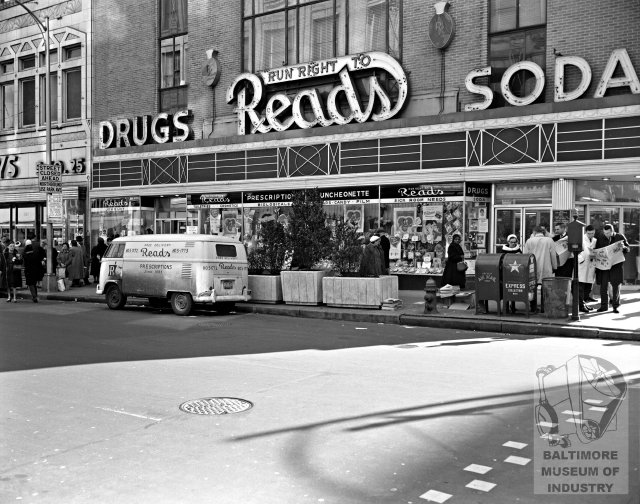

One of the West Side’s least well known but most important stories is the history of the former Read’s Drug Store at Howard and Lexington Streets and its landmark role in Baltimore’s civil rights movement. Built in 1934 by Baltimore architects Smith & May, the press heralded this Art Deco structure as a local landmark from its beginning– a modern flagship store for the Read’s chain, continuing their 50-year presence at the bustling heart of the downtown retail district.

Like many downtown commercial establishments in the early 1950s, the Read’s chain maintained a strict policy of racial segregation at their lunch counters. In 1955, a group of Morgan State students came together with the leadership of the recently organized Baltimore Committee on Racial Equality to organize a sit-in protest at the lunch counter of the Read’s Drug Store at Howard and Lexington Streets. They succeeded in this effort, marking this building as a witness to the first successful student-led sit-in protest in Baltimore and defining a powerful model for the more famous lunch-counter sit-in of Greensboro, North Carolina in 1960. This building is currently threatened with total demolition by the proposed development of the Superblock by the Baltimore Development Corporation and Lexington Square Partners. Baltimore Heritage, together with partners and supporters from across the city, is advocating for the city to reconsider this proposal and encourage the preservation and re-use of this essential landmark in Baltimore’s civil rights history.

The history of Read’s Drug Store began in April 1934 when the company announced their plan to demolish their existing building at the corner and replace it with a “modern four-story-and-basement structure” designed by the prominent firm of Smith & May, the Baltimore architectural partnership behind the iconic Bank of America Building. The press praised the new building as “the largest construction project to be undertaken in the area for some time” with a number of modern innovations in technology and design–

“A feature of the building is the provision for indirect lighting for the first floor, to which there are four large entrances. Above is a balcony containing a public service bureau and tearoom. In the basement of the building there is a restaurant and kitchen. On the third floor is located a photographic studio. Employees’ rest rooms and a large sanitary kitchen and the stock rooms of the concern are on the fourth floor.”

Back then as today, location meant everything and this corner–described as “the heart of the retail shopping district”–was key. Over the next two decades, the store remained the flagship of the Read’s chain as their business grew across Downtown Baltimore and the region.

By the early 1950s, discontent with the widespread policies of racial segregation and discrimination at Baltimore restaurants and shopping establishments began to peak, especially among the community of students and faculty at then Morgan State College who could not receive service at the Read’s Drug Store located in the nearby Northwood Shopping Center. These Morgan students joined forces with a group of white and black Baltimore civil rights activists who organized a local chapter of the Committee on Racial Equality (CORE).

First established in Chicago in 1942, CORE grew rapidly during the 1940s and 1950s, reaching over 60 local chapters by 1961. The organization of the Baltimore chapter began in 1952, with the efforts of Ben Everinghim, a history teacher at Edmondson High School, Herbert Kelman, a psychologist at the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic, attorney Robert Watts, former music teacher and founder of the interracial Fellowship House Ada Jenkins, Dr. Earl Jackson, a professor at Morgan College and the head of Morgan’s branch of the NAACP and others. After successful campaigns to desegregate the Kresge’s and Grant’s chains, CORE and Morgan students decided to combine efforts to desegregate the Read’s chain.

On January 20, 1955, Ben Everinghim the President of Baltimore CORE, Dean McQuay Kiah of Morgan State, a group of student activists from Morgan including Dr. Helena Hicks, and others staged a “sit-in” demonstration at the Read’s Howard & Lexington location at the same time as another group of Morgan students staged a full week of demonstrations at the Read’s store at the Northwood Shopping Center. Their brave efforts yielded remarkable results with the quick response accounted in the Baltimore Afro American by B.M. Phillips as “A True Story,” describing a conversation between Morgan State College Dean George Grant and an unnamed “Read’s Drugstore official,”

Read’s official: Please call your students off. They’re staging a showdown here in our Northwood store. We’re losing business.

Dean Grant: We teach our students here they must practice democracy and help others to understand it. I don’t think you want us to tell them what they’re doing is wrong.

RO: Yes, but we’re losing business with them sitting at our counters.

DG: Well, there are several things you can do.

RO: What’s that?

DG: Why not put a sign up in your store saying dogs, cats and colored people are not allowed?

RO: Well, we couldn’t do that.

DG: Well, why not put an ad in the AFRO saying that Read’s wants colored people to shop there but they can’t eat there; and you know you have another alternative, you can say to all your customers everyone can be served at our lunch counters.

RO: Well, we are in sympathy with this thing – we’ll see what can be done.

After only another two hours of delay the Read’s official called back to declare that the Read’s Drug Store decided to desegregate the On January 22, 1955, a front page headline on the Afro American of read, “Now serve all,” and included the announcement by Read’s Drug Stores President Arthur Nattans Sr.,

“We will serve all customers throughout our entire stores, including the fountains, and this becomes effective immediately.”

This building is a witness to an incredible event in Baltimore’s civil rights history and should be preserved as a continuing part of a vital neighborhood on the Downtown’s West Side. Please share your own knowledge and recollections of the civil rights heritage that can be found in the histories of West Side buildings and places.