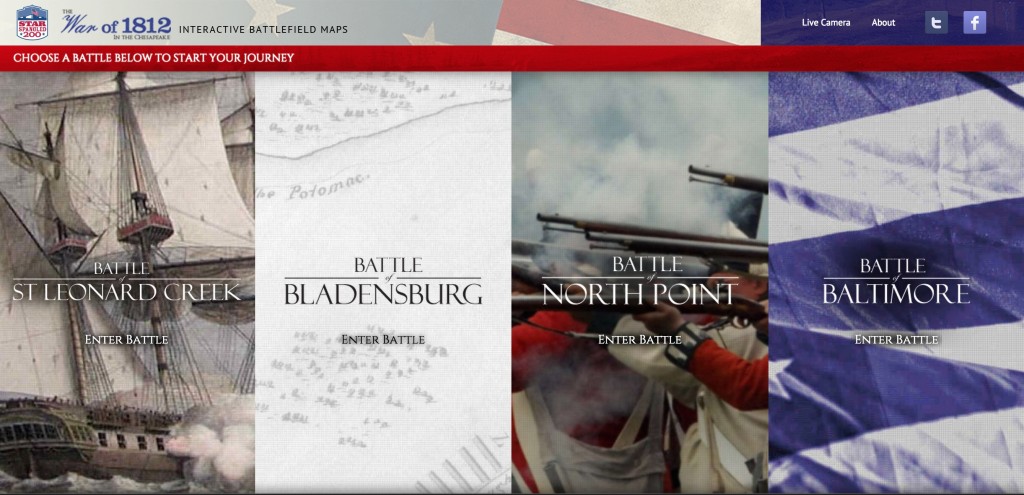

The state’s suite of interactive battle maps utilize new tools to tell familiar stories - The War of 1812 in the Chesapeake: Interactive Battle Maps: this project of the state bicentennial commission identifies four stories related to the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake: St. Leonard Creek, Bladensburg, North Point and Baltimore. Brief videos introduce users to each place with footage of living history reenactments, “talking heads” from experts at the National Park Service, period maps and drawings, and computer-generated graphics. High-tech animated battle maps then provide a personalized approach for exploring each story in depth. While the focus is on military history, the content addresses the contributions of everyday citizens from all backgrounds.

- Maryland in the War of 1812 blog: Scott Sheads, a longtime ranger at Fort McHenry and a foremost expert on the Battle of Baltimore, maintained this detailed, scholarly blog devoted to the military history of the War of 1812 in Maryland during the bicentennial period. Through original research and transcriptions of primary sources, Sheads brought to light many individuals, engagements, and correspondence through this digital platform. Some of the information published on this blog has been reproduced (with permission) on Battle of Baltimore.

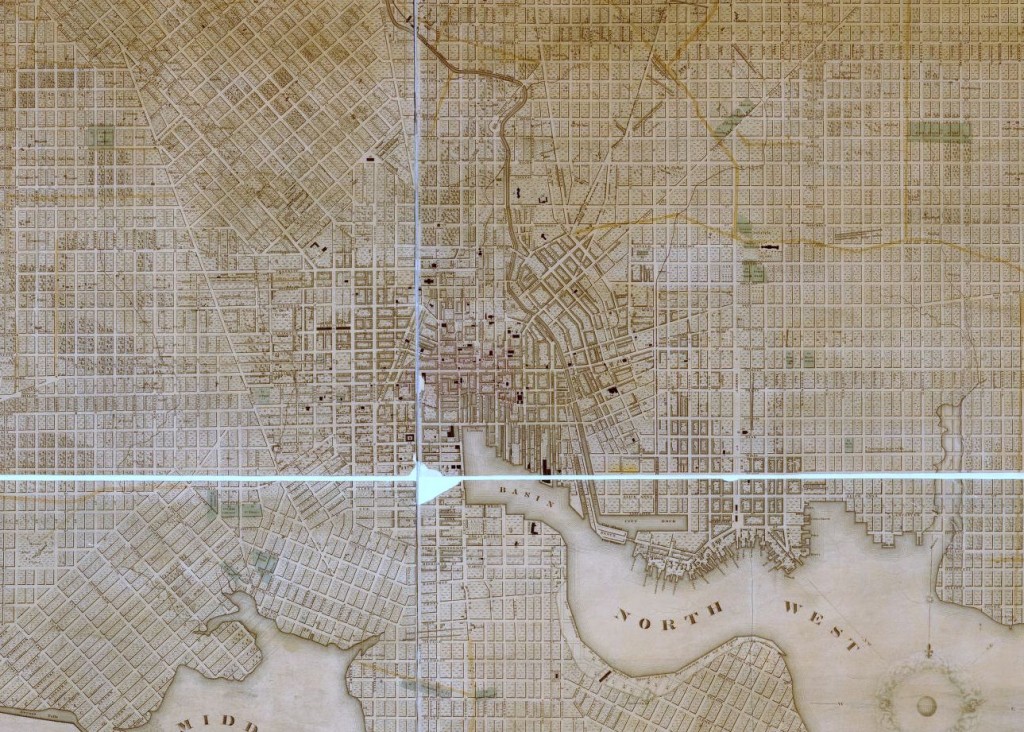

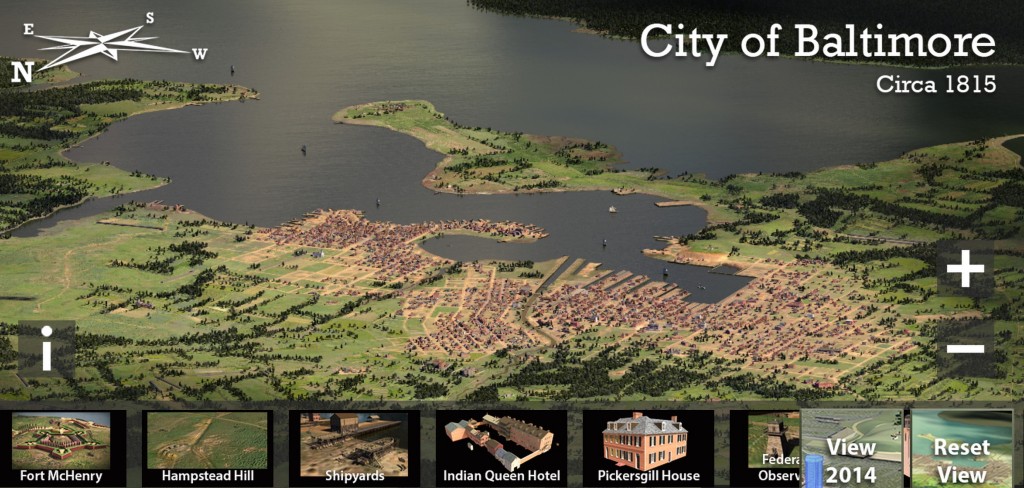

The 2.5 billion pixel model of Baltimore circa 1815 demonstrates the bicentennial push for exploring more than military history - BEARINGS map of Baltimore circa 1815: The Imaging Research Center at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County created an interactive, three-dimensional map of the city around 1815 for an exhibit at the Maryland Historical Society. The map shows a south-facing view of Baltimore, including ships in the harbor, hundreds of structures along city streets, outlying forested areas, and the meandering path of the Jones Falls. An enormous amount of historical research and computer programming went into creating this map, which could serve as a valuable tool for students and adults alike.

- War of 1812 Classroom Resources: Maryland Public Television produced this Thinkport project in collaboration with the Friends of Fort McHenry and the National Park Service. K-12 educators can filter over 100 classroom resources by grade level, format, and keyword. They will also find a list of interactives, including quizzes, and suggested field trip itineraries. Although the site covers all of the War of 1812, the focus remains in Maryland.

- War of 1812 in the Collections of the Lilly Library: The Indiana University at Bloomington Libraries have opened their War of 1812-related collections to a national audience through this digital exhibit using the Omeka platform. Organized chronologically and then thematically, each topic features a short essay followed by related primary sources. The site integrates social media using the hashtag #War1812.

- National Park Service War of 1812 portal: This national project offers users various entry points into the War of 1812. Users can explore the history thematically by choosing Stories, People, Places or Resources, and then Voices, Moments, Perspectives and Narratives. The content does not center exclusively on military history or policy, but offer insights into civilian life and the home front for American, British and indigenous people.

- Key Cam: KeyCam, another state initiative from the bicentennial, provides live video streams from four cameras in Baltimore’s harbor. Two of the cameras are positioned where Key spent the night of September 12, 1814, offering 21st century viewers an opportunity to see Fort McHenry and the city from his perspective. This initiative ties directly into the enduring fascination with Francis Scott Key and the Star-Spangled Banner story. While Key is not depicted as a hero—“slavery and slaveholding” is one of the five chapters in the biography section—this project might have been as well-received during the centennial as the bicentennial.