Today, Station North is well-known for its growing importance as a home for artists, musicians and designers. In recent years, former factories have been transformed into schools and artist studios. The exciting progress of this neighborhood’s renewal and revitalization is based on a rich history and a tremendous collection of local landmarks that have long made North Avenue an important destination for Baltimore residents. Explore the history of Station North through our Explore Baltimore Heritage tour or read on for a brief introduction to how Central Baltimore and grown and changed over the past 200 years.

Country Homes on Boundary Avenue & York Road

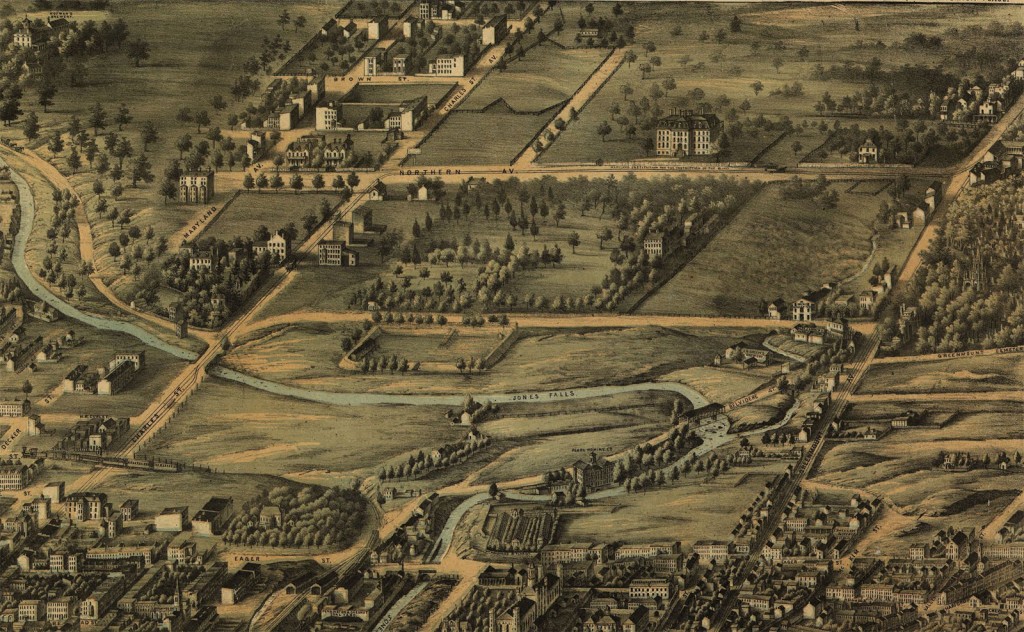

At the beginning of the 19th century, the hilly landscape north of the Baltimore harbor was a place for the large country homes and estates that reflected the wealth of the growing city and offered their owners a retreat from the yellow fever epidemics that still regularly swept through the crowded blocks in Fell’s Point and Jonestown. In the neighborhood of Mount Vernon, south of the Jones Falls, stood Belvedere, the home of John Eager Howard. Where Green Mount Cemetery is located today was the home of Robert Oliver; next door was his neighbor and business partner John Salmon adjoining the rocky banks of the Jones Falls.

The growth of the city to the north started slowly when, in 1787, Baltimore County established a series of new public turnpikes to connect what was then known as Baltimore Town to nearby Reisterstown, Frederick, Maryland and York, Pennsylvania.Road construction started with convict labor but after the Baltimore and York-town Turnpike incorporated in 1805. After raising $100,000, the company started construction in 1808 on York Road (today’s Greenmount Avenue). In 1844, genteel carriages and farmer’s wagons were joined by one of the city’s earliest transit services when an omnibus started regular service between Monument Square in downtown Baltimore and the Coldspring Hotel in the suburban community of Govanstown. In 1858, the Baltimore and Yorktown Turnpike Railway incorporated and started to lay track in 1863 and the first cars reached of Govanstown on July 16, 1863.

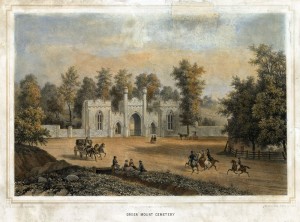

New roads and new transit in the 1840s and 1850s helped turn the generation who inherited these aging country estates into enterprising developers as former farms were subdivided and sold off to wealthy locals and speculative builders. One local tobacco merchant, inspired by the example of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Connecticut led a successful campaign to turn Robert Oliver’s country estate into Green Mount Cemetery (dedicated in 1839).

In the years after the Civil War, the area developed into a suburb of Baltimore as one early resident at 323 East North Avenue reflected the Baltimore Sun in 1958, commenting:

“That was back in the ’80’s! when the few people who lived along Boundary Avenue, as North was called then, were considered suburbanites…for not only was the neighborhood far from civilization. It had a distinct off-the-beaten-path atmosphere….We moved across the line, occupying a large house (323) in the 300 block. It was one of the only group of houses on the south side between Calvert and Greenmount, and even then all of the houses in the block were empty save the one in which lived a Dr. White.”

Railroad Yards & Streetcar Suburbs

Transportation continued to play an essential role in the development of the area as it approached the end of the 19th century and entered the 20th century. The completion of the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel in 1873 (connecting Baltimore to DC by railroad) spurred new industrial development.

The Crown Cork & Seal Company moved to North Street (now Guilford Avenue) in 1897 and is today better known as the complex of buildings including the Copycat, the Cork Factory and the new Baltimore Design School. The McShane Bell Foundry, established in 1856, also moved to the area in the 1890s. The new North Avenue Bridge (built 1895) carried North Avenue high over the Jones Falls and the railroad tracks in 1895. In 1914, new bridges spanned the CSX railroad tracks north of 25th Street on Guilford Avenue, Barclay Street and Greenmount Avenue.

The Crown Cork & Seal Company moved to North Street (now Guilford Avenue) in 1897 and is today better known as the complex of buildings including the Copycat, the Cork Factory and the new Baltimore Design School. The McShane Bell Foundry, established in 1856, also moved to the area in the 1890s. The new North Avenue Bridge (built 1895) carried North Avenue high over the Jones Falls and the railroad tracks in 1895. In 1914, new bridges spanned the CSX railroad tracks north of 25th Street on Guilford Avenue, Barclay Street and Greenmount Avenue.

By the 1890s, the extension of electric streetcar service north of the Jones Falls supported the development of handsome blocks of three-story rowhouses on Charles, St. Paul, and Calvert Streets. While most residents moved into one of the three-story marble trimmed rowhouses a few might have preferred apartment living at The Walbert (1907) or in similar apartment buildings developed along Charles Street or Mount Royal Avenue.

New residents needed new schools and new churches. Wealthy churches like Lovely Lane Methodist Church (1880) led a migration out of downtown, followed by more congregations including St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church (1898) and the Seventh Baptist Church (1904). In 1890, Public School No. 32 was built for for white students at Guilford Avenue and Lanvale Street. Black children attended Benjamin Banneker Elementary School (historically known as Colored School No. 113) just a few blocks east at Federal Street and Greenmount Avenue built 1895. The latter school was expanded in 1931 and closed in 1984. The original building was demolished but the 1931 addition has been reused.

As the neighborhood grew, the aging brick Union Station seemed a poor gateway for the city. In 1911, a new Beaux Arts design for Penn Station created an enduring icon in Central Baltimore.

Auto Showrooms & Segregation

In the early to mid 20th century, the residential character the streetcar suburbs around North Avenue began to change as the suburban growth moved even farther north to neighborhoods like Roland Park and Guilford. As Baltimore increasingly got around by automobile rather than streetcar, the city changed to suit the needs of these new drivers. Showrooms, dealerships and garages popped up on Mount Royal and Howard Street. New steel bridges spanned the Jones Falls, including the Guilford Avenue Bridge (1930, rehabilitated 1990) and the Howard Street Bridge (1939). North Avenue Market (1928) followed a modern design that made it a prototype for new automobile-oriented strip malls.