Jim Dilts, a former Baltimore Heritage board member and longtime advocate for local history and architecture, passed away on Tuesday, May 8. Jim had an enormous influence on his adopted hometown of Baltimore. In his quiet way, he helped many of us learn about and appreciate the art and architecture around us. There have been lovely tributes to Jim over the last few days, notably by fellow journalist Mark Reutter and former Baltimore Heritage board president Fred B. Shoken.

In his interview this winter, Jim talked about everything from fighting highway plans to creating movies about Broadway tap dancers. As you’ll discover in the excerpts below, Jim’s intellect, understanding, and sheer joy in living, working, fighting, and just being part of our city clearly come through. He will be missed.

On how he started covering urban issues for his Baltimore Sun column “The Changing City”:

“[In the late 1960s] there was a great interest in urban studies, they were called. People don’t talk about that any more, that term. All these books were being written by people talking about how everybody was moving to the city. That was then, urban areas, not necessarily within the city, but urban areas… I think the Ford Foundation sponsored this seminar, whatever you want to call it, at Northwestern, which is where I went to school. So I got my editor at the Sunday Sun to send me to this thing. It was three months or something like that… We listened to all of these urban experts, and again went around Chicago and looked at things. So then when I came back, I decided I ought to do something, since they had paid for it. So I started this column called ‘The Changing City.’”

On covering and fighting against highways in Fell’s Point and West Baltimore:

“Jane Jacobs inspired me because she got me interested in these highways. And a lot of the stuff I wrote in “The Changing City” column was about expressways, and that was when the road was going through Fell’s Point. It was going through Leakin Park, it was going through West Baltimore. It was coming to the Franklin-Mulberry corridor and through downtown and through Fell’s Point. Tom Ward and Lu Fisher and a lot of other people were involved in the fight in Fells Point.”

But, you know, if you’re going to run [a highway] through the middle of a neighborhood, there’s not much mitigation you can do. I mean, you demolish our houses and put a multi-laned highway through there.

There were a lot of interesting groups involved in this fight, the expressway fight. I used to call them the Urban Mafia. We would meet in church basements and stuff like that. There were guys… from CORE, the archdiocese, from a lot of different groups, and they would know different things, and we would all trade secrets and stuff like that, and then I would write about it. I tell you, when I was writing these articles about the expressway in Baltimore, I was around there until like 2:00, 3:00 in the morning, writing this stuff. I was on fire. I was on fire. There was nothing like it.”

On writing books about Baltimore architecture:

“Well, you know, everybody thinks that, in your profession, if you’re a teacher, you think education is the answer. If you’re a health worker, you think better health is the way to solve society’s problems. And they’re all right, you know. If you’re a writer, you think, well, you know, put it down, and at some point, it’s going to be useful to somebody. So I’m a writer. I was very happy to be able to do these books. I talked about the guide to Baltimore architecture. And then the next one was Baltimore’s Cast Iron Buildings. I did it with Kitty Black, who is really a wonderful person… she was the person who really sort of had my back and was a support for this project.”

On the tap dance film “Jazz Hoofer”:

“One of the people who was considered the greatest tap dancer produced by the modern jazz movement was from Baltimore. His name was Baby Laurence. He was in Baltimore, and he was not doing well because there wasn’t a great market for tap dancers at the time. This was in the sixties. You know, for a while on Broadway, every Broadway musical had a tap dancer …Then when Agnes de Mille did Oklahoma, that was the end of that—that was ballet, and that was the end of this tap dance routine in these Broadway musicals… So these guys were essentially out of work.

Baby Laurence, all he’d ever done since he was a child was sing and be in show business and be a tap dancer. He called me up at the paper and sort of announced his presence in Baltimore and the fact that he wasn’t doing too well, and maybe I’d like to do something about it. I said okay.

We met, and at that time, the Left Bank Jazz Society was going big in Baltimore. They gave us some gigs where he could dance. I think this was the only time this ever happened to me, but I despaired of being able to describe in words what he was doing with his feet. I just could not do it. It was way beyond me. So I thought the only way we’re going to do this is we’ve got to make a film of him. So that’s what we did.”

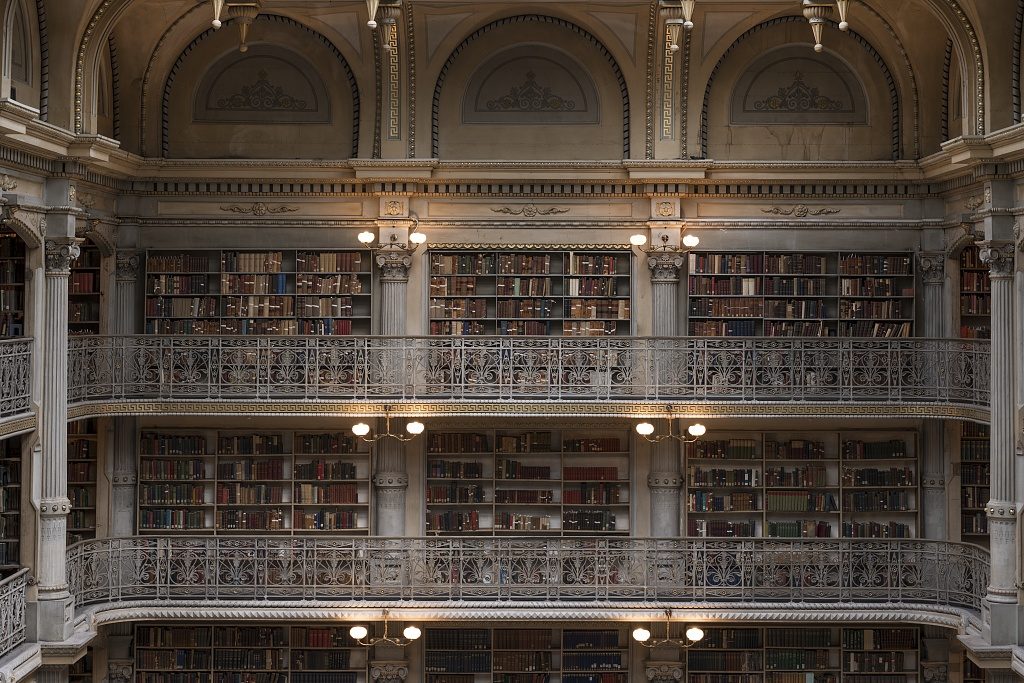

On working to reopen the Peale Museum:

“[My involvement] started with the history of the Peale Museum itself [and] is long and involved. The history of the restoration effort is somewhat knotty. But we’ve been at this for about ten years now, and my own feeling was that the building was empty. It was not being used. It was the city’s municipal museum and that something should be done with it. That was my motivation.

[About] five years ago, we re-organized legally as the Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture. The city owns the building. We got a dollar-a-year lease, a long-term lease from the city with the proviso that we restore the building within a certain amount of time.

So we’re about, I guess, halfway through [renovations] now. The goal is to reopen by 2020. The construction is going on now in the building. There’s a new roof on it, and the exterior, all the doors and windows and so forth, which had been falling apart are now being restored.

So our mission now in my mind is to—we want to reinvent the urban museum of the twenty-first century, and this is difficult. We have to combine, find a way to relate the two-hundred-year history of the building and make this accessible to people in the digital age who are now not using these things and not picking up a book so much and not so much looking at traditional museum exhibits.”