We recently shared one of our Five Minute Histories videos on Captain John O’Donnell and the early origins of the Canton neighborhood. We asked the question of whether Canton really got its name from O’Donnell, a ship captain who traded in Canton, the anglicized name of Guangzhou, China. And we got the help we needed!

Minutes after we published our video, Baltimore historian Wayne Schaumburg replied with some insight. Apparently we are not the first folks to wonder about this, and a book called Historic Canton by Norman Rukert may shed some light. Here’s the gist of the story.

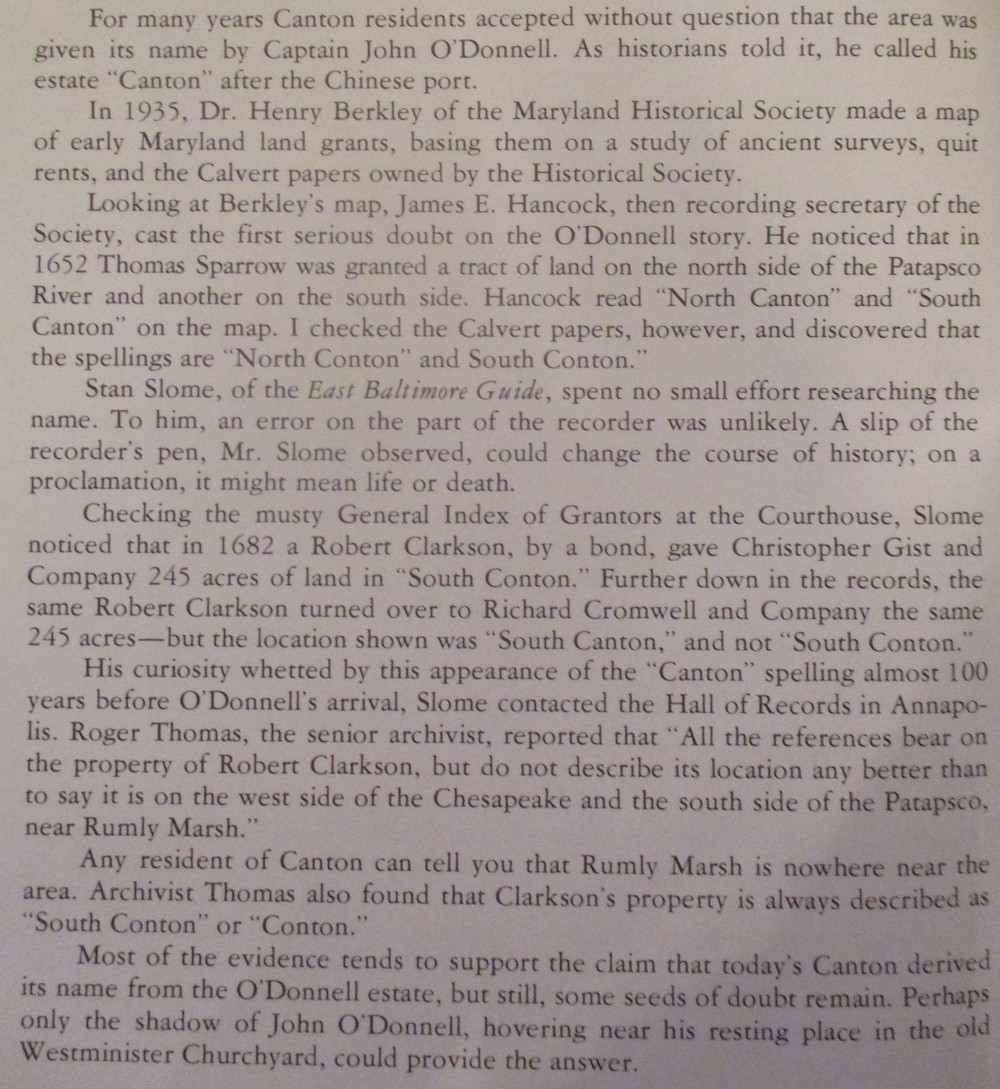

In 1935, two members of the Maryland Historical Society looked into whether Captain O’Donnell was the source of the name Canton. Based on meticulous research, Dr. Henry Berkley mapped out the area into original land grants, quit rents, and Calvert Family papers. His colleague James Hancock looked at the map and noticed that in 1652 (yes, 1652!) there were two parcels near today’s Baltimore that he read as “North Canton” and “South Canton.” This would have been over 100 years before John O’Donnell sailed into Baltimore in 1785 as one of the first American captains to trade with China.

However, the author of Historic Canton, Norman Rukert, didn’t fully believe Hancock’s reading of the word Canton and so he went back to the original Calvert papers himself. He found the parcels were not called Canton, but Conton with an “o” not an “a.” Humm.

To make matters more confusing, a reporter from the “East Baltimore Guide” then took a stab at the original research. He found the 1652 reference to the Conton parcels, and another reference dating to 1682, 30 years later but still way before Captain O’Donnell’s time. In this reference, one Robert Clarkson transferred a 245-acre parcel called Conton and later in the same document transferred the same 245-acre parcel but this time called it Canton. Didn’t anybody teach spelling back then?

Despite the flip-flops in spelling, the final chapter of the saga sheds some light. Upon investigation with the State Archives, the East Baltimore Guide reporter found that the locations of the parcels in question named either Conton or Canton (or both!) are described as on the west side of the Chesapeake and on the south side of the Patapsco near a place called Rumly Marsh. That’s all it took for the intrepid reporter to know for certain that these early parcels had nothing to do with Captain O’Donnell’s land. He knew that although today’s Canton could be described as being on the west side of the Chesapeake, it is certainly not on the south side of the Patapsco and is nowhere near Rumly Marsh.

So, whatever parcels may have been called Conton or Canton in the 1600s, they were not the nearly 2000-acre parcel that Captain O’Donnell amassed in the late 1700s and is today’s Canton neighborhood. We know that the good captain called his estate Canton, and the dogged search through historical records shows he was almost certainly the first one to do so. Case closed, we say!