Learn more about the Falls Road Roundhouse preservation issue.

The 1910 Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad Roundhouse is an often-overlooked landmark on Falls Road just north of the Baltimore Streetcar Museum. The Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad, known as the Ma & Pa, connected Baltimore, Maryland and York, Pennsylvania, over a circuitous seventy-seven mile route. In 1881, the Falls Road site became the Baltimore terminal for the Baltimore & Delta Railway (a predecessor of the Maryland & Pennsylvania) originally including a wood frame roundhouse. The original roundhouse burned down in 1892 and, in 1910, the railroad rebuilt the substantial stone building that stands today. The Ma & Pa thrived in the 1900s and 1910s providing regular commuter service between Belair and Baltimore, country excursions for city residences, and milk and mail delivery between Baltimore and Pennsylvania.

Two years after the Ma & Pa ceased operations in 1958, the city purchased the roundhouse and the terminal complex. For the past 55 years, Baltimore City has used the site for truck parking and winter road salt storage. This is a contextual history of the Ma & Pa Roundhouse and a broad review of the changing context of the Jones Falls Valley and the conversation around the future of the roundhouse and other natural and historic resources within the corridor over the past 50 years.

[toc]

Early Development: 1867-1901

Maryland Central Railroad chartered in Maryland – 1867

In 1867, the Maryland state legislature chartered the Maryland Central Railroad to build a line from Baltimore to Philadelphia through Bel Air and Conowingo – making the business the earliest predecessor of the Ma & Pa despite the enterprise never building even a single section of track. [1] Over the next decade, three more railway companies won charters to build a railroad northeast from Baltimore but none managed to lay any track.[2]

Baltimore and Delta Railway organized – 1878

Finally, in 1878, William Waters and a group of Harford County investors consolidated the charters of several failed companies to form the Baltimore and Delta Railway. Their modest goal was to build a local rail line carrying slate from Delta quarries, milk (and other agricultural goods) from country farms to Baltimore markets. Hoping to connect with the Peach Bottom Railway at Delta, the B&D Railway built a narrow gauge line. [3]

A narrow gauge line is any railway built with the rails closer together than the “standard” gauge. The standard was set at 4’ 8 1⁄2” space in Great Britain in 1840s and carried over to the United States. In comparison to standard gauge, narrow gauge railways could be built with lighter rails and tighter curves with smaller engines and garages – all making the Baltimore & Delta and other narrow gauge railways more affordable to build, equip, and operate.

Baltimore & Delta Railway builds Baltimore terminal – 1881

By early August 1881, the company had sold $140,000 in bonds financing the start of construction on the Baltimore terminal below the North Avenue Bridge and laying track near Lake Avenue. The Sun reported that the railroad had already:

“…purchased 20,000 cross-ties. They have also purchased of the Cambria Ion Works, Pennsylvania, 500 tons 40-pound steel rails, of the Jackson & Sharp Company, Wilmington, Del., three first-class passenger coaches, and two from Billmyer & Smalls, York, Pa., and a twenty-seven ton Baldwin locomotive for immediate delivery, and intend to have the cars running every hour between Baltimore and Towsontown within the month of October.”

Over 1,100 people invested in the enterprise, including Enoch Pratt, R. Garrett and Sons, George S. Brown, A.S. Abell and other prominent Baltimore businessmen. On August 23, 1881, the Sun reported:

“There are over 1,100 subscribers to the capital stock of the company, and the grading, masonry, depot grounds, right of way, &c., have all been done by stock subscriptions. The mortgage is light, about $13,000 on each mile of the road. The road will cost $17,500 per mile; steel rails, 40 pounds to the yard, with fine equipment, generally—Baldwin engines and first-class cars. The main depot will be on the grounds of the company, near where the first rail was laid yesterday.”[4]

The original roundhouse on the site was a frame structure. The architect or engineer who supervised the design and construction is not yet identified.

Roundhouses and railroad turntables played a critical role in the operation of steam railways. Early steam locomotives could only move forward, not in reverse, so engines and other rolling stock needed a turntable at the end of the line to turn around before returning to their point of origin. The roundhouse made a turntable even more useful by providing an enclosed or partly covered facility for storage and maintenance.

One of the earliest railroad roundhouses is a sixteen-sided structure erected in 1838 by the North Midland Railway at Derby, England. In Baltimore, the Northern Central Railroad maintained a roundhouse (built before 1876) on the eastern side of the Jones Falls where the MTA Maryland Central Light Rail Operations facility is today. In 1885, Northern Central built a roundhouse at Guilford Avenue and Preston Street – a facility lost to fire in 1911.[5] In 1875, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad built a roundhouse at the southern end of Riverside Park. In 1884, the B&O rebuilt the Mount Clare Roundhouse after an 1883 fire destroyed a similar structure on the same site. The B&O Railroad Museum occupies the historic Mount Clare Roundhouse today.

The roundhouse played a central role in organizing the lives of railroad workers from the 19th century up through the 1910s and 1920s. Some even turned the roundhouse into a metaphorical heaven supervised by the “Roundhouse Master in the Land Beyond.”[6] In June 1898, W.N. Mitchell recorded the epitaph from the tombstone of a railroad engineer buried in Richmond, Virginia that read:

“Until the brakes are turned on time,

Life throttle valve shut down;

He wakes to pilot in the crew,

That wear the Martyrs crown.

On schedule time on upper grade,

Along the homeward section,

He lands his train at God’s round-house,

The morn of resurrection.

His time all full, no wages docked;

His name on God’s pay roll,

And transportation through to Heaven

A free pass for his soul.”[7]

Baltimore & Delta Railway begin operation – 1882

By December 1881, trains began running between Baltimore and the northern edge of the city – just a few miles from Towson. The Sun described the first trip and the plans for continued development, writing:

“The first trip in a passenger coach over the Baltimore and Delta Narrow-Gauge Railroad was made yesterday evening. A passenger coach was attached to the construction train, the cars stopping within one hundred yards of Lake avenue and two and a-half miles from Towsontown. The cars attracted much attention from persons on the line of the road… Station-houses between Baltimore and Towsontown will be built at Remington crossing, Cold Spring lane, Winehurst avenue, Lake Avenue, Charles street and one near the Shepherd Asylum.”[8]

On April 17, 1882 the Baltimore & Delta Railway officially opened and celebrated with “excursion, a dinner and speechmaking.” The official train from the North Avenue station to Towson included two engines (Enoch Pratt and J.M. Dennison), one compartment car and four passenger coaches.[9] Later that year, the Baltimore & Delta merged with the Maryland Central Railroad. In 1884, the new Maryland Central Railroad completed the line through Bel Air to Delta and, despite some financial difficulties, erected a handsome passenger station at North Avenue and Oak Street in 1887. By 1889, the Maryland Central had gained control of the Pennsylvania line and began direct train service from Baltimore to York.

Baltimore and Lehigh Railway organized -1891

Just two years later, in 1891, the Maryland and Pennsylvania lines merged to form the Baltimore and Lehigh Railroad. By the 1890s, however, the decision to build a narrow gauge railway was creating new challenges. Standard gauge engines and cars, known as rolling stock, could not freely transfer to narrow gauge lines creating time-consuming and expensive transfers. The railroad also suffered from a number of accidents and accusations of negligent maintenance. On October 10, 1892, a disastrous fire hit the Falls Road roundhouse, as the Sun reported:

“A Round-House Destroyed by Fire.—The round-house of the Baltimore and Lehigh Railroad Company, on the Falls road, north of the passenger station, caught fire at 7:30 o’clock last night, and was consumed. A locomotive, which was in the house for repairs, a stationary steam engine and a lot of valuable machinery were ruined. The round-house was a frame structure two stories high and had room for eight locomotives. A room at one end of the building was used for the storage of cotton waste, and it was in this room that the fire started… The round-house burnt rapidly, and half an hour after the fire was discovered only a few charred beams and posts were left standing. The loss to the railroad company, including the locomotive, is estimated at $5,000.”[10]

Historian George Woodman Hilton observed that after the loss of four engines in the early 1890s, the Baltimore and Lehigh became, “probably the worst example of a narrow gauge that could not raise the funds to convert, but lacked enough motive power and equipment to carry the traffic it had.” Unfortunately, the arrival of the 1893 depression pushed the under capitalized company into bankruptcy.[11]

In bankruptcy, separate receivership auctions split the railroad into the York Southern Railroad (organized by Warren Walworth of Cleveland who purchased the northern end of the line) and the new Baltimore and Lehigh Railway (controlled by John Wilson Brown who helped buy the southern end of the line). Stronger financing and better prospects for carrying freight enabled Walworth to finish converting from narrow to standard gauge in 1895 when the line began to interchange freight cars with the Pennsylvania Railroad in York. More limited resources forced the Baltimore and Lehigh to continue as a narrow gauge line. The difference meant that the two railroads offered no direct connections in Pennsylvania.

Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad: 1901-1954

Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad organized – 1901

Control of the York Southern line came back to Baltimore in 1899 when Sperry, Jones & Company bought the firm. A full reunion took place in early 1901 when Alexander Brown & Company bought control of the Baltimore & Lehigh and the two firms merged into the newly formed Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad. Seven of the firm’s nine directors came from Baltimore and they named John Wilson Brown president of the line. New management meant new access to Baltimore banks to finance improvements on the line. Finally, the southern section of the line contracted with the Sanford and Brooks Company to change over to standard gauge. Thirty years later, this close relationship with the Maryland Trust Company and Mercantile Trust and Deposit Company (which served as Trustees for the company’s bonds) helped the Maryland & Pennsylvania survive the Great Depression and (unlike many smaller railroads) avoid bankruptcy.

In the early 1900s, over half the company’s revenue came from passenger service and mail delivery. The company operated two northbound and two southbound mail trains running the full length of the railroad. The company offered daily round-trip service between York and Delta, an early morning train from Delta to Baltimore (carrying car-loads of milk), and frequent local trains between Bel Air and Baltimore. At the railroad’s peak of service, Bel Air had sixteen trains a day for commuters and a late night return train for theater goers.

Many city residents took to Ma & Pa trains for weekend trips to Loch Raven or the Rocks of Deer Creek. Passenger traffic totaled about 3 million passenger miles annually, an impressive total for a railroad on which the average trip certainly did not exceed 30 miles. The trains were a central feature of life for the agricultural communities all along the line.

Freight before World War I consisted primary of agricultural goods moving to market. From some stations, such as Fallston and Woodbine, full carloads of milk shipped out daily. Wheat shipped to market from local grain elevators such as those at Bel Air and Muddy Creek Forks, and canneries at many stations including Hyde, Bynum, and High Rock were a substantial source of traffic. Despite the seasonal nature of the canning business, 12% of freight revenue in 1907 came from cannery shipments. The balance of freight originating on the line was slate from Delta and light manufactured goods from Red Lion and Dallastown. Incoming shipments were primarily coal, fertilizer, and less than carload shipments of goods to merchants along the route.

Although the railroad was showing substantial operating surpluses, it paid no dividends preferring to improve its facilities. The company purchased numerous locomotives and passenger cars to handle the booming business. They strengthened all of the bridges and trestles,installed heavier rail, and replaced the major wooden trestles between Baltimore and Bel Air with steel viaducts. New stations were built at Fallston, Baldwin, Glenarm, and Forest Hill where the original station in the Roe and Tucker General Store was destroyed by fire. Major track relocations were made between the Little Gunpowder River and Laurel Brook in Harford County and just north of Laurel on the Pennsylvania District to reduce excessive curvature.

Roundhouse built for Baltimore terminal expansion – 1910

The growth and prosperity of the new Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad required a more modern facility. In December 1905, the Sun reported on the plans:

“A siding will be placed near Baltimore which will hold 20 cars. More extensive improvements will be made south of the Standard Chain Company’s plant. The old turntable will be moved from its present location to a point several hundred yards farther west, the roundhouse will be taken away, the old workhouse and blacksmith shops will be removed and more modern structures will be erected to take their place.”[12]

By May 1906, traffic on the Maryland & Pennsylvania had grown “to an extent which makes new terminals necessary,” and they continued to plan an expanded yard on Falls road as the Sun noted:

“The company has acquired about four acres of land along the Falls road and adjacent to the tracks of the railroad. Here will be established a commodious freight yard, with sufficient tracks for the prompt handling of its business.

The yardroom of the company is now somewhat circumscribed, and provision for greater facilities has long been in contemplation. Running along the Falls road, by which throroughfare it gets an entrance into the city, track expansion was impossible without the acquisition of private lands. These have been obtained and include the stone quarry just above the company’s station and to the east of its existing tracks.

Plans for the new passenger station and for terminal warehouses to be operated in connection with additional trackage room abutting the Falls road are now under consideration.”

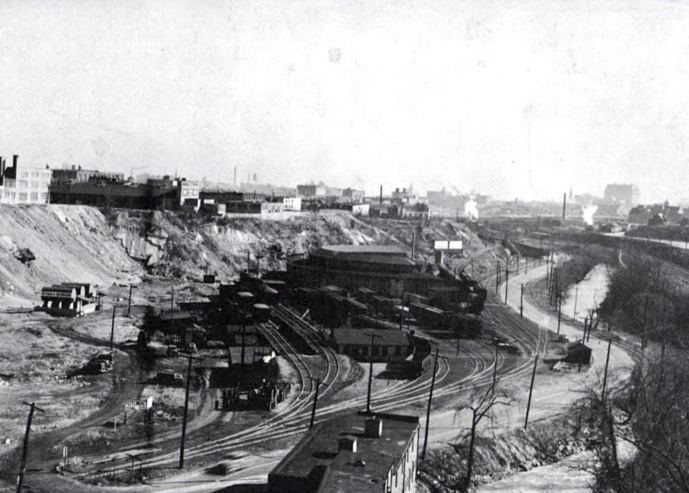

Finally in 1907 the railroad began the major expansion of its Baltimore terminal facilities building over the next few years a direct connection to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, new yard tracks, extensive coal docks, a new freight station, and the stone roundhouse.

In March 1910, the Sun reported on the construction of the Falls Road facility, writing:

“A one-story brick roundhouse and shop will be built for the Maryland Pennsylvania Railroad Company on the east side of the Falls road near Twenty-sixth street. The contract was awarded R.W. Bowers and the work will begin shortly. The structure will be of brick and concrete and will cost $25,000.”[13]

The complex cost $47,000, including new tracks, the roundhouse, the adjoining yard office and powerhouse. The yard and roundhouse were owned not by the Ma & Pa directory but by the subsidiary Maryland & Pennsylvania Terminal Company. R.W. Bowers served as the contractor and Baltimore engineer Thomas M. Ward as the designer. [14]

Thomas Ward had experience working with a variety of local railroad and civil engineering projects. In 1907, Ward worked for the Canton Railroad Company as general manager of a project connecting Canton with the Pennsylvania Railroad at Colgate Creek and a siding to the city sewerage disposal plant on Back River.[15] In 1908, Ward worked for the Ma & Pa Railroad with J.S. Norris, general manager of the Baltimore terminal, for several months “revising curves and grades on its line at Baltimore, Md.”[16]

Several references suggest that R.W. Bowers was based in Pennsylvania, appearing in a 1917 directory of members of the American Society of Refrigerating Engineers then located at 22 Fairview Avenue, Waynesboro, Pennsylvania.[17] Other accounts identify Bowers as an architect building a bungalow in Gettysburg in 1912 and another house in Reading, Pennsylvania in 1915.[18]

After its completion in 1910, the roundhouse served as the Ma & Pa’s principal shop replacing the need to maintain locomotives at the B&O Railroad’s Mount Clare facility.[19] Workers at the roundhouse maintained 16 active steam locomotives, many passenger cars, and even built many of the line’s own freight cars. As the center of the railroad’s operations, the general offices, all train dispatching, and equipment maintenance was all located in Baltimore. At its peak in 1913 the Ma & Pa had 573 employees—largely in Baltimore.

Decline and Sale of the Ma & Pa Railroad

Ma & Pa Railroad declines after WWI – 1913

After World War I, passenger traffic on the railroad began to drop quickly and, by 1936, passenger train operations made up only 10% of the railroad’s revenues. Trucks took over much of the delivery for milk and other freight and coal revenues also declined as fewer homes used coal for heating. Moving manufactured goods from Red Lion and York and slate from Delta and Whiteford became the mainstay of the railroad.

Ma & Pa offers the first railfan excursion – 1935

In 1935, the Ma & Pa pioneered a new type of railroad operation—“railfan excursions.” With the sponsorship of the Baltimore Society of Model Engineers, A. M. Bastress, traffic manager of the Ma & Pa, coordinated a trip for steam locomotive enthusiasts accompanied by company President O. H. Nance. Over the next 12 years, many more railfan excursions followed including NRHS sponsored circle trips from Philadelphia over the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Ma & Pa. These trips made the Ma & Pa one of the best-known short lines in the United States, famed around the world for the beautiful scenery and the line’s antique equipment.

Ma & Pa loses postal service contract – 1954

By the 1950s passengers had dwindled to about 12 people per train. It was clear that only the contract for operating the Railway Post Office cars was keeping the passenger trains going. In 1954, a trucking company won the contract away from the Ma & Pa, and on August 31, the last passenger train ran. Freight traffic on the Maryland District had declined to such an extent that through freight trains were no longer run. The Baltimore Sun reported on the scene at the station in Baltimore, writing:

“As the train clanked out of the station, its horn blasting, its bell ringing, a wave of nostalgia swept the passengers as the workers at the railroad’s terminal yards on Falls road stood at attention and waved their farewells to the train, making its last run after 66 years’ service.”[20]

Daily service between York and Delta was supplemented by trains as needed from Baltimore that ran only as far north as the traffic required. In 1958 the Maryland District was abandoned and the Ma & Pa moved its offices to York.

Baltimore City acquires the Ma & Pa right-of-way – 1959

In 1959, the Board of Estimates approved an ordinance to acquire the 4-mile long right-of-way belong to the Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad – from Falls Road under the North Avenue bridge up to the city line near Roland Avenue. According to the Baltimore Sun, then Baltimore City planning director Philip H. Darling suggested the “possibility of building a two-lane transit expressway along the route sometime in the future” and the planning commission “envisaged the possibility of adding the right-of-way strip to the city’s park land.” The property had originally been offered to the city for sale at $100,000 but after consideration, the city argued that the right-of-way was only worth $60,000 or less.[21] Before the purchase, the Baltimore Sun reported on the considerations that led to the development of the busway proposal for the right-of-way:

“In the past the route of the old railroad, from North avenue northward to Towson, has been recommended as the site for a rapid transit rail line and for an expressway. There were always drawbacks that killed the previous plans. The area was too sparsely settled for a rapid transit rail line, and the valley and the railroad’s right-of-way both too narrow for a regular expressway. At points the right-of-way is only 30 feet wide.”[22]

The city never acquired the full right-of-way but, in 1960, purchased the complex in 1960 for $275,000 for use as a “highway department warehouse.”

Planning begins for the Jones Falls Expressway – 1940s

Instead of a busway, the city soon started work on the Jones Falls Expressway, which followed the Jones Falls on the opposite bank from the tracks of the Ma & Pa. Planning for the highway began with the Expressway Act of 1947 and the Baltimore Master Transportation Plan of 1949. By the time it was completed, the Jones Falls Expressway grew to a length of 9 miles, seven within Baltimore City.[23]

Jones Falls Valley Plan published – 1961

In 1961, the “The Planning Council” prepared a Jones Falls Valley Plan for the Municipal Art Society and the Board of Recreation and Parks. The introduction frames their recommendations, writing:

“Few Baltimoreans have seen the treasures of nature which lie along the ten-mile Jones Falls Valley. The Valley has long been ‘hidden’ from the view of passers-by. Now, as the Jones Falls Expressway opens up the once-hidden vistas, we are confronted with a great opportunity. The concept of The Valley as a continuous urban Park—a peaceful retreat for city dwellers—has been proposed, hoped for, talked about, for sixty years. Dreams were dreamed, but translation of the vision into reality was always blocked by the lack of a detailed plan and a vivid image of what the Jones Falls Valley could become. Now here is a Plan. From it we can create a marvelous asset for all of Baltimore to enjoy.”[24]

An editorial published in the Baltimore Sun in December 1961 criticized the city’s failure to retain the right-of-way:

“…the most precious legacy a railroad has to offer is a cleared and graded path into and out of a city. This city, in fact, was urged to acquire the Ma and Pa right-of-way because it was so obvious that Baltimore some day would need such a ready-made transit route, then available for practically nothing. But the city did not have money enough to think of the future. Now we can say goodbye to the right-of-way itself. The city has relinquished any claim on a section of the Ma and Pa line near University parkway to make way for a fifteen-story apartment house. In time the right-of-way will be built over as weeds overrun an untended clearing.”[25]

Ma & Pa Roundhouse considered for streetcar museum – 1965

In November 1962, the Falls Road terminal site (including the Roundhouse) was one of three proposed locations for the construction of a new incinerator, along with a 16-acre site near Cold Spring Lane and a site in the Hampden-Woodberry area met with strong resident protests.[26]

In January 1965, Mayor Theodore McKeldin toured the Jones Falls Valley (by limousine) with the city’s director of Public Works Bernard L. Werner and Baltimore City Council president Thomas D’Alesandro III. George Kostritsky, an architect and author of the Jones Falls Valley Plan, led the group tour. As they drove past the roundhouse on Falls Road, Kostritsky told the Mayor that the site would be “an ideal place for old trolley cars” – a collection of vintage streetcars owned by the Maryland Historical Society and stored at that time on an abandoned line in Robert E. Lee Park. Bernard L. Werner quickly rejected the idea commenting, “Leave them out at Lake Roland… We need this for our central yard.” The Bureau of Highways used 18-acre site for their trucks and piles of salt but Mayor McKeldin suggested that he “liked the museum idea and believed that salt and trucks could be kept elsewhere.”[27]

In February 1965, McKeldin formally endorsed the plan’s recommendation to convert the “old Ma and Pa Railroad roundhouse on Falls road” into a trolley museum – adding that the roundhouse appeared to be “the best potential site at this time.”[28] Despite the endorsement, these plans were never implemented and when the Baltimore Sun reported on the streetcar museum move into a prefabricated building on Falls Road in 1968, the paper added:

“An early proposal had been to house the cars in an old railroad roundhouse to the north of the new museum building. But the City Department of Public Works, which uses the roundhouse to store trucks and equipment, would not give it up.”[29]

Ma & Pa Roundhouse roof collapse – 2014

The roundhouse continues in use as a truck yard and salt storage facility up through the present. Unfortunately, in 2014, after neglecting significance maintenance on the historic structure, the roundhouse building suffered a roof collapse. The Baltimore Sun, quoted Baltimore City Department of Transportation operations bureau chief Richard Hooper reflecting explaining how, “salt corroded a steel support beam, which rusted through, causing the collapse… the area was cordoned off and salt in that barn was ‘moved down a couple of barns.’”

By the time of the collapse, Baltimore DOT had already started preparations to build a new salt dome at 560 West North Avenue, a move that may have led to some neglect of the existing facility, as Hooper remarked, “[The new facility] was already planned… That’s why we didn’t put much money into that (Falls Road) building.”

Eli Pousson prepared this draft historic context on 2015 April 9. Sections of this report are adapted from a 1997 history of Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad by Craig Sansonetti published online by the Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad Preservation Society.

[1] Craig Sansonetti, “A History of the Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad,” Ma and Pa Railroad History, June 5, 1997, http://www.maandparailroad.com/mapahistory.php.

[2] Craig Sansonetti notes that the earliest actual construction along the Ma & Pa line took place between 1873 and 1876 when the Peach Bottom Railway built a narrow gauge line from York, in Pennsylvania through Red Lion and Delta to Peach Bottom on the Susquehanna River. This new line was meant to be the middle section of a larger narrow gauge railroad connecting the central Pennsylvania coal fields at East Broad Top with Philadelphia. Unfortunately, no track was ever built west of York and the railroad never bridged the Susquehanna River to connect the few miles of track on the east side to those on the west.

[3] Craig Sansonetti, “A History of the Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad.”

[4] “LOCAL MATTERS: Brief Locals,” The Sun (1837-1989), August 24, 1881, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/534576207/abstract/FE9BB8BAFCC14AE7PQ/1?accountid=10750.

[5] “THOUSANDS WATCH FiRE: Roundhouse At Guilford Avenue And Preston Street Burned LOSS ESTIMATED AT $75,000 Crossed Electric Wires Blamed For Outbreak — Ladderman Cain Is Injured,” The Sun (1837-1989), November 5, 1911, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/533961024/abstract/DFFAFDEF49B64829PQ/3?accountid=10750.

[6] B and O Magazine (Baltimore and Ohio Railroad., 1916), 56.

[7] Book of the Royal Blue, Monthly (Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company, 1897), 127.

[8] “Marietta and Cincinnati Reorganization–Other Railroad Matters of Interest: Local Briefs,” The Sun (1837-1989), December 9, 1881, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/534587518/abstract/41CAF9FFF4F94494PQ/4?accountid=10750.

[9] Reported for the Baltimore Sun, “BALTIMORE AND DELTA RAILROAD: Opening of the Narrow-Gange Steam Line to Towsontown– Junketting, Speechmaking and Jollification,” The Sun (1837-1989), April 18, 1882, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/534593827/abstract/F6AB000286684CA8PQ/1?accountid=10750.

[10] “A Fire in a Public School Building,” The Sun (1837-1989), October 11, 1892, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/535424503/abstract/169E11A1A4C947E3PQ/2?accountid=10750.

[11] Craig Sansonetti, “A History of the Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad.”

[12] “Md. And P. R. R. Plans Siding,” The Sun (1837-1989), December 9, 1905, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/537084045/citation/8F978CAC76914356PQ/3?accountid=10750.

[13] “TO BUILD 21 HOUSES: Mr. J. F. Hirt Leases Tract For That Purpose On Milton Avenue OLD POULTNEY PROPERTY SOLD Messrs. J. E. Smith, K. E. Ringer And C. W. Gardner Buy Two South Howard Street Warehouses,” The Sun (1837-1989), March 8, 1910, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/538978589/abstract/A38C52B436F34816PQ/76?accountid=10750.

[14] Edward J. Mehren, Henry Coddington Meyer, and John M. Goodell, Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer (McGraw Publishing Company, 1910), 344.

[15] Manufacturers’ Record, 1907, 62–63.

[16] Industrial Development and Manufacturers’ Record (Conway Publications., 1908), 59.

[17] Refrigerating Engineering: Including Air Conditioning (American Society of Refrigerating Engineers, 1917), 59.

[18] The American Contractor (F. W. Dodge Corporation, 1913), 78; The American Contractor (F. W. Dodge Corporation, 1915), 52.

[19] George W. Hilton, The Ma & Pa: A History of the Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad (JHU Press, 1999), 79.

[20] Robert G. Breen, “FANS WAVE, TOAST MA AND PA TRAIN: Bid Farewell During Final Run To York,” The Sun (1837-1989), September 1, 1954, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/541643430/abstract/5421F616C9B54FAEPQ/6?accountid=10750.

[21] “CITY TO SEEK MA AND PA WAY: Estimates Board Votes To Condemn Railroad Route,” The Sun (1837-1989), April 23, 1959, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/540597550/abstract/5421F616C9B54FAEPQ/4?accountid=10750.

[22] Edward C. Burks, “CITY PONDERS BUSWAY ON OLD RAIL LINE: Ma And Pa Route Is Considered For Expressway,” The Sun (1837-1989), February 1, 1959, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/539117172/abstract/1A453F5B12484862PQ/20?accountid=10750.

[23] Megan Griffith, “The Jones Falls Valley Corridor,” Treehuggingurbanist, accessed April 9, 2015, https://treehuggingurbanism.wordpress.com/2012/06/08/the-jones-falls-valley-corridor/.

[24] The Planning Council, The Jones Falls Valley Plan (Baltimore: Municipal Art Society; Board of Recreation and Parks, 1961), Baltimore Development Plans, Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Library, General Collections, https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/33521.

[25] “End of a Path,” The Sun (1837-1989), December 3, 1961, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/542461083/abstract/82E84B9B42124465PQ/3?accountid=10750.

[26] Charles V. Flowers, “BOARD SEEKS NEW SITE FOR INCINERATOR: 700 Residents Protest Proposed Hampden Area Location,” The Sun (1837-1989), November 3, 1962, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/534041379/abstract/932D1D9088024C94PQ/45?accountid=10750.

[27] Charles V. Flowers, “Board Of Estimates Tours Valley Planned For Park,” The Sun (1837-1989), January 29, 1965, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/539940097/abstract/932D1D9088024C94PQ/3?accountid=10750.

[28] “Mayor Suggests Ma And Pa Roundhouse For Trolleys,” The Sun (1837-1989), February 16, 1965, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/539984070/abstract/9A7955C381E24C57PQ/1?accountid=10750.

[29] “Architect Criticizes New Trolley Museum: Materials, Colors Called ‘Unattractive’; Park Director Defends It As ‘Very Nice,’” The Sun (1837-1989), July 1, 1968, http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/533708403/abstract/932D1D9088024C94PQ/79?accountid=10750.