Two major fires last night in Downtown Baltimore and in Mount Vernon displaced many businesses & workers and have severely damaged several historic buildings. Thanks to the hard work of the Baltimore City Fire Department and other firefighters from across the region, the fires were contained and there have been no serious injuries reported. The buildings affected by the fires include a small row of theaters built following the 1904 Fire and an 1850s former residence that served as the final home of Baltimore Sun founder, A.S. Abell.

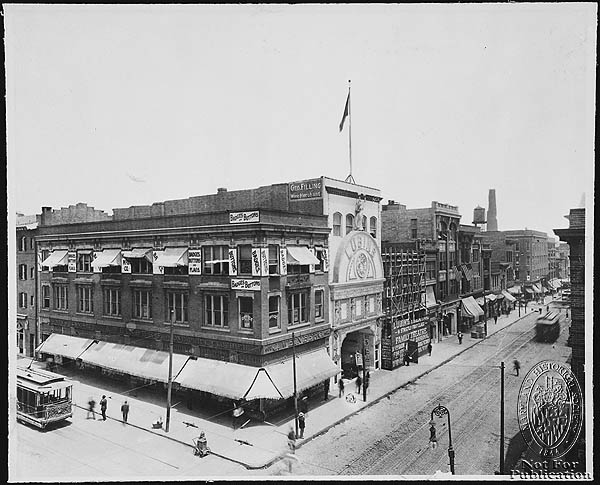

See also a 1987 photo & a 2001 photo of the 400 block of East Baltimore Street.

The four damaged buildings from the Downtown fire are located on the north side of the 400 block of East Baltimore Street, including several contributing buildings within the National Register designated Business and Government Historic District. In the late 19th century, these included the German Bank of Baltimore and several commercial buildings which remained up until their destruction by the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904. The building at the corner of Baltimore and Holiday Streets was rebuilt in 1908 by Pearce & Schenck as The Grand Theater. Next door, Philadelphia film producer Sidney Lubin established the Lubins Theater which later became the Plaza and, more recently, Gayety Show World.

The two damaged buildings in Mount Vernon on the west side of the 800 block of North Charles Street are contributing buildings within the Mount Vernon local and National Register designated historic district and date from the early 1850s. The four-story building located at the northwest corner of Charles and Madison Streets is particularly significant as the former residence of A.S. Abell, the founder of the Baltimore Sun. Abell purchased the building from the Kremelberg estate in 1883 and remained in the home up until his death on April 19, 1888. A 1912 description of the home noted, “The house is a four-story marble and brick building, which included about twenty-five rooms, and a magnificent winding staircase in the center of the dwelling, which towers to the roof, and in itself gives an idea of the elaborateness of the structure.” (More.)

For us at Baltimore Heritage, we are particularly saddened by the damage to the offices of noted preservation architects Murphy & Dittenhafer, located at the top floor of the former A.S. Abell residence, and specifically for our board member Matthew Compton who is an architect with this firm. As Downtown and Mount Vernon work to recover from these fires, we plan to support efforts to preserve and restore the damaged buildings.