The buildings and people of Harlem Park tell stories of architecture and community over 150 years of history like few other neighborhoods in Baltimore. The earliest stories reveal the origin of the neighborhood as “Haarlem” – a pastoral country estate – followed by its growth as a wealthy west side suburb. In the early twentieth century, the area transformed into a spiritual and cultural center for West Baltimore’s African-American community. Across the decades, builders, residents and religious leaders left a legacy of unique landmarks including Lafayette Square, the former Harlem Theater, a wealth of magnificent churches and grand brick rowhouses. These buildings still stand as monuments to the generations of people who built Harlem Park, and they remain important assets as community leaders continue to build a stronger future for the neighborhood.

Join us in exploring the history of Harlem Park and Lafayette Square through its landmarks and its people. Learn more about people and places of West Baltimore’s Red Line neighborhoods.

1760s-1860s: Farming to Fortifications at “Haarlem”

The name Harlem comes from Dutch merchant Adrian Valeck who arrived in Baltimore soon after the end of the Revolutionary War. Established outside the city in the late 1700s, Valeck’s Haarlem estate featured an expansive garden of flowers and fruit trees imported from the finest nurseries in Europe. In the early 19th century, Dr. Thomas Edmondson took over the property and kept up the garden, sharing his expertise as president of the Maryland Horticultural Society. In 1857, a group of nearby property-owners donated land to the city to establish Lafayette Square, a new public park just a few blocks northwest of Edmondson’s home. The success of development around Mount Vernon Place and Franklin Square encouraged local property-owners to place parks at the center of any new suburban development. Their effort came to a quick stop, however, when the Union Army occupied the city and built a hospital and camp on Lafayette Square in 1861. But as soon as the troops departed in 1865, the effort to turn the landscaped garden into a blossoming suburb began again.

Dr. Thomas Edmondson (1808-1856)

Born in 1808, Dr. Thomas Edmondson was the son of a prosperous local merchant. He graduated from the University of Maryland medical school in 1834 but never practiced as a doctor. Edmondson collected artwork and purchased paintings from local artists like Alfred Jacob Miller, Richard Caton Woodville, and Ernst Fischer (works that can still be found today at the Maryland Historical Society and Baltimore Museum of Art). A decade after Edmondson’s death, his heirs donated a portion of his estate to Baltimore to form Harlem Square in 1867. In 1871, the city passed a resolution to take Thompson Street and rename the street “Edmondson Avenue.” The name remains a lasting reminder of one of the neighborhood’s earliest residents.

West Baltimore and the Civil War

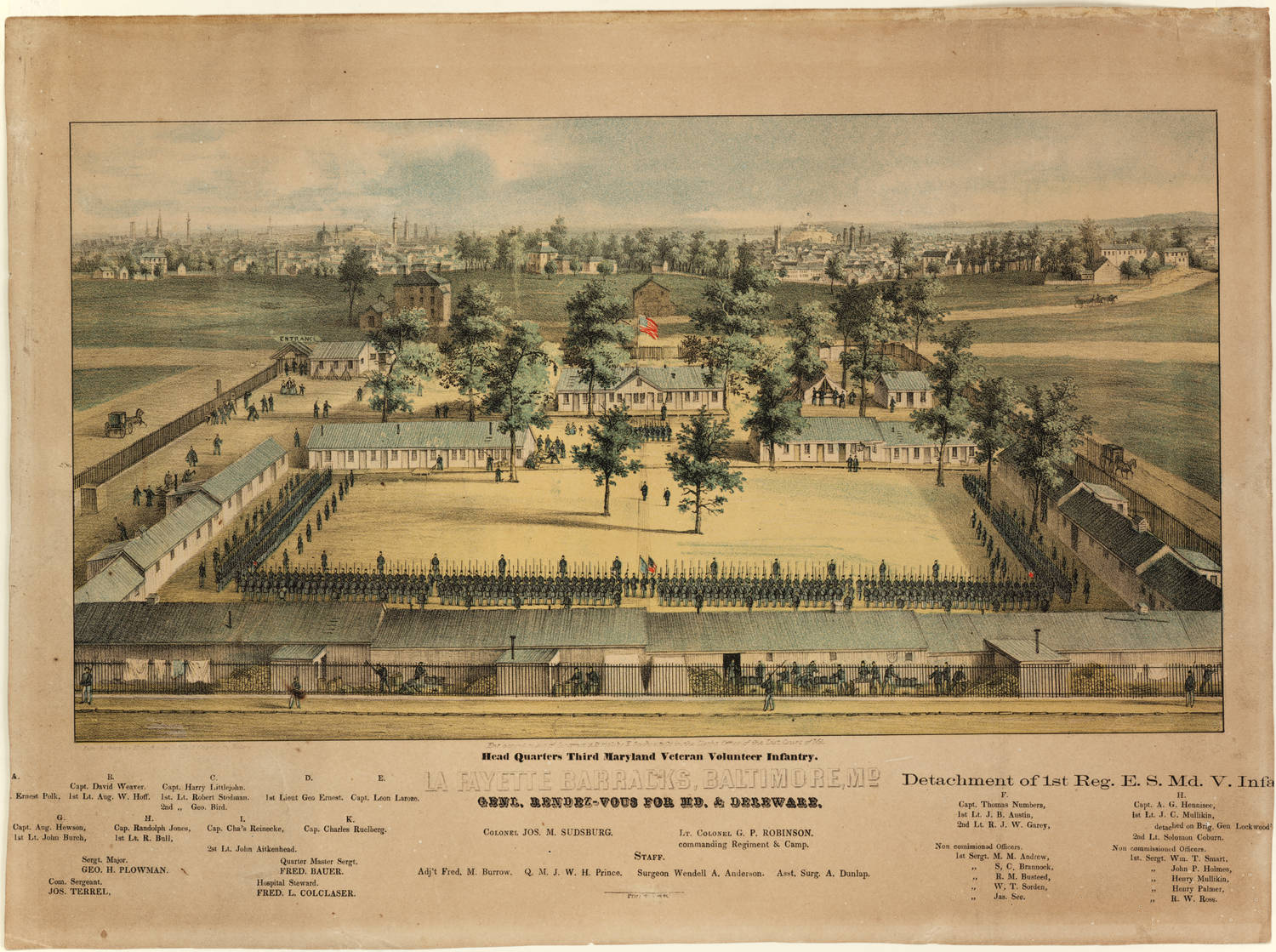

Soon after the Civil War began Union troops arrived in force and built up a ring of fortifications, camps and hospitals around the city. Lafayette Square became Lafayette Barracks, an encampment “filled with ugly wooden sheds [and] swarming with rough troops” according to 19th century historian John Thomas Scharf, who moved to Lafayette Square after the war.

After bloody battles in Antietam and Gettysburg, Union soldiers from New York and Pennsylvania spent weeks recovering from their injuries at Lafayette Barracks and Hicks U.S. General Hospital just east of Harlem Park. Union camps in West Baltimore also played a role in the unravelling of slavery as enslaved blacks escaping from bondage found shelter among the northern troops during the early years of the war. Local free blacks built earthworks for the Union Army (including Fort No. 1½ near today’s Bon Secours Hospital) to protect against a Confederate attack. In 1864, hundreds of formerly enslaved men came to Baltimore to join the Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment organized at Birney Barracks in today’s Druid Hill Park.

1860s-1920s: New Homes in Harlem Park

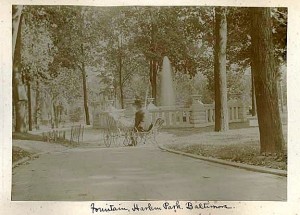

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the city swelled in size and entrepreneurial builders in West Baltimore doubled their early development efforts. In Lafayette Square, the city replanted trees and flowers and rebuilt winding walks. West Baltimore’s parks became attractive destinations for wealthy residents seeking a breath of fresh air and an escape from Baltimore’s crowded downtown. Dedicated in 1876, Harlem Square brought even more new residents to the area. In the 1870s and 1880s, developer Joseph Cone erected hundreds of rowhouses in the blocks around Harlem Park. These new homes featured stylized cornices with jigsaw-cut patterns of sunflowers, butterflies and Japanese fans. New amenities like gas lighting, hot water, and door bells attracted buyers, including many German-speaking factory owners and shop-keepers from Baltimore’s growing middle-class.

Lafayette Square to Church Square

Lafayette Square has often been called Church Square for the unrivaled number of churches located around the park. In 1869, the Lafayette Square Association enticed the Episcopal Church of the Ascension to move to a lot on the northeast corner of the park. Ascension’s Reverend Calloway argued “the church should lead rather than follow the population” into the city’s fashionable new neighborhoods. Grace Methodist Episcopal Church began work on a new church on the south side of the square in 1871. Bishop Cummins Memorial completed a new church on the west side of the Square in 1878 followed by Lafayette Square Presbyterian in 1879. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, these white congregations sold their buildings to African-American congregations. Metropolitan United Methodist Church was the first to move—leading a ceremonial march from their old church on Orchard Street to their new church at Lafayette Square in 1928. St. John’s A.M.E. moved from Lexington Street in 1929, St. James Episcopal in 1932, and Emmanuel Christian Community moved from Calhoun Street in 1934.

The “Park” in Harlem Park

“As soon as the services were over the people, the ladies brilliantly dressed and the men wearing their go-to-church clothes, marched along the winding paths of [Harlem Park] in a steady stream.” – Baltimore Sun, March 1910

At nearly ten acres, Harlem Park was more than double the size of nearby Lafayette Square or Franklin Square a few blocks south. The artfully designed landscape offered colorful beds of flowers shaped like diamonds, hearts, stars and crosses. New houses around the park also attracted new churches. In 1877, the Central Methodist Episcopal Church South was built at Stricker Street and Edmondson Avenue (now Unity United Methodist Church). In 1880, the Harlem Park Methodist Episcopal Church moved to Gilmor Street on the west side of the park.

“The little ladylike Squares… it was as if the virtuous dames had drawn together round a large green table, albeit to no more riotous end than that each should sit before her individual game of patience” – Henry James, 1906

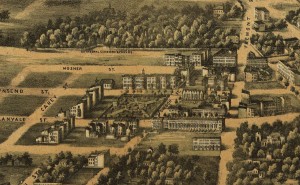

New schools kept pace with new churches. In 1875, the Maryland Normal School (an institution for training teachers that later became Towson University) moved to the northwest corner of Lafayette Square. In 1881, the Maryland School for the Blind opened at Edmondson and Fulton Avenues. The same building housed Morgan State University before the school moved to northeast Baltimore in 1917. In 1892, Grammar School No. 18 opened at the corner of Harlem and Monroe Streets.

1920s-1940s: A Changing Community

In the early 1900s, residents in Harlem Park fought to exclude African-Americans by imposing deed restrictions on local property-owners and harassing black households who tried to buy homes around the park. By the 1920s, however, the city’s growing black middle-class successfully gained access to more desirable properties in Harlem Park. Many of the area’s white residents moved away to newer suburban communities like Rognel Heights and Walbrook. By the early 1930s, the neighborhood was largely African-American. Black doctors and lawyers in grand houses lived alongside working-class tenants in boarding houses and smaller alley houses. Harlem Park became an integral part of a black community that grew to include homes, churches and businesses from North Avenue to Franklin Street and Eutaw Place to Fulton Avenue.

Harlem Theatre Makes a Marquee Attraction

As in Lafayette Square, white congregations began moving away from Harlem Park in the late 1920s. In 1925, the Harlem Park Methodist Episcopal Church moved eight blocks west and, in 1930, the former church was converted to the Harlem Theatre. In its heyday as a premier movie house for West Baltimore’s black residents, the Harlem boasted a 65-foot marquee with 900 50-watt light bulbs and a forty-foot high sign that could be seen from two miles away. The opening weekend in October 1932 drew crowds of over 5,000 people. Once inside, movie-goers could look up to enjoy twinkling electrical stars and projected clouds that floated overhead. The theater closed in the mid-1970s and returned to use as a sanctuary for the Harlem Park Community Baptist Church.

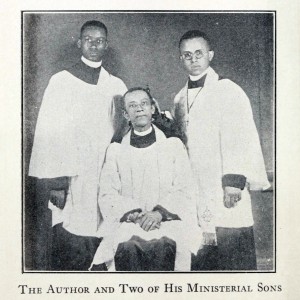

Rev. George Freeman Bragg, Jr. and St. James’ Episcopal Church

Rev. George Francis Bragg (1863-1940) may be little-known today but he served as pastor of St. James Church for over 40 years. His visionary leadership of St. James is matched by his legacy as a co-founder of the Afro-American newspaper, a historian and a political advocate. His life and work reflected the growing strength of Baltimore’s black community in the early 1900s. Born on January 25, 1863 in North Carolina, Bragg’s early years were shaped by the Civil War and Reconstruction. Ordained as a deacon in Virginia in 1887, Bragg entered the priesthood in 1888 and arrived in Baltimore in 1891 with a passion for fostering independent leadership within the black church. He joined the 66-year old St. James’ Church that was then located downtown at Saratoga Street and Guilford Avenue.

In 1901, Bragg led his church to a new building in northwest Baltimore at Park Avenue and Preston Street. When middle-class African-Americans in his congregation continued to move even farther west, Bragg moved St. James again to Lafayette Square in 1932 where they celebrated their first service on Easter morning. Rev. Bragg lived on the Square and remained active in the city’s political and civic life up until his death in 1940.

1930s – 1950s: Harlem Park and Old West Baltimore

Harlem Park provided a foundation of stability and a strong sense of community that helped to shape the activism and leadership of Baltimore’s black community during the middle of the 20th century. At the same time, local residents grappled with discrimination in employment, education and housing, including the Federal Housing Administration policy of discouraging lending in Harlem Park and other black neighborhoods through “red-lining.” Many of the people who grew up in Harlem Park during this period dedicated themselves to combating discrimination and trying to improve conditions for themselves and their neighbors. These early leaders included Mrs. Violet Hill Whyte in local policing and juvenile justice, Parren and Clarence Mitchell in civil rights and politics, and Dr. Eugenie Phillips in community health.

Mrs. Violet Hill Whyte (1897-1980) – 625 N. Carrollton Avenue

On December 3, 1937, the Baltimore City Police Department assigned Mrs. Violet Whyte to the Northwestern District making Whyte the city’s first black police officer. 40 years old, a former teacher, and a mother with 4 children, Whyte was not a typical officer, but she earned the nickname “Lady Law” for putting in countless 16-hour days over a 30 year career. Whyte had deep roots in the community as the daughter of Rev. Daniel G. Hill, a prominent pastor at Bethel AME Church, and a graduate of Douglass High School and Coppin State College. Together with her husband George, a Baltimore school principal, Whyte lived at 625 N. Carrollton Avenue. Whyte refused to carry a gun and was passionate about her work for the protection of children and her concern for juvenile offenders.

Clarence Mitchell (1911-1984) and Parren Mitchell (1922-2007) – 712 N. Carrollton Avenue

Born and raised on Carrollton Street in Harlem Park, Clarence and Parren Mitchell took on the challenge of fighting for civil rights well beyond their own community. As a young reporter for The Afro-American, Clarence covered the story of a 1933 lynching on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and came back to Baltimore transformed into an activist. He became the NAACP’s chief lobbyist on Capitol Hill and was known as the “101st Senator” for his hard-won influence. Parren was the first black graduate of the University of Maryland School of Law and taught at Morgan State University. Elected as the first black member of Congress from any Southern state since Reconstruction, Parren helped to found the Congressional Black Caucus.

Dr. Eugenie Phillips (1918-2010) – 1612 Edmondson Avenue

For nearly 50 years, Dr. Eugenie Phillips worked as an obstetrician-gynecologist for families in Harlem Park and across West Baltimore. A New York native, Dr. Phillips moved to Baltimore in the 1940s where she married Dr. Townsend Woodward Anderson in 1946. They turned their handsome three-story Edmondson Avenue rowhouse into a home for their private practice and worked at Provident Hospital. Her neighbors made sure no one except Dr. Phillips or her husband parked a car in front of their house so that they could always find a spot after returning home from caring for local mothers and children.

1940s-1970s: Urban Renewal, Rehabilitation and Demolition

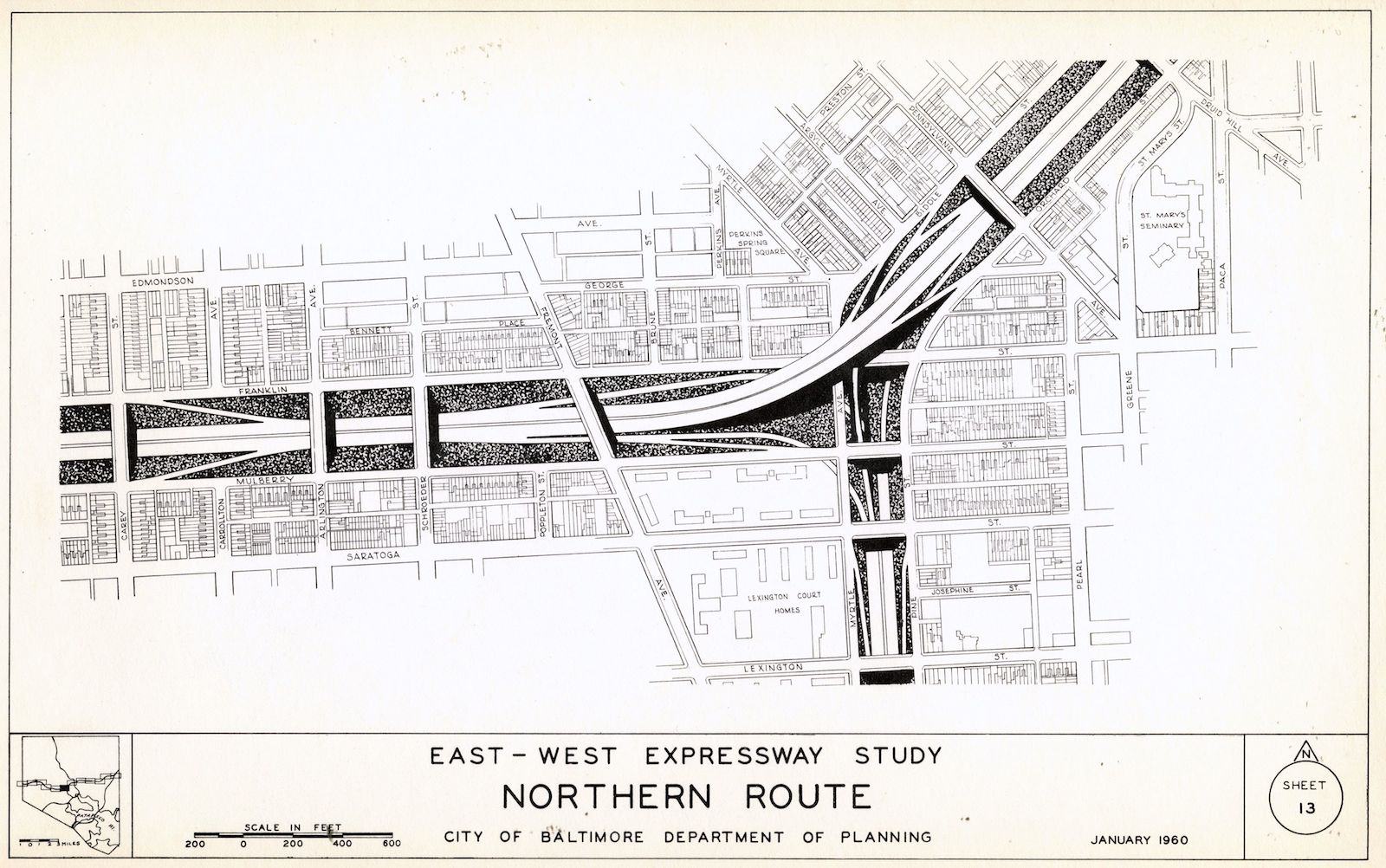

Many of Baltimore’s older communities faced new challenges in the decade after the end of World War II. In Harlem Park, concern over overcrowded and deteriorating housing sparked a controversial program of “urban renewal” that mixed social programs, demolition and rehabilitation projects, a new school and new housing over a twelve-block area. The rise of the automobile made more dramatic changes as city streets in the area converted from two-way to one-way and the city demolished scores of homes south of Franklin Street for the development of the East-West Expressway. The inner block parks and the Harlem Park Elementary Middle School are both legacies from this period of change.

Electric Streetcars to the Highway to Nowhere

Baltimore’s extensive streetcar network tied Harlem Park to neighborhoods across the city with regular service along Edmondson Avenue. But in the 1940s, fast growing suburbs and an increasing number of drivers inspired city planners to push for the construction of an “East-West Expressway” through Harlem Park and neighborhoods all along Franklin Street. West Baltimore residents responded by organizing the Relocation Action Movement, and joined with anti-highway activists from East Baltimore to form the Movement Against Destruction. In the late 1960s, despite growing opposition, the city demolished over a dozen blocks of homes and businesses between downtown to the present day site of the West Baltimore MARC Station.

In the early 1970s, highway officials built a nearly two-mile long segment of the planned highway but mounting protests finally forced the city to abandon efforts to continue construction through Greater Rosemont and Leakin Park. The one-mile stretch of expressway that was completed with such controversy and such cost (economic as well as social) was being called “The Road to Nowhere.” Fortunately, the Red Line route will use the highway right of way to reconnect this stretch of West Baltimore back to the city.

Harlem Park Elementary/Middle School

Built in the early 1960s, the Harlem Park Elementary/Middle School was controversial throughout its planning and construction. Initial efforts to locate the school within Harlem Park met with stiff resistance by the NAACP and others defending the park as one of only a few green spaces in the city’s segregated black neighborhoods. The school site shifted to require the the condemnation of three full blocks of homes located immediately north of the park. The $5,300,000 school complex, designed by architects Taylor & Fisher, still ultimately took half the park for recreational fields.

Alley Houses to Inner Block Parks

One of the most ambitious elements of the urban renewal plan for Harlem Park was the city’s goal of demolishing the hundreds of four and five-room houses on Woodyear Street, Vincent Street and other back alleys. Decades of neglect created difficult conditions for tenants. Some houses still lacked indoor toilets or other plumbing facilities. The neighborhood’s urban renewal plan (adopted in 1961) envisioned replacing these homes with 29 small parks and playgrounds. Demolition started in the 1960s, requiring the relocation of hundreds of local residents, but development of the parks proceeded slowly. Debate over which city agency should maintain the parks contributed to their disuse. Neighborhood residents also reflected that the culture of socializing on the front steps of Baltimore rowhouses conflicted with the isolated location of the parks at the backs of houses.

1960s – 2000s: Organizing and Activism

Over the last 30 years, Harlem Park has struggled with job loss, poverty, and vacant housing. As with the generation before, neighborhood residents faced these challenges with courage and creativity. The historic Sellers Mansion at 801 N. Arlington Avenue was converted into the headquarters for an innovative recreational program in the 1960s. Local churches helped build more affordable senior housing including St. James Terrace Apartments in 1960 and N.M. Carroll Manor in 1978. Activists won support for new community services with the Lafayette Square Center opened in 1974 at Lafayette Avenue and Gilmor Street. Residents today continue to work with city leaders and partners to preserve Harlem Park’s rich history and build a bright future.

Harlem Park Neighborhood Council & the Lafayette Square Association

For decades, community activists have organized residents in Harlem Park and Lafayette Square to advocate for improved public safety, housing and health. Among the hundreds who have supported the neighborhood through the years, a few examples illustrate the different roles local residents played. G. Brook Dozier organized the “Willing Workers Organization,” a Harlem Park block club, in 1955 and continued to teach at Harlem Park Middle School for nearly 30 years. Madeline “Mae” Pullen (resident of 702 Carrollton Avenue) helped to organize the Harlem Park-Lafayette Square Community Association and was remembered by Mayor Kurt Schmoke as the “Mayor” of Harlem Park. Barbara C. Ferguson (resident of 842 N. Carey Street) grew up in the neighborhood and moved back in 1974. Ferguson started her career as a social worker and applied her passion for her community to help found Pius V Housing. Carmena F. Watson (resident of 1103 Harlem Avenue) worked alongside Ferguson and Pullen, and other members of the Harlem Park Neighborhood Council and the Lafayette Square Association. In 1996, Watson succeeded Congressman Elijah Cummings to represent the 44th District in the Maryland House of Delegates.

Operation CHAMP

“I have never seen such abundant, unchanneled, hungry talent. The kids want to learn everything and anything.” Olympic swimmer Donna de Varona, 1966

From the 1960s through the 1980s, Operation Champ offered some of the only recreational programs available to black youth living in West Baltimore neighborhoods. The federally funded program took Olympic and professional athletes into low-income communities in sixteen cities across the United States, including Detroit, Chicago, and Baltimore. Players from the Baltimore Bullets basketball team were employed to teach basketball. Even after federal funding ceased, the city and residents raised funds to continue to program. Operation CHAMP opened on Lafayette Square located in the Sellers Mansion and operated three “mobile units” delivering games and playground equipment of all sorts to neighborhoods across the city. These trucks took over city streets and turned them into pop-up playgrounds for a day.