Race and Place in Greater Rosemont is a short history of the Evergreen Lawn neighborhood written by Dr. Ed Orser, with contributions from Kirin Smith and Dr. John Bullock, and edited by Linda Shopes. This essay was produced for the Race and Place in Baltimore Neighborhoods program series (2010) supported by the Maryland Humanities Council.

Dr. Orser’s essay takes readers on a walk through the neighborhood allowing visitors and residents to West Baltimore to retrace the steps of our 2010 tour and understand the history of race and place in Greater Rosemont.

Introduction

The Greater Rosemont area of West Baltimore owes its name to the expressway battle of the 1960s and 1970s that a Baltimore Sun reporter once called “Baltimore’s Vietnam.” The projected route threatened neighborhoods where African Americans only recently had gained housing opportunity by breaking down racial barriers that had prevailed for so long.

A half century earlier, this area had been Baltimore’s western edge, as rowhouse construction filled up the formerly rural district. New development created residential opportunities for working and middle class Baltimoreans in streetcar suburbs on the city’s western edge–but on a whites-only basis. When residential restrictions began to tumble in the early 1950s, racial change proceeded at a rapid rate. Within only a few years the formerly all-white area had become virtually all-African American. New housing opportunity provided the basis for home ownership, the establishment of institutions, social activism, and community pride.

While this legacy continues, sixty years later Greater Rosemont illustrates not only the resilience of these neighborhoods, but the challenges that characterize many older parts of the city today. Unquestionably, Greater Rosemont is a part of the city whose history illustrates the role of “race and place.”

[su_button text=”Greater Rosemont Tour Map” url=”http://exhibits.baltimoreheritage.org/neatline/fullscreen/race-and-place-in-greater-rosemont” type=”info”]Explore Greater Rosemont with our tour map and timeline![/su_button]

West Baltimore MARC Station

Today, the parking lot of the West Baltimore MARC Station and the concrete highway lanes to the east dominate this site, symbols both of the weight of the past and prospects for the future.

Relocation Action Movement and the Movement Against Destruction

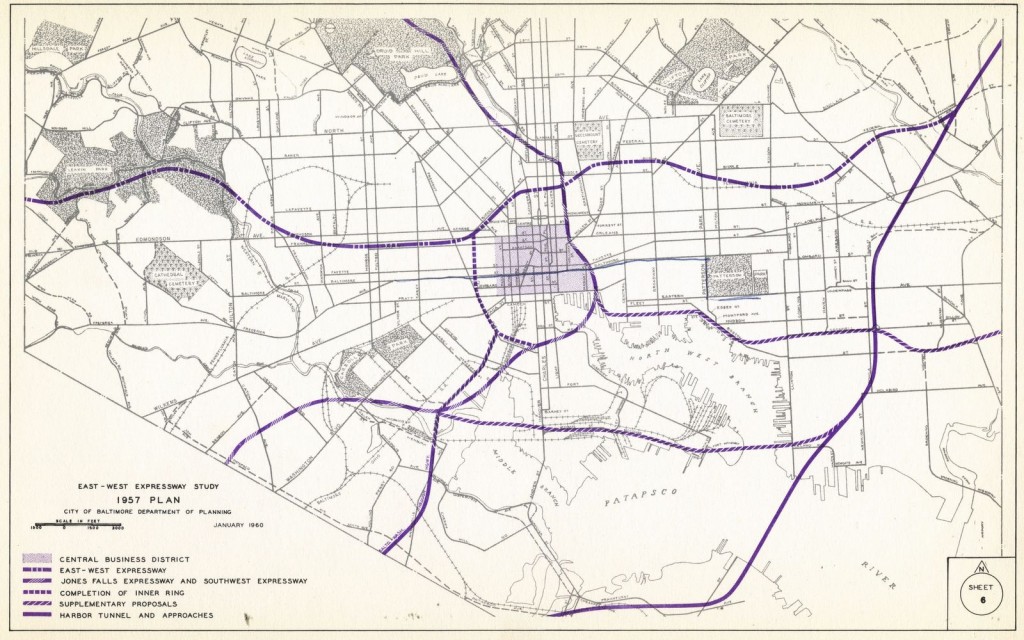

In the 1970s major demolition occurred in the corridor to the east to build the first leg in a proposed East-West expressway, envisioned as the eastern extension of Interstate 70. The route was to proceed west along a corridor directly through the Greater Rosemont communities and continue on through the heart of Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park. African-American residents in this section of the city fought the road plan under the banner of RAM (Relocation Action Movement). The organization joined with city-wide expressway opponents under the umbrella of MAD (the Movement Against Destruction), a coalition that cut across lines of race, class, and differing interests in opposition to various sections of the proposed expressway system.

In the late 1960s, houses along the corridor to the west of this site were condemned by the city for the proposed highway. However, mounting protests initially forced the decision to designate an alternate route and eventually to abandon the section through Greater Rosemont and the parks to the west altogether. Soon, the one-mile stretch of expressway that was completed with such controversy and such cost—economic as well as social—was being called “The Road to Nowhere.”

Recently, city and state transportation officials have been developing plans for an east-west light rail line to provide more effective mass transit options and to complement the existing north-south commuter rail lines. The proposed route would bring this new light rail line along the Route 40 corridor—in part the former East-West expressway alignment—with the MARC (Maryland Area Regional Commuter) train station envisioned as an important transportation hub. A number of local leaders have formed a coalition as advocates for the plan, contending that the light rail not only would provide much-needed transportation options for area residents, but also could spur transportation-oriented development (TOD) and serve as a catalyst for revitalization. They have organized as West Baltimore TOD/Transportation, Inc., to make sure that their voices are heard so that transportation planning, which once did such damage to this part of the city, can result in better outcomes this time. The group has initiated several projects designed to call attention to the site and provide services to the neighborhood, including a seasonal farmers’ market.

Along Gwynns Run

The topography of this vicinity is shaped by two branches of the Gwynns Run, a tributary of the Gwynns Falls. They created this valley and the next, over the hill to the west. Both are now completely covered in underground conduits. Braddish Park, extending north from Edmondson Avenue, provides green space and play area in the valley formed by the western branch.

In 1852, Baltimore extended its official western boundary to a line near this site, and dense rowhouse development spread to this vicinity from the city center. Italianate rowhouses, visible along Franklin and Mulberry streets, with front steps directly on the sidewalk and flat roof-line cornices, illustrate this period. In 1888, Baltimore City annexed Baltimore County land west to the Gwynns Falls Valley, setting the stage for new waves of urban growth. Development followed the trolley lines, like the one along Edmondson Avenue to Poplar Grove Street, where a cluster of settlement occurred first. By 1900, the area between the old city line and Poplar Grove was ripe for residential development, delayed until then in part because of complications with land titles. During the next several decades rowhouse builders developed street after street, and Greater Rosemont took on the physical character it has to this day.

The presence of the railroad line connecting Baltimore and Washington—originally the Pennsylvania Railroad, today Amtrak—attracted commercial operations that depended upon rail connections, like warehouses, stockyards, and the substantial brick American Ice Company, built in 1911 just to the north of this site. These establishments provided employment for some area residents.

North Warwick and Lauretta Avenues

Racial Change

As late as the early 1940s, the racial boundary on the city’s west side, underwritten by both formal and informal mechanisms of discrimination, lay east of here along Fulton and Pulaski streets. But in the early 1950s, substantial racial change from white to African American occurred in this vicinity, and the imposing church structures ahead, along North Warwick Avenue, serve as significant markers of the speed and scale of this process.

In a remarkably short period of time, virtually all of the neighborhood’s formerly white churches relocated to the western edge of the city and beyond, following the path already taken by their parishioners. The African American congregations that acquired their existing facilities were themselves making a westward move from older, segregated parts of the city, establishing an important institutional presence for the area’s new black residents.

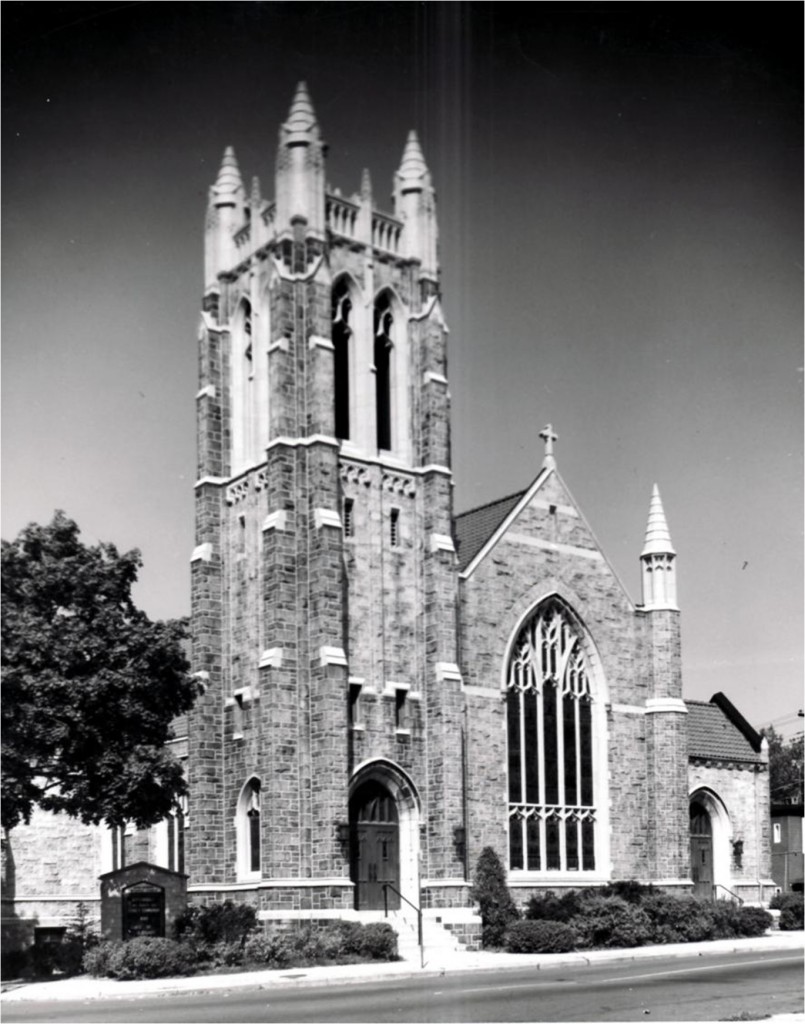

The granite edifice in Gothic Revival style that anchors the northwest corner of Edmondson and North Warwick Avenues, serves the African American congregation of Perkins Square Baptist Church, which acquired the building in the mid-1950s. The structure was built in 1913 for Emmanuel English Evangelical Lutheran Church to serve the then growing white rowhouse neighborhood. A block north, at the corner of Arunah Avenue, today’s First Abyssinia Baptist Church occupies the former site of the Arunah Brethren Chapel (also known as “Gospel Hall”). The white church closed in 1951, and the African American congregation acquired the site in the early 1960s, constructing a new building in the 1980s. A block farther, on the northwest corner of Harlem Avenue, the tall steeple of the stone Gothic Revival-style Union Memorial United Methodist Church looms over nearby residences. Built in 1925-1926 for Harlem Park Methodist Episcopal Church, this church remained Methodist, but exchanged congregations from white to African American in the mid-1950s.

Both the dates of church transition, all occurring in the early to mid 1950s, and the direction of relocation were significant as indicators of the area’s changing racial demographics. Emmanuel Lutheran and Harlem Park Methodist moved a full five miles west to the Catonsville area, as did two other neighborhood churches, while the Perkins Square Baptist and Union Memorial Methodist congregations came from sites a mile or so to the east.

Other evidence also marks the process of dramatic racial residential change. A July 1950, article in the Baltimore Sun identified a house in the 2300 block of Lauretta Avenue (near this spot) as the newly-acquired home of Beatrice Simmons, the first African American resident in the neighborhood, and cited an instance of vandalism that greeted her arrival. While incidents of overt hostility sometimes occurred in the process when blacks moved in to a formerly all-white district, the Maryland State Commission on Interracial Problems observed that more typical was what it called “the frigid withdrawal” of whites. U.S. Census figures, registered every ten years, cannot document the moment of change, but they do attest to its scale. In 1950, only 89 African Americans resided in this part of the city (census tract 1605, bounded by Pulaski, Franklin, Braddish, and Laurens); ten years later, there were only 143 whites.

The Expressway Battle

This corner lies in the center of the corridor between Franklin Street and Edmondson Avenue where Baltimore officials condemned 880 houses for the proposed construction of the East-West Expressway in the late 1960s, little more than a decade after African Americans had seized the opportunity to acquire homes in neighborhoods formerly closed to them. Witnessing the process immediately to the east where condemnation already had occurred (and demolition was imminent) for the artery to be built between Franklin and Mulberry Streets, Greater Rosemont residents became active in the Relocation Action Movement, which united with others opposing various sections of the proposed expressway system across the city under the banner of MAD.

Baltimore in 1968

In April 1968, civil disturbances convulsed the city in the aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., adding to the general climate of heightened social tension between Baltimore’s citizens and its officials. For RAM, the highway threat was a civil rights issue. As an example, when the group’s proposal for an underground roadway to spare residences was rejected on the grounds that it would be too expensive, a member exclaimed, “It always has been expensive to operate a segregated society.” James Dilts, in a series of articles in the Sun that year, decried the logic of the expressway plan, which he believed amounted to destroying parts of the city and harming its residents, even as it promised to improve the city.

Late in 1968, mounting opposition to the Greater Rosemont route led Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro, III, to propose an alternative that would bypass the affected neighborhoods by following a route along the railroad line to the south. However, the following year, when the city announced a plan to sell the formerly condemned houses back to their original owners, only half took up the offer, the remainder having decided to move out for good. A 1970 Sun article referred to Rosemont as “a once stable middle-class Negro community which was devastated by plans to build the East-West Expressway through its core.”

North Warwick and Edmondson Avenues

After Baltimore’s annexation of part of Baltimore County in 1888, this neighborhood’s first substantial residential construction occurred along the Edmondson Avenue streetcar route in this vicinity when John McIver and John F. Piel began building rowhouses in 1906. Advertising the development as “Edmondson Terrace,” they adopted the new Artistic rowhouse designs of the era which departed from the Italianate style, predominant until the turn of the century. Instead of the straight cornice and flat fronts of the earlier Italianate type, these Artistic-style rowhouses are characterized by decorative roof lines, three-sided bay fronts, a continuous line of porches, and small front yards (some along here now converted to concrete sidewalks).

Residents of the district annexed in 1888 were promised improved city services in return for the city’s higher taxes. One reminder of this arrangement was the early establishment of Fire Engine House #36, located two blocks to the east of here at the southeast corner of Edmondson Avenue and North Bentalou Street. Built in 1910 of brick with stone trim in Tudor style, it celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2010.

Wheeler Avenue at Arunah, Harlem, and West Lanvale Avenues

Edmondson Terrace Improvement Association

Through the 1920s, John Piel, operating as the Piel Construction Company, built additional Artistic-style housing along east-west Edmondson, Arunah, and Harlem avenues and West Lanvale Street, between North Bentalou (a block east of here) and Whitmore Avenue (two blocks west). Rowhouses erected during the latter stages of his company’s construction adopted the new “daylight” configuration, which gave each room an outside window. Many of these houses featured either half-story bays above the porch or full-story bays to the side of the porch, as well as front yards.

White residents formed the Edmondson Terrace Improvement Association. The organization acted to protect the predominantly residential area from commercial and industrial development by supporting stricter city zoning measures. It also sought to maintain the racial and class homogeneity of the neighborhood. For example, in the 1920s the association, like similar organizations in the city, admonished white homeowners not to sell to African Americans. During this period a variety of institutional practices–zoning, restrictive covenants, and “redlining” (the last restricting the availability of mortgages)–combined with individual prejudice to undergird very rigid patterns of residential segregation.

In the years following World War II, the walls of residential segregation on the west side began to tumble, then collapse, as population growth, civil rights activism, legal victories, and changing real estate practices challenged traditional restrictions. By the late 1940s African Americans were pushing the boundaries of residency westward, and whites responded by flight. Within only a few years the trickle of relocating residents had become a flood. The result of this very rapid process typically was not racial integration, but re-segregation.

Evergreen Protective Association

An indication of the early stages of the process in this part of the city was a 1949 society column in the Baltimore Afro-American in which the author wrote of a “change-the-address game,” naming prominent members of the black community who now resided near here on streets like North Bentalou and Baker:

“What with the local yokels forsaking the ghettos and moving into swankier mansions, it takes a special edition of the directory to locate your best friends these days.”

In 1950 and the years immediately following Baltimore Sun classified ads signaled that substantial racial change was underway. Suddenly, houses listed for sale in this vicinity (with North Bentalou, Wheeler, West Lafayette, Calverton Heights, and Lauretta avenue addresses) were designated as “colored”—often with the additional stipulation that they were “vacant,” presumably indicating their white owners already had left). The first wave of new settlers came from the more advantaged sectors of African American society, members of a growing black middle class. In 1960, at the end of a decade characterized by nearly total racial residential turnover, the median income of households in the census tract was slightly above the median for Baltimore City as a whole, and seventy–three percent of households were owner-occupied homes.

Current residents testify to the strong sense of pride of ownership and middle-class status that characterized the Evergreen community that emerged from this period of racial change. As early as September 1951, new African American residents organized a neighborhood association of their own, the Evergreen Protective Association, to “promote good citizenship,” a goal mirroring the aspiration of the Edmondson Terrace Association that had preceded it. The organization, still active today, sought to assure property upkeep, foster social interaction, and protect the neighborhood from perceived threats. On the latter front, the association and its members played an active role in the fight over the expressway. In more recent years, as the neighborhood has been faced with declining levels of social and economic stability, its activities have included cooperation with a campaign to curb drug traffic and crime on the west side of Baltimore.

Wheeler Avenue at Calverton Heights and West Lafayette Avenues

Daylight rowhouses, set back from the street and featuring green tile mansard roofs and flat fronts in Georgian Revival style, extend along Calverton Heights and West Lafayette avenues in this vicinity. Theyare characteristic of dwellings erected in several parts of the city’s westside in the early 1920s by George Schoenhals. As one Schoenhals ad boasted, the “distinctive homes” featured “stone porches, concrete floors, Terrazzo steps,” with “six rooms, tiled bath, hot-water heater, hardwood floor, twentieth century decorations and attractive electric features; modern throughout.”

A number of clues point to the strong element of German heritage among early settlers of the Evergreen neighborhood. Schoenhals himself was active in the city’s German organizations. Moreover, several of the early local congregations had German roots, including Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Arunah Brethren Chapel, and Immanuel Reformed Church (on North Bentalou Street; today St. Mark’s Institutional Baptist Church, an African American congregation). However, at the time they were established a distinctive German identity already was rapidly giving way to assimilation to mainstream American ways; as one example, even before Emmanuel Lutheran relocated to Evergreen, it included “English” in its official name to signal the language of its services.

Blocks in this section of the neighborhood, known locally as “Goose Hill,” were developed relatively late. A 1923 article in the Sun attributed the delay to the relative distance to streetcar lines, the nearest being along Edmondson Avenue. Prior to that time the land served annually as the circus grounds, with convenient access to the nearby rail lines, but the encampment had been pushed northward by residential development, a block at a time. The Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity (at the corner of West Lafayette and Wheeler avenues) and James Mosher Elementary School (a block farther north, at the corner of Mosher and Wheeler avenues) were both built on land described as “the former circus grounds” when acquired in the 1920s.

Wheeler Avenue and Mosher Street

The neighborhood lacked a local school until James Mosher Elementary (#144) was built in 1933. The original brick structure, facing Wheeler Avenue, was constructed in simple Art Deco style. In an era of segregation, it was designated a “white” school; children still were required to travel outside the neighborhood for junior high and high school.

In the early 1950s, Baltimore school officials were described as stunned by the scale and pace of racial change on the west side. A September 1952, Sun article reported a spokesperson as saying that “Baltimore never has known anything such as the population shift within the summer months.” The reporter went on to write:

“The ingress of Negro home owners and dwellers in hitherto white neighborhoods in northwest and northeast Baltimore during the summer months has presented a problem which is bound to perplex the School Board until some kind of relief can be obtained either through construction of new facilities or through the use of portables.”

School #144 was specifically identified as one of several schools where there had been “tremendous turnover” from white to black. By 1953, James Mosher—by then designated officially as a “colored” school—was reported to be tremendously overcrowded.

James Mosher Elementary School after Brown

In 1954, immediately following the Supreme Court ruling that school segregation was unconstitutional, Baltimore public schools became the first formerly segregated major urban system to adopt a desegregation policy–but the change had little practical effect on schools already virtually all-black like James Mosher. In 1955 a much-needed addition was completed along Mosher Street in contemporary architectural style. By then school enrollment had surpassed 900, up from less than 400 a few years earlier.

Two new schools, built nearby in the 1960s, provided further evidence of the dramatic growth in the area’s school-age population. In 1960, Calverton Junior High was constructed on the western edge of the neighborhood. The massive complex housed four nearly self-contained units, each conceived as a “school within a school.” In 1963, Lafayette Elementary School was built, also on the west side. It closed as a standard elementary school in 2003 and reopened as the Empowerment Academy, a public charter school.

Mosher Street and North Warwick Avenue

Rowhouses on three quadrants of this corner illustrate distinct periods of development. On the northwest corner, rowhouses west on Mosher (as well as duplexes to the north along Warwick) are among the area’s oldest. They date to the late nineteenth century, when they stood as an isolated residential island, probably serving those who worked in such nearby operations as quarries, industries, and railroads. On the southeast corner are 1920s daylights built by Schoenhals with their characteristic green tile mansard roofs. And on the southwest corner are the functional plain fronts of daylight rowhouses, among the last to be built in this area in the early 1950s. (A block to the north, along Riggs Avenue, is yet another rowhouse variation; built in the 1940s with a streamlined design, the units step down from one to another to accommodate the contour of the hillside.)

Visible to the north, are the brick multi-family Winchester Apartments, built with Federal Housing Authority financing in the late 1960s to provide affordable housing opportunity. Just beyond the apartments is the wooded boundary of the Roman Catholic-affiliated St. Peter’s Cemetery. It was established in the nineteenth century by the working class Irish parish of St. Peter the Apostle Church in the Hollins Market area, near the B&O Railroad shops where many parishioners worked. Today, it maintains a connection with St. Peter Claver parish at 1546 North Fremont Avenue, which has served the African American community for more than a century. In recent years the groundskeeper’s dwelling has been occupied by Jonah House, whose residents are committed to activism on behalf of peace and social justice.

North Warwick Avenue and Harlem Avenue

The stone tower of Union Memorial Methodist Church at the corner of North Warwick and Harlem avenues marks the last tour stop, and some final reflections on Evergreen and Greater Rosemont are in order.

In recent decades Evergreen’s socioeconomic status has remained rather strong, but the Rosemont area as a whole has seen relative decline. In 2000 home ownership in Evergreen stood at a very high 78 percent, but in the surrounding area (U.S. Census Tract 1605) it was less: 63 percent. Similarly, while median household income in Evergreen that year was close to the citywide level, the figure for the tract was 20 percent below it. This pattern of declining economic status for the tract as a whole was already evident in 1980, when 21 percent of households there were below the poverty line. More recently, for Evergreen the percentage was 16 percent in 2000. Evergreen residents have a somewhat longer tenure than those in other city neighborhoods; in 2000 the median household owner had moved into the neighborhood in 1971, nearly three decades earlier.

2500 block of Harlem Avenue

The Baltimore Afro-American in 1967 called the 2500 block of Harlem Avenue (which extends west from the church) ”a typical slice of Baltimore”:

The 2500 block of Harlem Avenue is a microcosm of middle-class Baltimore. . . . A visit to the neighborhood on a late summer afternoon caught the block in a typical setting. The tall, majestic greystone Union Memorial Church dominates the northwest corner of Harlem and Warwick Avenues. The row homes are separated from the tree-lined streets by carefully tended shrubbery and small neatly trimmed plots of lawn. . . . .

Warren Peck, at 2507, is an arts and crafts teacher for the Department of Education . . . . He has lived in the area since 1952 when he was discharged from the Army [as a World War II and Korean War veteran]. . . .Like most of the residents in the block, he is a native Baltimorean. . . . He worked as a Pullman porter for several years before he was drafted into the army, and later returned to the railroad. “There was good money in those days,” Mr. Peck maintains. As a matter of fact, it was primarily money saved up from his railroad work that enabled him to buy the home in 1952, he said. He paid $11,500 for the house when the neighborhood was undergoing a racial change. . . . Mr. Peck is one of 11 teaches living in the 2500 block of Harlem Ave. Among the residents are at least two ministers, a nurse, two proprietors of beauty salons, three Social Security Administration employees, and a number of retired persons.

The article reported the statements of one of the only two white residents who remained on the block in 1967:

Miss Julia Knoerr has lived with her two bachelor brothers there since 1926: “The real estate people used to call me all the time, but I settled them–I made it clear that I didn’t intend to move anywhere. . . . I thought it was silly the way people began to move out [in the early 1950s], but some people will complain about anything.” . . . Contrary to claims of opponents of fair housing who say property value drops when integration comes, Miss Knoerr believes that property values have improved in the block over the past 15 years. “Everybody takes more interest in keeping their places nicer than people used to,” she noted.”

Dr. J. Welfred Holmes, a Morgan State College (now University) professor of English lived at 2559 Harlem Ave. from the early 1950s to his death in 1968. The obituary in the Sun noted that he had earned his Ph.D. at the University of Pittsburgh, then taught at several historically black colleges before coming to Morgan in 1946. One of the co-founders of the Evergreen Protective Association, he also was active in Baltimore Neighborhoods, Inc. (a fair housing advocacy group) and the American Civil Liberties Union.

Indeed, the 2500 block of Harlem was quite a block! And it is a fitting place to end our tour.