Explore the stories of Gothic Revival churches, grand Victorian mansions with unrivaled architecture, peaceful tree-lined paths, and more landmarks from Harlem Park and Franklin Square.

In the decades before and after the Civil War, Baltimore grew at a lightning pace as thousands of European immigrants and migrants from the South arrived in the city. Many wealthy locals left behind the crowded blocks around downtown and moved out to the handsome park squares in West Baltimore.

In the decades before and after the Civil War, Baltimore grew at a lightning pace as thousands of European immigrants and migrants from the South arrived in the city. Many wealthy locals left behind the crowded blocks around downtown and moved out to the handsome park squares in West Baltimore.

Lafayette Square

Lafayette Square has long been considered the height of fashion. Established in 1857 on a high ridge, early visitors enjoyed breathtaking views of West Baltimore’s rolling hills dotted with country mansions. Early efforts to develop Lafayette Square as a neighborhood halted when the Civil War began in 1861. Union troops cut down the park’s old trees to build the Lafayette Barracks. After the war, the city restored the park and the neighborhood grew with churches and homes that soon started to pop up around the Square.

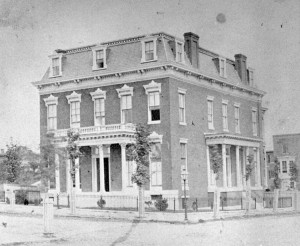

Sellers Mansion

In 1868, Baltimore railroad magnate Matthew Bacon Sellers, Sr. commissioned architect Edward Davis to build a brick mansion for his family. Although badly deteriorated today, the quality of craftsmanship and detail rivaled similar suburban homes of its day. Sellers’ son Matthew Bacon Sellers, Jr. (born the year after the house was built) became a founding member of the Aeronautical Laboratory Commission (precursor to NASA). The home remained in the family through the 1950s. It later housed Operation CHAMP—an innovative recreational program that served thousands of West Baltimore youth from 1967-1980.

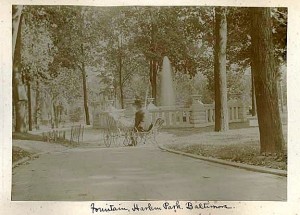

Harlem Park

In 1876, the heirs of Dr. Thomas Edmondson donated 9 ¾ acres of his estate to create a new city park. Named “Harlem Square,” the park was double the size of Franklin Square or Lafayette Square. The landscaping featured beds of colorful flowers laid out in patterns of stars, diamonds, hearts, ovals, and circles. Despite the neighborhood’s distance from downtown, the attractive park and builders like Joseph Cone promoted the development of rowhouses in the area. In the early 1960s, the construction of a school took half of the park to make a schoolyard.

Harlem Theater

The Harlem Theater – a premier destination for West Baltimore’s black moviegoers – once boasted a 40-foot high sign with 900 light bulbs visible from two miles away. The Fidelity Amusement Corporation, which ran the theater, counted over 5,000 attendees during its opening weekend in October 1932. Originally built as the Harlem Park Methodist Episcopal Church in 1902, the building became a church again in 1975 when Reverend Raymond Kelley, Jr. turned it into the Harlem Park Community Baptist Church (which continues there today).

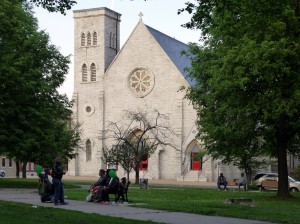

St. Luke’s Church

A true gem of Baltimore religious architecture, the handsome Gothic Revival tower of St. Luke’s Church is matched by its richly detailed sanctuary. While architect J.W. Priest oversaw the completion of the building in 1857, five other architects also played some part. Unlike many historic congregations that left the neighborhood, St. Luke’s opened its doors on July 10, 1853 and has kept them open for over 150 years.

Franklin Square

On a single Sunday in the spring of 1850, over 3,300 locals came to stroll around Franklin Square, one of Baltimore’s oldest parks. The park was originally part of Fayetteville, Dr. James McHenry’s country estate. McHenry had served as the nation’s first Secretary of War to George Washington and John Adams before retiring in 1800. In 1835, James and Samuel Canby, speculators from Wilmington, Delaware, purchased 32 acres of land from Dr. McHenry’s heirs. Four years later, the pair sold 2.5 acres to the city (for just $1) to establish Franklin Square.

Waverly Terrace

Named after Sir Walter Scott’s 1814 novel Waverly, Waverly Terrace reflects the wealth of Franklin Square’s residents in the 1850s. The Baltimore Sun praised architect Thomas Dixon’s four-story row as “much handsomer than any yet finished in this city.” Matching the area’s current diversity today, residents in the early 1860s included both Confederate sympathizers (Miss Nannie, Miss Virginia, and Miss Julia Lomax, charged with disloyalty by Union troops) and African-Americans (Lloyd Sutton drafted for the U.S. Colored Troops).